Before George Rutherford Harsh, Jr. became a crucial member of the Great Escape he became the ‘Milwaukee Thrill Slayer,’ at least according to the Georgia newspapers. Shot down on a bombing raid over Cologne in 1943 while serving in the Royal Canadian Air Force and a confirmed troublemaker in the eyes of his guards, Harsh found himself shipped to the legendary prison camp Stalag Luft III. It wasn’t his first taste of prison food.

As Harsh surveyed the camp he might have wondered if his fellow POW’s knew just how experienced a prisoner he was and exactly where he’d learned the tricks of the trade. They would probably have been shocked when they found out. In 1928, after seven armed robberies in Georgia, he’d been condemned to Georgia’s electric chair for murder. Decades later Harsh admitted it was his second murder and he had committed three in total.

Having been spared electrocution, he served 12 years at the notoriously-tough Georgia State Prison before being paroled and pardoned. After his release Harsh headed for Canada, joining the RCAF to redeem himself. It proved a tough, dangerous route to redemption in a society that had rejected him and almost killed him.

He was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1909, the son of a wealthy businessman whose success meant ‘Junie’ as he was known, wanted for nothing. Well, nothing except the excitement denied him by simply clicking his fingers and getting whatever he wanted, whenever he wanted it. His attitude to life and the world, not that warm to begin with, had worsened after father died during surgery in 1921.

Affluence and easy living had bored him to the point where pretty much anything might seem more interesting. He entered Oglethorpe University in Georgia, quickly making friends with fellow wealthy layabout and ne’er do well Richard ‘Dapper Dan’ Gallogly. With a couple of other young swells who have long disappeared into obscurity, Harsh and Gallogly began a spree of armed robberies in Georgia until falling from grace with a terrible thud.

Harsh drank heavily and was considered a nasty drunk by those who’d seen him intoxicated). Easily bored, he and Gallogly cruised round in an expensive car shooting out streetlights with a .45 automatic. That gun took the lives of two innocent shop clerks and very nearly Harsh and Gallogly’s as well. The deal was simple. Gallogly was the wheelman and look-out while Harsh did the actual robbing.

Harsh later admitted murdering E.H. Meeks during the second of their seven robberies although he was never charged. He certainly was charged with murdering Willard Smith. Smith had often boasted he would never allow anybody to rob the store and, while his aim was good enough to seriously wound Harsh, Harsh’s trusty .45 served him better. Or so he thought.

He didn’t think so after being shot in the hip while murdering Smith and bleeding profusely all over his trousers. A maid had unwittingly sent those same trousers to be dry-cleaned and police quickly traced the laundry marks to Harsh and Harsh to Gallogly. Harsh then informed on Gallogly while confessing to murder and armed robbery, perhaps thinking a quick confession might spare him the full rigors of Georgia justice. It didn’t.

Then as now Georgia took a hard line on murderers including Yankee ones who brought violence and trouble from up North. Being white was no guarantee of avoiding the death penalty. Georgia now had two chances to end Harsh’s criminal career permanently. If he was acquitted of murdering Smith they could still try him for murdering Meeks. Georgia made no bones about its death penalty. Suddenly a short walk to a not-so-comfortable chair loomed large in his future.

Harsh and Gallogly went on trial for murder in January, 1929. Their wealthy families couldn’t get Clarence Darrow, but at considerable expense they did hire a former member of Georgia’s House of Representatives, William Schley Howard. Given that Harsh had already confessed, Howard felt his best strategy was to try convincing the jury that Harsh was legally insane and so not criminally responsible.

With that in mind he assembled a battery of psychiatrists and a witness from Milwaukee who testified to seeing Harsh suffer a head injury during a childhood accident. Howard spoke eloquently, as did his witness and battery of experts. Unfortunately, the prosecution’s experts proved more persuasive. So did chief prosecutor John Boykin asking them to send Harsh to the electric chair. After a four-day trial in January, 1929 the jury deliberated only 15 minutes, finding him guilty as charged without recommending mercy.

With a guilty verdict, no recommendation for mercy and a prosecutor stridently demanding the death penalty the case seemed to be over. Harsh was transferred to Death Row where on March 15, 1929, according to Judge E.H. Thomas, he would die “By electrocution in private, witnessed only by the executing officers, his relatives, counsel, and such clergymen and friends as he may desire.” Quickly transferred from Fulton County Jail to Georgia State Prison, Harsh had reached the end of the line. His last stop would be a large, white-painted chair Georgians already called Old Sparky.

The outlook was grim indeed. Georgia executed over fifty convicts between 1925 and 1930, mostly African-Americans, and Southern justice was seldom anything but (no pun intended) harsh. At least it might have been but for the interventions of co-defendant Richard Gallogly (despite Harsh’s betrayal) and their rich, well-connected families. With connections and money to burn, Harsh’s allies had no intention of letting Georgia do the same to him.

Gallogly fought his case through three separate trials. The first two ended in hung juries. The third resulted in a life sentence, Gallogly pleading guilty in 1930 in return for the commutation of Harsh’s death sentence. With that in mind and under informal pressure from the families, Harsh’s sentence to commuted to life. Harsh had escaped Death Row, but only into Georgia State Prison’s general population. Once there he languished on one of Georgia’s infamous chain gangs for the next several years.

While Harsh seemingly embraced Georgia’s dog-eat-dog penal system, Gallogly didn’t. He hated prison life, especially being picked on for being rich, white and privileged. In 1932 he attempted suicide. In October, 1939 he suffered a mental breakdown and was transferred to hospital. While returning to prison he hijacked the car with a fake gun (a car belonging to Georgia Prisons Inspector Royal Mann, no less) and reached Texas where he surrendered. Despite turning himself in he fought extradition to Georgia and failed, returning under armed guard in March, 1940.

By then Harsh was a hard-timer well-used to the hardships of convict life. Both his and Gallogly’s families were still working hard to persuade Georgia’s Governor to grant pardons. Harsh helped considerably when, after years as a convict nurse at Bellwood Prison Camp, he helped perform an emergency appendectomy on a fellow-inmate. Foul weather had made it impossible for the prison doctor to arrive in time to save the patient’s life but Harsh, once a killer facing electrocution, had saved a life and was duly rewarded.

Harsh found himself released on November 23, 1940 on the recommendation of the Georgia Prison and Parole Commission. Still better was to follow. Mindful (and perhaps tired) of the endless lobbying, Governor E.D. Rivers pardoned both men on January 13, 1940. George Harsh, rich layabout, young thug, armed robber and former condemned murderer, was once more Mr. George Harsh.

At first his return to normal society went poorly. Harsh needed money and work at a time when the country was still trying to shake off the Depression. Unfortunately, there were few Georgia employers, even those with jobs to offer, prepared to risk hiring former Death Row inmates. In fact, the best offer he did get came from an Atlanta crime syndicate needing another enforcer.

With his prior record Harsh knew any additional jail sentence would probably mean life and for another murder he wouldn’t walk out of Death Row twice. Dispirited, he moved up north to Toronto and drink heavily while brooding over his problems and hoping, rather than expecting, to find a solution. The solution came faster than he’d dared hope, though at considerable risk.

America hadn’t yet joined the Second World War, that didn’t happen until Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. But some young Americans were already making their own way over to England and enlisting in such units as the Royal Air Force’s ‘Eagle Squadrons’ or the Royal Canadian Air Force. Harsh, being a skilled marksman and having decided to try redeeming himself, joined the RCAF.

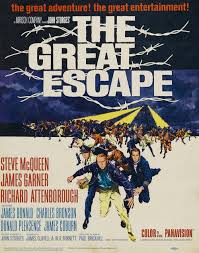

He graduated top of his class as a tail gunner, the most dangerous assignment on bombers, and went to a bomber squadron where he was shot down over Cologne in 1943. After numerous disputes with his captors Harsh found himself at the supposedly escape-proof Stalag Luft III where he took his vital role in keeping the very existence of the ‘Great Escape’ a secret from the guards.

He took no part in the escape itself, having been transferred to another compound shortly before the tunnel (codenamed ‘Harry’) was completed. That disappointment might have saved his life. Of the seventy-six POW’s who escaped on March 24, 1944 only three made it back to England. Of the seventy-three recaptured, fifty were murdered by the Gestapo. Harsh wasn’t one of them. He was liberated and repatriated at the war’s end and never again had trouble with the law. The former armed robber, killer and dead man walking had finally become a law-abiding citizen.

After the war he worked as a book salesman and tried his hand at running a tree nursery. He also published his memoir ‘Lonesome Road’ and spoke out against the death penalty in his final years. He also finally admitted a third murder, having knifed another convict in a dispute over a cake of soap. Had he done so decades earlier, far from being pardoned and paroled, he could have escaped the chair once only to face it again.

In the early 1970’s he returned to Canada, living in Toronto with old friend, fellow-escaper and Stalag Luft III ‘Tunnel King’ Wally Floody. Living out his twilight years as an honest citizen, Harsh finally died of a heart attack on January 25, 1980 while running for a bus.

Leave a Reply