The 1890’s spawned both the electric chair and a rash of murder by morphine. Unlike today morphine was far more easily obtained and, with forensic science still evolving, far harder to detect. Carlyle Harris and Robert Buchanan, a medical student and doctor respectively, are prime examples. They are forever linked by morphine, murder, the electric chair and their unwilling contributions to forensic science and toxicology. Neither would have appreciated their dubious distinction.

It’s often said that a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing and that pride comes before a fall. Harris and Buchanan amply prove both theories. Both thought themselves too clever to be caught. Both used their medical knowledge in ways utterly at odds with the Hippocratic Oath. Having both committed the ultimate crime, both paid the ultimate penalty.

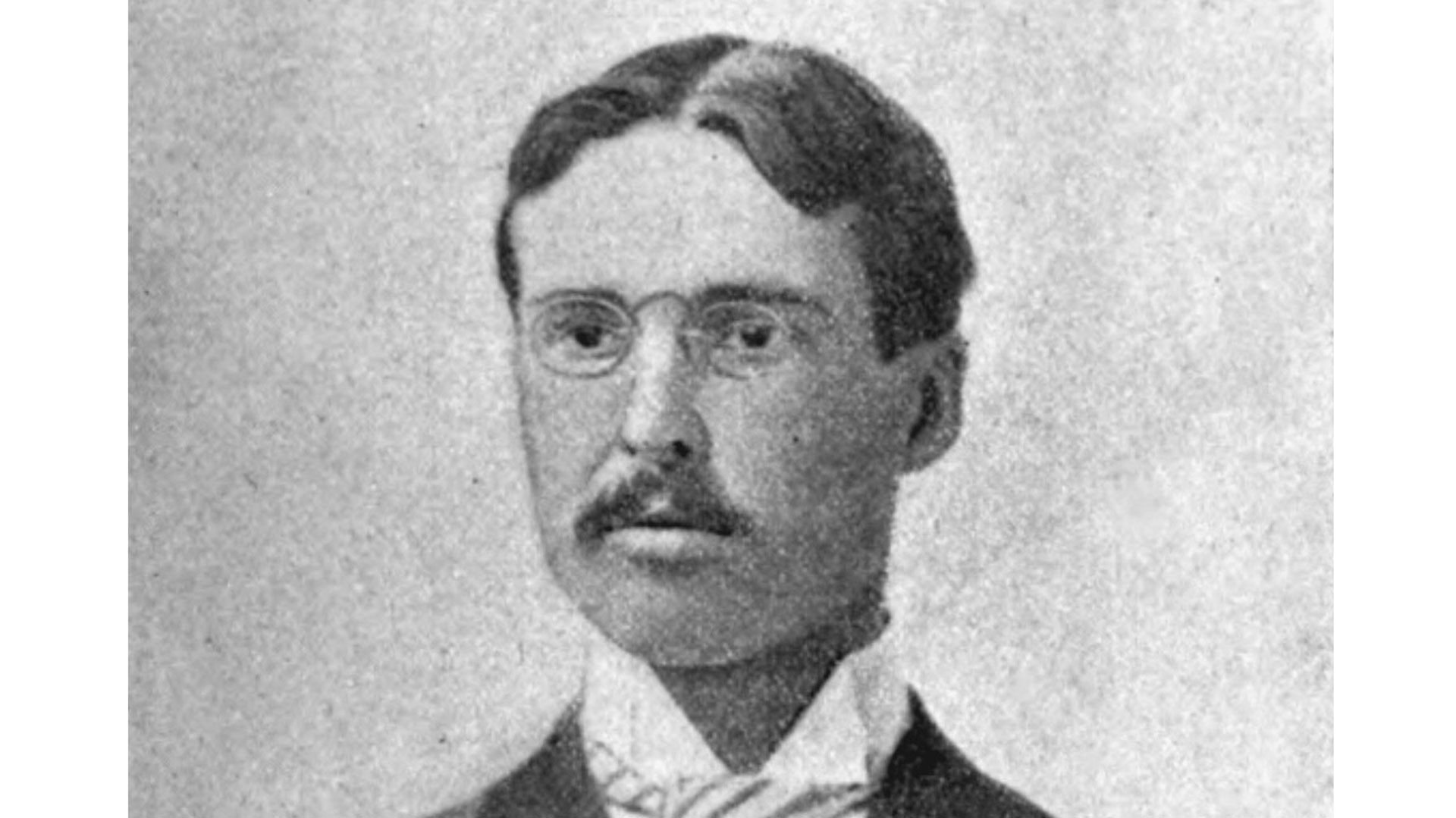

Born to respectable upper-class parents in Glens Falls, New York in September, 1868, Harris was a medical student by training and libertine by inclination. In fact he’d probably be considered a sexual predator today. One of his friends later described Harris’s treatment of women, saying Harris once told him he:

“Could overcome any woman’s scruples… One method was to take a bottle of ginger ale and put in it a very large portion of whiskey, the other was to marry her, but under an assumed name.”

Studying at New York’s prestigious College of Physicians and Surgeons did nothing to curb Harris’s libido or improve his treatment of women. It did give him access to women and morphine, both of which he used entirely unscrupulously. Marriage hadn’t improved his attitude either.

His young wife Helen thought the world of him, probably because she never really knew the man she’d married. Her family had begged to differ. They’d thought him a poor match from the beginning but, love being what it is, Helen ignored their concerns and married him anyway. The more her family disapproved the more she liked him. It was to prove a fatal mistake for both of them.

Harris enjoyed appearing to be a young, educated, respectable young man-about-town albeit something of a lady-killer. In reality a lady-killer was exactly what he was. Behind the respectable façade lurked a dark, cynical, ruthless exploiter of other people, especially women. Infidelity, carousing and money interested him far more than his studies. Harris also had expensive tastes for a student and was keen to reserve his respectability, sham though it was. He was so keen he was prepared to kill for it. In 1891, he did exactly that.

On February 1 of that year wife Helen was found desperately ill in her room at Comstock Finishing School. A nice, decent young lady, she was exactly the sort of young woman who passed through Comstock’s doors every year before debuting on the New York society circuit. Doctors were immediately summoned but Helen, seemingly having suffered some kind of stroke, was incoherent and rambling. She was also dead within a matter of hours.

A sudden stroke or aneurysm was tragic in a woman not yet past her 19th birthday, but not so unusual that it wasn’t the doctors’ initial diagnosis. It was an entirely legitimate, unsuspicious way to die. Neither the diagnosis nor its legitimacy stood much scrutiny. It wasn’t long before it was discarded. On examining her more closely doctors noticed something untypical for a stroke victim. When they looked into her eyes the answer literally stared them in the face. Pinpoint pupils might not be typical for a stroke but they are typical of something much less natural and far more sinister; Morphine poisoning.

The first item on their agenda was to confirm that Helen actually had died of a morphine overdose. Today’s toxicologists could order a battery of tests, obtaining a reliable result in days or even hours if a case was urgent enough. Modern tests could not only confirm its presence and estimate how much was administered from the residue left behind. In 1891 toxicology was far less advanced. Even proving the presence of morphine in a potential murder victim was difficult and Carlyle Harris knew it.

Harris, a medical student, probably chose morphine for precisely that reason. He’d grasped the theory of the perfect murder, or so he thought. The perfect murder goes unseen, not unsolved. If passed off as accident, suicide or illness it goes uninvestigated. To preserve his outwardly-respectable image and protect his reputation Harris was prepared to murder the person who trusted him most, but why?

Harris had met 18-year-old Helen Potts at Ocean Grove in 1889. Their attraction was both instant and mutual. Harris enjoyed the company of a respectable, well-mannered young lady. She in turn was equally smitten with who she believed was a decent, respectable young gentleman. Harris was anything but decent and respectable. Despite being only twenty and not yet a qualified doctor, he still proposed marriage.

Helen was overjoyed but her parents, skeptical about how a young student would support their daughter, vetoed the wedding. The young lovers were bitterly disappointed. Permission had been denied and while it wasn’t legally required it certainly posed a serious problem. Eloping was something they considered but would cause great embarrassment in higher social circles. So, without changing the minds of her parents, a secret wedding was the only option.

Had they eloped things might have turned out very differently. Helen Potts might not have been murdered and Carlyle Harris might not have gone to the electric chair. As it was the couple had to enjoy both their marriage and conjugal rights in secret. In time that secrecy sealed both their fates. The ceremony, a fraudulent one, was held secretly on February 8, 1890. Helen used a false name, becoming Helen Nielson while Carlyle Harris became Charles Harris for the occasion. Helen Nielson and Charles Harris (according to their marriage certificate) had practiced a crude deception. It was still successful, at least for a while.

In August, 1890, around the time William Kemmler debuted Auburn Prison’s electric chair, Helen’s mother found out. Helen had become dangerously ill with a post-operative infection, what was then called ‘septic poisoning.’ It transpired that she’d endured a series of secret operations (possibly illegal abortions) performed by none other than Carlyle Harris.

Harris, not even a qualified physician, still thought himself a competent surgeon. When her chronic pain and misery became too much for her Helen had confided in her uncle. He in turn informed her mother. The secret had gone as far as the Potts and Harris families and soon it would be common knowledge across the entire country.

Despite (or perhaps because of) their marriage the couple still weren’t actually living together. Harris had a home of his own but he somehow induced Helen’s mother to send her to Comstock. To keep things within the families the couple would have to be properly introduced to New York’s society circuit and their irregular marital status somehow glossed over. That plan died with Helen on February 1, 1891. Less than a year after their sham wedding the bride was dead. Her husband was about to be indicted for murder.

Harris had been clever, but not clever enough. Suffering from insomnia and pain from her husband’s attempts at surgery, Helen had asked to get her something, anything, to help her sleep. Harris had provided capsules (then quite a new invention) from the teaching hospital’s own pharmacy. She was to take one every day with a drink of water.

His trap now set, all that remained was for Helen to spring it. If she died his secret would be kept, his respectability preserved and he could go back to his life of carousing and sleeping around. If women were sympathetic to a young widower then so much the better. He’d find it even easier to exploit them than he had before.

If she lived she was both a burden and might one day expose him accidentally or otherwise. In the process his reputation would be destroyed. In an age where a gentleman’s reputation was his ticket to wealth and success, Harris would be personally and professionally ruined regardless of whether he graduated from medical school.

Harris knew where Helen kept the capsules. He knew where to obtain morphine and how difficult it was to detect. He also knew he needed to look appropriately shocked and surprised when his wife ‘accidentally’ died. With that in mind doctored one of the capsules at random, slipping in a lethal dose of morphine. He didn’t know when she’d take it. Once she had he’d simply accuse the hospital pharmacist of bungling the prescription with lethal effect just as any distressed, grief-stricken husband might do. In effect Harris was playing a different form of Russian Roulette. So was Helen, only she didn’t know until after she took Harris’s poison pill.

Unsurprisingly her mother was immediately suspicious and demanded a full investigation. Once morphine became the likely cause of her daughter’s death Doctor Allan Hamilton and Professor Rudolf Witthaus proved it scientifically using the Pellagri test. On March 23, 1891 Harris was arrested after a Grand Jury indicted him for first-degree murder.

His trial opened on January 19, 1892 with Recorder Smyth presiding. His parents had retained eminent lawyer William Howe (unsuccessful defender of Harry Carleton). Assistant District Attorney Charles Simms, Jr led the prosecution. Society reporters and gossip columnists had a field day. Lurid tales of Harris’s womanizing and carousing, his double life, the secret (and fraudulent) wedding, morphine and murder lit up front pages across the country.

To add more spice to the dish it was a capital case. Would Harris walk free, acquitted without a stain on his character? Or would he walk instead from a cold, damp, gloomy cell to the electric chair? As the jury deliberated reporters, columnists, society mavens and ordinary New Yorkers excitedly awaited their verdict. On February 2, 1892 they got it. After deliberating for only eighty minutes the jury returned their verdict; Guilty as charged with no recommendation for mercy.

The prosecution’s case, especially the forensic evidence of Doctor Hamilton and Professor Witthaus, had been overwhelming. With no recommendation for mercy Recorder Smyth could pass only one sentence; death. Harris was immediately escorted to Sing Sing to await execution. In January, 1893 Harris’s appeal was heard, considered and rejected. His lawyers went before Smyth arguing for a new trial. They had, they said, new evidence that hadn’t been presented at Harris’s original trial. Smyth denied a new trial on March 16. On March 20 Smyth set a new date. Carlyle Harris would die on May 8, 1893.

Governor Roswell Flower was Harris last hope. His lawyers bombarded Flower with requests for clemency, as did many letters sent from all over the nation. The pressure did force Flower into ordering a special commission to review Harris’s case but they refused to recommend mercy. Without the commission’s recommendation Flowers followed suit.

At dawn Harris walked into Sing Sing’s death chamber before an audience of reporters and prison officials. He pled his innocence one last time. State Electrician Edwin Davis waited for the signal. Warden Charles Durston (who supervised William Kemmler’s execution) had taken over at Sing Sing only a few days earlier. Durston, lacking any relish whatsoever for executions, reluctantly signaled Davis. The switch was thrown, the dynamo hummed and Carlyle Harris was dead.

Doctor Robert Buchanan wasn’t, at least not yet. Another outwardly-respectable gentleman with an inward love of drink and debauchery, Buchanan had actually finished his medical training. When Harris went on trial for his life Buchanan, a Canadian from Nova Scotia, was running a successful New York City medical practice.

Unlike Harris, Buchanan actually was a qualified doctor. Like Harris he had expensive tastes and was a rampant womanizer, although preferring brothels and bordellos to impressionable young debutantes. That he too was married also did nothing to curb his appetites for wine, women and song. His desire for money led him to murder. His fondness for drink and bar-room boasting opened the death house door.

Buchanan was fond of nightlife, drinking and was a bar-room blowhard. He loved looking down his nose at anyone he thought his inferior (which was most people). During the trial Carlyle Harris was his pet subject of sneers and general derision. Harris was both a “Stupid amateur” and “Bungling fool” according to Buchanan. In his opinion any half-competent killer, especially one with medical training, would have known pinpoint pupils were a cardinal sign of morphine poisoning

With that obvious warning staring them in the face, Buchanan declared any real doctor would immediately make the right diagnosis. Any real murderer, Buchanan sneeringly stated, would have known how to hide something so obvious. Had Harris possessed Buchanan’s knowledge and intellect he would have dripped atropine into Helen Potts’s eyes. Then he might have got away with it. To Buchanan Carlyle Harris had died for being an incompetent fool, not for being a cold-blooded murderer.

Buchanan’s speechifying might have entertained his audience and gratified his ego, but it would come back to haunt him. So too would the ghost of his second wife Anna. Born Anna Sutherland, she’d been a brothel madam with a foul mouth and a penchant for hard liquor. Buchanan had met her during his nightly rounds of New York’s many brothels and bordellos. Having grown tired of Annie, his respectable first wife who inexplicably remained loyal to him regardless, Buchanan made one of the worst decisions of his life. In 1891 he divorced her and Anna Sutherland became Anna Buchanan. He also installed her as receptionist at his medical practice.

For a man of expensive tastes and licentious lifestyle he’d just made an extraordinarily bad business decision. Previously seen as a respectable gentleman, his patients didn’t take well to his leaving his respectable wife for a tipsy, profane brothel-keeper. They took even worse to having be seen speaking to her when they visited his surgery. Before long increasingly fewer patients were attending appointments and Buchanan’s business began to suffer. His high living and debauchery had started to catch up with him.

Social standards at the time dictated that debauchery be discreet and kept a strictly private affair. Men (but never women) could indulge all manner of vices provided they were conducted quietly and behind closed doors. Buchanan’s mistake was being as defiant in public as he’d been debauched in private. His licentious life was crippling his finances and without money he couldn’t indulge himself as he so loved to.

With his own resources rapidly dwindling Buchanan now looked to those of his now-inconvenient second spouse. Anna’s death would rid him of the perpetual embarrassment she’d become. She was also worth around $50,000. It didn’t take long for Buchanan to see an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone and his wife with a morphine overdose.

On April 26, 1892 Anna Buchanan (nee Sutherland) suddenly died. Like Helen Potts doctors initially believed she’d suffered a stroke. Anna Buchanan didn’t provide the pinpoint pupils that, with Harris’s case still recent, would have caused immediate suspicion and probably investigation. Without the eyes to see anything unusual and with Buchanan a fellow physician, her doctors declared nothing was wrong.

Anna Sutherland’s friends weren’t fooled anywhere near as easily. They were suspicious from the start, suspicions that only grew when Buchanan pocketed her estate and made another dreadful decision. Three weeks after the death of his second wife Robert Buchanan remarried Annie Patterson. The former Mrs. Buchanan was now the current Mrs. Buchanan, again.

The remarriage caught the attention of Sutherland’s friends which was unsettling enough for the deadly doctor. Worse was to come when bar-room chatter, one of Buchanan’s favorite pastimes, caught the ear of New York World reporter Ike White. Like all good reporters White sensed a story or at least the chance of one. He began taking a closer look at Doctor Buchanan.

White quickly confirmed Sutherland’s shady relationship with Buchanan. Digging deeper he uncovered Buchanan’s inheritance when Anna died and his speedy remarriage to first wife Helen. It wasn’t long before the reporter’s nose sniffed out some far more salacious information, specifically Buchanan’s nightly debauchery and trawling of New York’s sex trade. Perhaps most suspicious of all, Buchanan had been holding court in a crowded bar during the Harris trial.

White pursued the story relentlessly, demanding Anna’s body be exhumed for an autopsy. Buchanan had good cause to be worried. When she died he could have cremated her, thus hiding any usable evidence of morphine poisoning. It being cheaper he’d buried her instead. Another bad decision was about to come back to bite him. So too was his recently-deceased second wife.

Professor Witthaus now entered the fray. Like Harris, Buchanan hadn’t been quite as clever as he’d thought. Again using the Pellagri test Witthaus discovered one-tenth-of-a-grain of morphine, estimating it to be the residue of five or six grains. Five or six grains was almost certainly a lethal dose for anyone without any tolerance for opiates. He also tested Anna’s eyes for atropine and quickly found it. Doctor Robert Buchanan was immediately arrested and charged with first-degree murder.

His trial opened on March 20, 1893. Earlier that day Recorder Smyth had resentenced Carlyle Harris to death after an unsuccessful appeal. Now, having presided at Harris’s trial and resentencing he sat in judgment on Robert Buchanan. It was another feast for newspapers and their readers. Another round of public morality versus private debauchery was eagerly lapped up by New York’s press and public.

Harris’s trial had been noted for the victim’s pinpoint pupils. Buchanan’s entered forensic and criminal history not for the victim’s eyes, but for Witthaus proving Buchanan’s theory about hiding them with atropine. For a man so fond of being right Buchanan must have wished devoutly that for once he’d been wrong. Once entered into evidence beside witnesses accounts of his bar-room boasting his clever idea and loud mouth weighed heavily against him.

His lawyers protested bitterly at how Witthaus proved their client right. First Witthaus killed a stray cat with a morphine overdose. Having done so he invited the court to watch as he dripped atropine into the unfortunate animal’s eyes. Its eyes, contracted to morphine’s trademark pinpoints, suddenly dilated to near-normal. Witthaus had noted in his original report that: “Treatment of the eyes with atropine might well eliminate the narrowing of the pupils which otherwise follows morphine poisoning.”

While answering questions from lead prosecutor Francis Wellman, Witthaus had made forensic and legal history. It was doubtless no satisfaction to Buchanan that so distinguished a scientist had proved him absolutely right. Morphine might have temporarily eased his financial difficulties, but New York’s cure for murder was far less gentle.

As much as anything else Witthaus’s tests and Buchanan’s own mouth convicted him. On April 26 the jury announced he was guilty of first-degree murder with no recommendation for mercy. State Electrician Edwin Davis now had another date in his increasingly crowded diary. So did the disgraced Doctor Buchanan. The date of his conviction was also a bad omen, exactly one year to the day after he poisoned Anna Sutherland.

The usual appeals were quickly filed and were just as quickly denied. At Sing Sing all Buchanan could do was wait, hope and possibly pray. Perhaps he also rued the day his bright idea and big mouth had set him on the road to the death house. With every failed appeal he took another step along the same road as the man he’d so publicly lampooned, Carlyle Harris. When Buchanan entered the condemned cells at Sing Sing he was probably a little embarrassed to finally meet the ‘stupid amateur’ and ‘bungling fool’ he’d so disastrously mocked. Buchanan had had the first laugh. Harris laughed last and longest, but had little time left to do it.

Harris, sat only a cell or two away from Buchanan, only had to endure Buchanan’s company briefly. He paid for murdering Helen Potts on May 8 shortly after Buchanan’s arrival. Whether Harris, by then devoid of all hope, particularly minded getting away from Buchanan isn’t known. Perhaps having recalled Buchanan’s public remarks, it might have given Harris some small satisfaction to see Buchanan also on death row.

Either way Carlyle Harris was gone. Whether Buchanan faced the same fate was out of the disgraced doctor’s hands. Either the courts would find reason to set him free or the Governor would offer clemency. Buchanan firmly believed that one or the other would save him. He was wrong. It was unlikely that the courts or Governor would intervene. The trial had been fairly conducted. The evidence, especially the findings of Professor Witthaus, had been more than adequate. Buchanan’s licentious lifestyle and arrogant, sneering demeanor during his trial hadn’t won him any friends either.

Between Harris on May 8, 1893 and Buchanan on July 1, 1895 New York State electrocuted eleven prisoners at three different prisons. Anticipating far more executions than there actually were, the state had built chairs at Sing Sing, Auburn and Dannemora. By 1915 it was obvious that only one chair was needed and only Sing Sing’s was retained, now housed in the first death house kept solely for condemned inmates. New York’s penal system had something new and intended justifying its controversial existence by using it as regularly as possible. With all that in mind Buchanan and Harris had arrived on death row at a particularly bad time for any condemned prisoner still hoping for mercy. Neither of them got any.

Just as the courts and Governor hadn’t saved Harris, they didn’t save Buchanan. Governor Flowers had been replaced by Levi Morton and Morton was in no mood for mercy. Buchanan’s would be the third of ten men to die during Morton’s two-year term in office. The last on April 14, 1896 would be German merchant seaman Carl Feigenbaum, still listed today as one of the suspects who might have been Jack the Ripper.

When his time came Buchanan died calmly without any mechanical mishaps or melodrama. On July 1, 1895 his time finally ran out. Convinced to the end that Governor Morton would grant clemency Buchanan was stoic when Warden Omar Sage arrived just before the appointed time. There was no more time, Sage told him. The Governor wasn’t going to intervene.

At 11:20am he walked the few steps from his cell, sat down and silently closed his eyes. He said nothing as the straps and electrodes were applied. At 11:21am Edwin Davis threw the switch. Buchanan, barely alive after the first jolt, didn’t survive the second. After his autopsy Mrs Buchanan arrived to claim his body, but lacked the money to make the arrangements.

Something had to be done for the grief-stricken Annie Buchanan. A sympathetic Warden Sage started a subscription drawing contributions from most of the officials and witnesses to Buchanan’s execution. They had little sympathy for her husband, but plenty for his sobbing widow. Morbid sightseers unfortunately did not. With the money provided by Warden Sage and the other donors Helen Buchanan had her husband’s body taken by train to New York City.

At the undertaker’s she viewed him for the last time while a large crowd gathered outside. Embracing him she kissed him and sobbed: “Oh Robert, Robert. You are gone from me and how I loved you!” Lawyer George Gibbons and the undertaker tried to lead her away. She refused to be separated from her husband’s bod. Again she broke down and sobbed:

“No, no. They shall not take you from me! Oh, my Robert!”

It was a thoroughly distressing scene for all involved. Just as Robert Buchanan had been carried from Sing Sing’s death chamber his widow was virtually carried away from her executed husband. He was laid to rest mere days later, this time without the unnecessary public attention.

Harris and fifteen other historic New York cases can be found in my book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York,’ published by Fonthill Media and America Through Time.

Leave a Reply