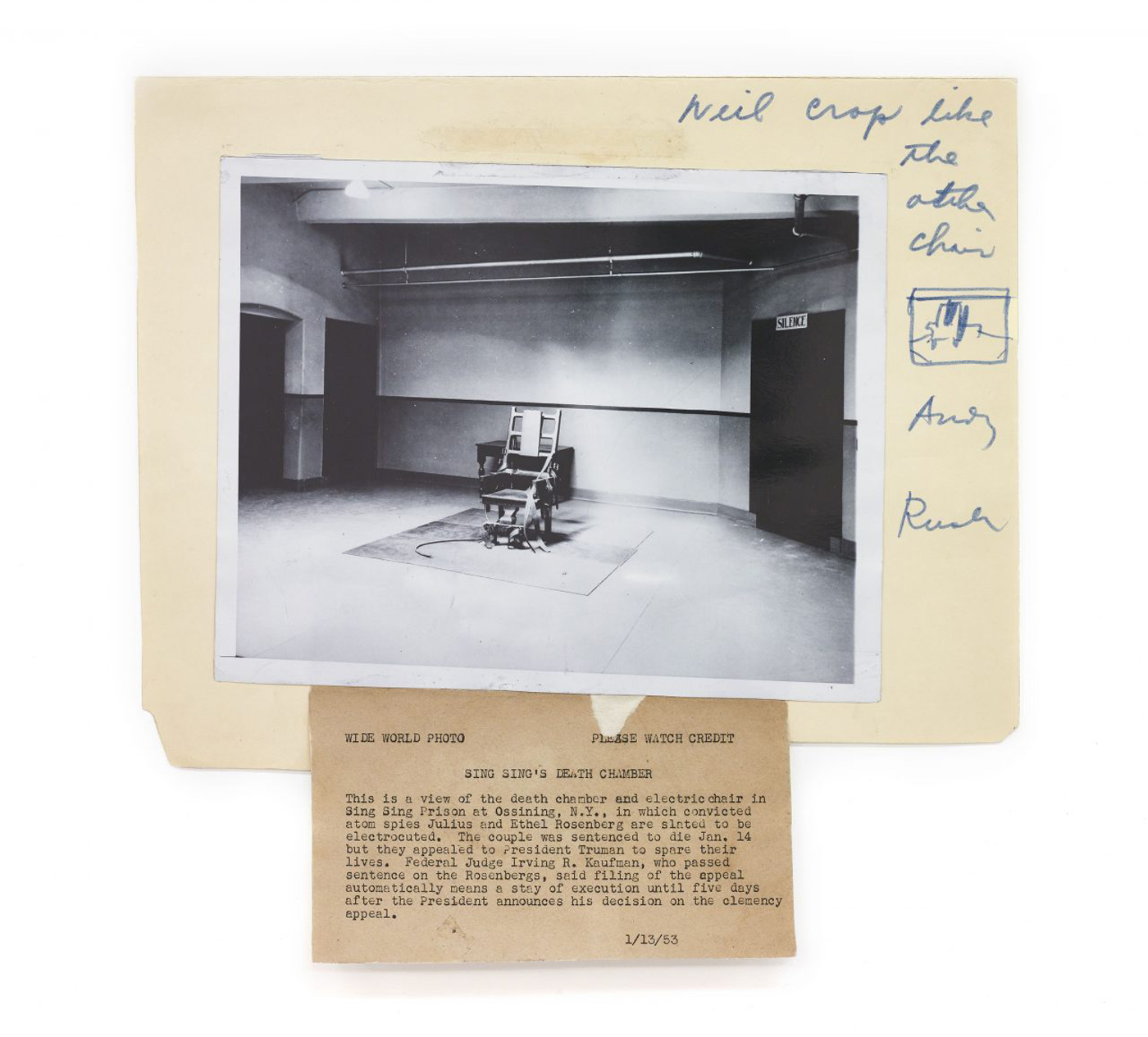

So, what links the icon of pop art, the atom spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and an almost-forgotten murderer named John Paonessa? Simple, the electric chair. Warhol used this image to create a series of coloured screenprints. Part of his recurring fascination with life’s dark side, Old Sparky was as famous as Warhol long before the artist himself was even born.

By Warhol’s birth on August 6, 1928 it had been in operation since August 6, 1890, debuting with the execution of murderer William Kemmler. Warhol was born on the 38th anniversary of Kemmler’s horrifically botched execution, during which Kemmler was partly cooked and set on fire. Only four days before Warhol’s birth, murderer Ludwig Lie had died in the chair.

A mere three days after his birth murderers George Appel, Daniel Graham and Alexander Kalinowski kept their date with Robert Greene Elliott. New York’s third ‘State Electrician,’ Elliott has been credited with perfecting the ‘Elliott Method’ still used (albeit in computer-controlled form) to this day. Appel too earned himself a footnote in criminal history. Standing before the chair he uttered the remarkable last words “Well, folks, you’re about to see a baked Appel.” In common with the gangsters of the time, he was determined to die bravely knowing that he would be remembered for not having died a coward.

The original image is dated January 13, 1953. Atom spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were condemned on March 29 for their role in passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union, a sentence still disputed today. According to the Guggenheim Museum:

“The work speaks to the constant reiteration of tragedy in the media, and becomes, perhaps, an attempt to exorcise this image of death through repetition. However, it also emphasizes the pathos of the empty chair waiting for its next victim, the jarring array of colors only accentuating the horror of the isolated, expectant seat.”

That seat certainly was expectant and with good reason. It would be occupied by murderer John Paonessa at 11pm on January 15, only two days later. In the afternoon State Electrician Joseph P Francel would arrive to test the equipment while death house guards carefully rehearsed their individual roles. They would take Paonessa from his pre-execution cell in the ‘Dance Hall,’ his home for the last twelve hours until execution or reprieve. Together with the prison chaplain they would march him around twenty feet to the chair and strap him in. With that done (preferably as quickly as possible) Warden Wilfred Denno would give the signal and Francel would earn another $150 fee.

Paonessa, only one of 614 prisoners to die in that chair, would die quickly and quietly, then disappear into obscurity. While that photograph was being taken Paonessa was sat in his cell counting the hours, hoping for a last-minute delay and probably not expecting one. He had been there since June 14, 1951, his legal options were exhausted and Governor Thomas Dewey, the former ‘racketbuster’ of the 1930’s, was in no mood to grant clemency.

This was hardly surprising. Dewey was strongly in favour of capital punishment with approximately ninety executions during his twelve years as Governor. Warden Denno, unlike several of predecessors, was also pro-death penalty. If Paonessa wanted or expected mercy he was expecting it from the wrong people.

Joseph Francel, responsible for 140 executions at Sing Sing and probably a hundred or so more in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Jersey, was an old hand. On August 8, 1942 he had even electrocuted six Naxi spies in one day at Washington’s DC Jail. At another execution, the prisoner had not died from the first jolt. Francel had stepped casually from behind the switchboard asking:

“Want me to give him another..?”

To Francel, Paonessa was just another date and another fee. Nothing special.

Paonessa himself was from Dutchess County, the last prisoner from Dutchess County to face New York State’s ultimate penalty. Convicted for abducting, beating and fatally shooting 14-year-old Robert Leonard near Poughkeepsie in upstate New York, Paonessa’s lawyer Stephen Bienieck claimed Paonessa had done it under the influence of Alfred von Wolfersdorf, Paonessa’s alleged gay lover. The motive, claimed by District Attorney W. Vincent Grady, was Leonard having seen Paonessa and von Wolfersdorf having sex which in the early 1950’s was a serious matter.

Von Wolfersdorf had cheated the chair by claiming to be legally insane. The authorities had agreed, sending him to a psychiatric institution. He would not leave until 1972. That left Paonessa, who claimed that the police had beaten his confession out of him, a confession used at his trial by prosecutor.

Faced with defending such an unpopular prisoner, Bienieck also claimed that Paonessa was mentally subnormal and had been under the control of his lover von Wolfersdorf for many years. According to Bienieck, his client was:

“Nothing but a stooge, a dupe and a puppet for von Wolfersdorf for most of his life.”

Bienieck also remarked that his client could not distinguish right from wrong, that he was:

“A mass of flesh devoid of its living instincts.”

The jury disagreed, quickly finding Paonessa guilty of first-degree murder with no recommendation for mercy. On June 14, 1951 Dutchess County Judge John Schwartz decided to deprive Paonessa of whatever living instincts he might still have possessed:

“ Jospeh Louis Paonessa, the jury having found you guilty of the crime of murder in the first degree and kidnapping, the sentence and judgment of the Court is that you suffer the punishment of death in the manner prescribed by law at Sing Sing State Prison, Ossining, Westchester County, New York on some day within the week beginning the 16th of July 1951.”

By then Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were already ensconced in Sing Sing’s ‘death house,’ having been convicted on March 29 and condemned by Federal Judge Irving Kaufman on April 5. Like Paonessa, their executions would be delayed by appeals and legal issues. They were already there when Paonessa arrived and remained until June 19, 1953 when Joseph Francel earned $200. His standard deal was $150 for a single and an extra $50 for each additional prisoner. It would also mark the beginning of the end for Francel as State Electrician.

The publicity-shy Francel had long resented the low fees and approbation for what he had done so often and so well. In the run-up to the Rosenbergs’ date with death he increasingly resented the death threats and hate mail as well. He resigned in August, 1953 after only two more executions, those of Donald Hugh Snyder on July 16 and William Draper on July 23. In the mean-time, though, his date with Paonessa was fast approaching.

All Paonessa could do was wait while more learned and intelligent people fought over whether or not he should die. January 13, 1953, the date of the photograph used by Warhol, was his penultimate full day in his death house cell before being moved to the ‘Dance Hall.’ By then Francel had accepted his latest job. Warden Denno and his men were beginning to prepare for yet another execution, a grim ritual long known as ‘Black Thursday.’

It was called that for a reason. New York death warrants specified a week, not a particular day. 11pm on a Thursday allowed the State to get a last-minute stay lifted and still have time to execute a prisoner before their warrant expired. With their last-minute delays the Rosenbergs, slated to die on Thursday June 17, would in fact die on Saturday June 19. There would be no such delay for Paonessa. The last Dutchess County prisoner to die in the chair would die as scheduled.

Paonessa, then forty-two years old, was next in line after Edward Kelly and Wallace Ford, Jr who had died on October 30, 1952. Kelly, who had been sent to the death house and released once already, hadn’t thought he would be returning, even penning a friendly farewell letter to Warden Denno. Retried and re-convicted, Kelly had been returned to the house of horrors he thought he had escaped. He would not leave alive.

Paonessa, sent to the death house in June of 1951, had already seen gangster Bernard Stein, Kelly and Ford walk past his cell never to return. Having arrived earlier, the Rosenbergs saw murderer John Saiu walk his last mile on April 12. They had missed Sing’s Sing’s latest high-profile executions by mere weeks.

Lonely Hearts Killers Raymond Fernandez and Martha Beck had died on March 8 along with murderers John King and Richard Power, convicted of murdering Detective Joseph Miccio during a bungled robbery. Paonessa’s impending death made very few headlines by comparison. The publicity from the Lonely Hearts Killers and the Rosenbergs, on the other hand, would end Joseph Francel’s career. After Paonessa the Rosenbergs would see Stephan Lewis led away on January 22, 1953, only a week later. Frank Wojcik would follow him on April 16. Then it would be their turn.

Paonessa probably had no idea that the image Warhol made famous was being taken. If his lawyer had been right then Paonessa had been unfit to stand trial in the first place. Even if he was aware of some photographer snapping away then what was about to happen probably occupied him far more. Paonessa too had a role in the preparations and not a pleasant one.

Sited away from the cells themselves, the sounds of Francel running the generator and testing the controls would not interfere with Perry Como’s hit ‘Don’t Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes’ wafting out of the death house radio, blending with the almost-perpetual cigarettes the condemned had to have guards light for them, but Paonessa must have known the situation. Even while the other hit that week, Joni James ‘Why Don’t You Believe Me,’ crooned through the cells, it was obvious that all was lost. The clock was ticking. The end was near.

Twelve hours before the appointed time he was moved from his regular cell to the dreaded ‘Dance Hall. Paonessa was made to take a bath, excess dirt would be a fire hazard when the switch was thrown. His head and right leg were carefully shaved and he was issued with Sing Sing’s custom-made ‘death suit.’ A white shirt with wooden buttons and black trousers, also with wooden buttons and the right leg slit to the knee were accompanied by a pair of shower shoes. No Sing Sing outlaw ever got to die with their boots on.

As it was, John Paonessa would die quickly and quietly without either last words or complaint. It was a textbook operation. At 11pm on January 15, 1953, barely forty-eight hours after the photograph was taken, Paonessa wlaked his last mile. Escorted by prison guards and the Chaplain he walked firmly and without delaye. He said nothing as he was seated and the straps adjusted. His last view of the world came when Francel stood before him, carefully positioning the leather helmet containing the head electrode as guards attached another electrode to Paonessa’s right leg. Warden Denno gave the signal and Francel threw the switch. John Paonessa was dead.

Leave a Reply