Executing Americans for crimes other than murder was once standard practice. Robbery, armed robbery, house-breaking, burglary and rape could all earn a death sentence in a number of States. Under Federal law, bank robbery was once a capital crime even without a shot being fired. The death penalty for rape, particularly in the South, was undoubtedly used along racial lines with far more African-Americans dying than whites. Crimes against property could be treated as severely as murder depending on where a defendant faced trial and, all too often, their ethnicity.

James Coburn, a 38-year-old farmhand and military veteran, was not executed on racial grounds. He was white and had robbed and murdered Mamie Belle Walker at Belle’s Cafe near Selma in December, 1959. His previous record included prison time for another robbery in 1949 and his claiming to be very drunk at the time won him no sympathy. Seeking the death penalty, the State of Alabama surprisingly chose not to try him for the murder. It didn’t have to. When Coburn sat in Kilby Prison’s electric chair, a notorious contraption named ‘Yellow Mama,’ it was for robbery.

Murder being the more serious crime, that seems an odd decision, but ‘Yellow Mama’ was unfussy. Regardless of colour, nationality, crime, guilt or innocence, they were all the same. Still sporting the coat of bright yellow highway paint from her installation decades earlier, all that had been available in the absence of varnish, Mama delivered equal opportunities that Alabama itself conspicuously didn’t. Since Horace DeVaughn on April 8, 1927 they had walked in, sat down and died with regularity and usually without incident. 151 convicts before Coburn, including Samuel Hall among others, had certainly kept Mama in passing trade.

Coburn, though, was a rarity. He probably wouldn’t appreciate his small place in criminal history even if he was alive to know it, but he was a rarity all the same. Nobody knew it at the time, but Yellow Mama had just claimed the last American convict to die for a crime other than murder. There were and still are death penalty laws for non-homicidal crimes, but nobody has actually died for one since Coburn. At least, not yet.

Little information exists on Coburn himself. He was born in Chilton County on January 31, 1924, died and Kilby on September 4, 1964 and was returned to Chilton for burial at the Mulberry Baptist Church Cemetery aged only forty. We do know that Coburn’s death warrant was the first to be signed by Governor George Wallace, a man revered and reviled depending on who you talk to.

Serving the first of his three terms as Governor, Wallace was one of the most openly racist politicians in American history, at least to Alabama’s voters. He certainly recanted his segregationist views later, but at the time he trumpeted racist ideas and policies as loudly and openly as possible. Second time around, his harsher stance had seen elected Governor with power of life and death over people like James Coburn.

Whether he actually held racist ideas or just used them for electoral purposes is more debatable. Wallace had lost a previous election while running on a moderate platform. In 1963 he had been elected on his infamous platform of ‘Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!’ He had attracted a lot of votes and plenty of publicity that same year, standing outside the entrance to the University of Alabama in an effort to prevent African-Americans from getting in.

His attitude to capital punishment may have been equally opportunistic. In public his attitude to the death penalty was certainly inclusive. In 1975 he remarked that:

“I hope to see some electrocutions in this State. There are a lot of bad white folks and a lot of bad black folks that ought to be electrocuted.”

His deputy, though, tells a different story and so does his signing only four warrants during his total of sixteen years as Governor. The same year he signed Coburn’s death warrant he privately told Bill Baxley, then his law clerk and later Alabama’s Attorney-General and Wallace’s Lieutenant-Governor, that he was opposed to the death penalty and thought it should be ruled unconstitutional.

By 1983 when he had to sign the warrant for John Louis Evans, Wallace was even more opposed to capital punishment. He had by then recanted his racism, become a born-again Christian and narrowly survived an attempted assassination that left him crippled for life. Unwilling at first to sign the warrant, it was Baxley who finally convinced him to do so. If he ever really held them to start with, Wallace’s racist ideas might have been and gone, or moderated, or perhaps been purely expedient, but his opportunism was as sharp as ever.

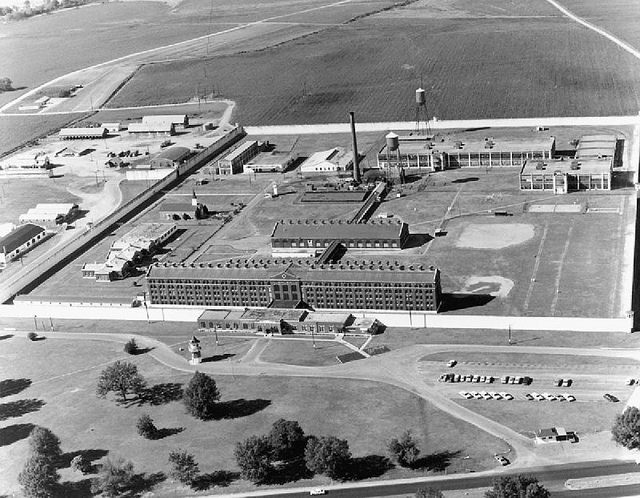

Capital punishment being popular in Alabama, Wallace needed Evans dead for political reasons. No Governor likes to seen as soft on crime and Wallace pioneered some of the harsh rhetoric, ideas and policies still in use today. Evans duly died, but in horrifically botched manner. With the old Kilby Prison closed in 1969 and Death Row moved to the new Holman Prison by the end of January, 1970, it was at Holman that Evans died. ‘Yellow Mama’ could be a cantankerous creature when she wanted to be and, like wine, had not travelled well.

Of course, none of this made any difference at all to James Coburn. Whether Walace believed Coburn deserved to die or just to appease Alabama’s voters he signed the warrant all the same. Granted, Coburn was a thief and a killer, but he was also Wallace’s first opportunity to show his ‘tough on crime’ credentials. Coburn having already received eleven stays of execution, it was time for Wallace to make an example. On September 4, 1964 he did so. The night before he was due to die, Coburn received the bad news. There would not be a twelfth stay of execution. There would be no commutation of sentence, either.

Coburn was philosophical about his impending death. He was calm when Wallace denied him clemency and had no trouble with a last meal of chicken, potatoes, bread rolls, milk, coffee and coconut cream pie. He spent his final hours quietly consulting with religious advisors. By midnight, with no appeals left to file and Wallace denying clemency and another stay of execution, it was time to go.

When Coburn entered Kilby’s death chamber he did so calmly and with a smile. He was allowed to shake hands with several of the people attending before he was strapped down a d the electrodes carefully applied. His last words made it seem almost a casual affair:

Just after the clock struck midnight Warden Clarence Burford threw the switch. At 12:14 that morning, James Coburn was dead. Before long Wallace would sign his second warrant and murderer William Bowen would die on January 12, 1965. It would be a long time before another Alabama Warden would throw the switch, John Louis Evans being Wallace’s third death warrant.

His fourth and last would be for murderer Arthur Lee Jones, electrocuted for the murders of taxi driver William Hosea Waymon and shopkeeper Vaughn Thompson. In line with his Muslim faith Jones had taken a last meal of pink salmon, coleslaw, candied yams, chilled peaches and grape drink.

Wallace denied clemency and signed the warrant despite being privately against capital punishment, at least according to Bill Baxley who had risen to Lieutenant Governor. Unlike his remarks in 1975, Wallace’s comment on Jones’s execution said nothing about his personal position on the death penalty:

“It’s a very, very difficult matter. At the same time, the law is the law.”

Wallace died in 1998. He had developed Parkinson’s Disease in his later years, although septic shock finally carried him off. His shooting by would-be assassin Arthur Bremer in 1983 had left him wheelchair-bound and with lasting pain. It was surprising, all things considered, that he survived as long as he did.

Yellow Mama long out-lived both Coburn and Wallace, claiming many more condemned convicts before its retirement. It was last used to execute Lynda Lyon Block on May 10, 2002. Block, condemned for murdering a police officer, was Alabama’s last electrocution before introducing lethal injection. Kept in reserve in case it should ever be needed, Yellow Mama resides in a storage room above Holman Prison’s death chamber gathering dust like Miss Haversham.

Yellow Mama will probably remain there, but Alabama’s recent history of botched lethal injections calls that into question. The ongoing controversy regarding the recent nitrogen gassing of Kenneth Smith, a convict Alabama previously tried and failed to kill with a botched lethal injection, still raises the question.

Will Yellow Mama make a come-back?

Leave a Reply