A free chapter from my book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York,’ available now.

Like it or not, some murders become an entity bigger and more lasting than themselves. Murderers have been seeking to rid themselves of inconvenient spouses, partners or ex-partners since murder existed, there’s nothing unusual about it. Seldom though does the murder of an inconvenient partner have so lasting a legacy as that committed by Chester Gillette at upstate New York’s Big Moose Lake on 11 July 1906.

When he murdered pregnant girlfriend Grace Brown, beating her unconscious with a tennis racket before tipping her into the lake to drown, he had no idea that his cultural legacy would long outlive both him and his innocent victim.

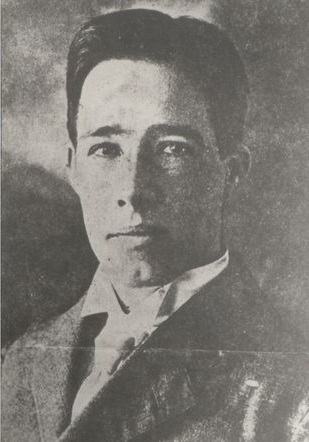

A foolish and immature young man, Gillette wouldn’t live to be an old one. Dying in Auburn Prison’s electric chair on 30 March 1908, Gillette would never read Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy. He would never see 1951 movie A Place In the Sun starring Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor or hear 1926 folk song The Ballad of Big Moose Lake either.

That said, neither would poor Grace Brown. She deserves infinitely more sympathy than her murderer.

Herkimer County’s last well-known murder case was that of Roxalana Druse. From 21 September 1885 to October 6 her story made news all over the state. She was also the last woman hanged in New York State and her suffering prompted New York’s legislators to replace its gallows with the electric chair. Gillette would sit in the same jail and be tried in the same courthouse. He would die in the contraption Druse’s suffering helped bring into being.

Chester Gillette was born into a comfortably wealthy family in Montana on 9 August 1883. His upbringing might have continued being comfortable if his highly-religious parents hadn’t joined the Salvation Army. Spurning material wealth they travelled from posting to posting spreading the word. Chester didn’t especially take to religion until it was far too late. He didn’t take well to a life of constant changes and virtuous poverty either. Montana, Wyoming, Washington State, Oregon, Hawaii and California all played host to the Gillette family at different times.

That hadn’t made for a particularly settled and stable upbringing. It might account for Chester becoming a shiftless young man seemingly unable to settle down anywhere for long. Nor, his parents noted, had their son had a particularly settled, stable education. He was bright but not especially committed to anything, a dilettante.

It was probably the money or connections of his wealthy uncle Noah (possibly both) that saw him sent to the private, prestigious and very expensive Oberlin College in Ohio. Still as revered today as it ever was, the chance to study at Oberlin was something more assiduous but poorer students would have jumped at had it been offered. It didn’t turn out as his parents and uncle had hoped.

Oberlin remains a revered institution, not one to put a notorious murderer on their long list of notable alumni. Fortunately for Oberlin they don’t have to. Perhaps the constant changes of place and school left him reluctant or unable to settle at Oberlin or perhaps he just didn’t want to. While his grades were perfectly sound his attitude wasn’t and he dropped out after only two years. Academia’s daily grind simply wasn’t for him.

A succession of odd jobs followed in a variety of different places. By 1905 Gillette was working in Chicago as a railway brakeman when Uncle Noah came calling. It was time for the lost sheep to return to the flock and take a respectable job at his uncle’s prosperous business in Cortland, New York. Following his uncle to Cortland, Chester started at the Gillette Skirt Factory. Unfortunately for all concerned that was also where he met young Grace Brown. The first act in this American tragedy was about to begin.

Being young, charming, handsome and the boss’s nephew would certainly have attracted the attention of female factory workers at all levels. From the outside Gillette was a potential catch and had the ear of their employer. On the other hand he was also in a higher social bracket than most of them. Many wouldn’t have risked their jobs or a scandal by setting their cap at the boss’s nephew. Grace Brown was different. She saw something in him that she genuinely liked and that was her downfall.

Exactly how they met isn’t clear. They worked in different parts of the factory and would seldom have come into contact. Moving in entirely different social circles would have widened the gap still further. Grace was only one of many female workers at the factory and Gillette was on a higher professional and social level. That didn’t keep them apart and it was likely Gillette who made the first move.

Grace was a farmer’s daughter for South Otselic. Born in 1886 she’d moved in with sister Ada in Cortland, trading an idyllic if stifling rural life for the bright lights and big city. Wanting to keep busy and contribute to the household Grace had sought work and Gillette’s employed her in quality control, checking products before they left the factory.

She was pleasant if perhaps naïve in the ways of the opposite sex, particularly young, charming and handsome ones like Chester Gillette. Gillette was a little less innocent having been immersed in the ways of tough towns like Chicago while on his travels. Grace might have been his main girlfriend but far from the only one. In those rather more strait-laced times she wasn’t very happy about his playing the field. His family weren’t entirely approving either, considering their difference in background.

While Gillette was content to play the field, apparently being seen with a number of other women, Grace was invariably upset by regular rumours about his conduct. In the spring of 1906 the situation came to a head when a distressed Grace dropped a bombshell on her wayward beau; She was pregnant. She wanted him to marry her.

To Gillette this was a disaster. He’d been content to arrive for work in the mornings and play the field in the evenings. The morals of the time being what they were, he’d have to give up his carefree existence and knuckle down to being a husband and father. Worse still he’d have to marry someone far lower in the social pecking order. For a man wanting to move up life’s ladder marriage and the embarrassing reason therefore would ruin him. If she were to take her own life Gillette’s behaviour would be every bit as exposed. In her letters she’d implied as much:

“Chester, if I could only die. I know how you feel about this affair, and I wish for your sake you need not be troubled. If I die I hope you can then be happy… My life is ruined and, in a measure, yours is to. The world and you, too, may think I am the one to blame, but somehow I can’t. Just simply can’t think that I am. I said no so many times.”

Not being the most mature, wisest or honourable of men, Gillette decided to ignore the problem and hope it would go away. Of course, it didn’t go away although Grace returned home to her parents which might have convinced him it had. Further rumours about his womanising saw her come back and Gillette was trapped. Facing a life of respectable responsibility his thoughts turned to making his problem disappear again, this time permanently.

The golden summer of 1905 when he and Grace represented love’s young dream was now a distant memory. For Gillette it must have seemed to be all downhill from there. His girlfriend was pregnant, unmarried and pressuring him to protect both their reputations. Rumours were floating around like storm clouds and relations with Grace were steadily worsening. She kept pressing for commitment and marriage, neither of which he was ready, willing or perhaps able to give. Facing this intolerable situation Chester Gillette hatched a plan that would be fatal to both of them.

Gillette’s plan started with luring Grace to Big Moose Lake in the Adirondacks. He didn’t pack much, taking only his monogrammed suitcase, camera, tripod and tennis racket. Grace, on the other hand, brought her entire wardrobe probably thinking marriage (or at least elopement) were on the cards. She’d written to him a number of times applying further pressure and expecting yet more excuses.

She’d also issued an ultimatum: “I expect any time to hear you can’t come for a week or two – yet I am awfully sorry, but I have planned on Saturday and I shall be in Cortland that night.” In other words she was planning to come to him unless he came to her, possibly to expose him for what he was. Gillette, meanwhile, was preparing to do whatever it took to silence her.

The couple met aboard a train at DeRuyter as agreed, but with one small deviation. Gillette’s hotel reservation had been in the name of Charles George, an alias matching the initials on his monogrammed luggage. Continuing to Utica they registered as Charles Gordon and Wife. Grace was aware of the false names. She didn’t know they’d left Utica without paying their hotel bill. ‘Charles George and Wife’ then stopped again, this time at Tupper Lake Village.

By July 11 what Grace thought might have been a joyous elopement had turned entirely sour. At one point a hotel employee had to escort her out of the dining room in tears. It was obvious that whatever she’d expected to happen wasn’t going to. Arriving at the Glenmore Hotel on the shores of Big Moose Lake they were now ‘Carl Grahm of Albany and Grace Brown of South Ostelic.’ Now they weren’t even pretending to be man and wife. July 11, 1906 would be the last time Grace Brown was seen alive.

Big Moose Lake was and still is a popular tourist spot. There was nothing unusual about a young couple hiring a boat, cruising round the lake, coming ashore for a picnic and going out on the lake again. Gillette and Grace had done exactly that. Renting a boat from Robert Morrison they’d been seen on and beside the lake before paddling out to one of the lake’s most secluded spots. Again, not unusual for a pair of young lovers perhaps wanting a little privacy.

Numerous witnesses later testified to seeing them and, when they didn’t return at the end of the day, Morrison wasn’t overly worried. He knew that many visitors misjudged the size and scale of Big Moose Lake. They often returned later than planned, sometimes even the next day. Grace Brown and Carl Grahm never returned at all.

The next day a search was organised. Gillette was nowhere to be found, the boat was found capsized and then her body was found at the lake’s bottom. At first it looked like a tragic accident, but not for long.

Carl Grahm was now Chester Gillette again and registered at the Arrowhead Hotel some eight miles from Big Moose Lake. Witnesses later commented on his asking whether there had been any reports of a young woman drowning on Big Moose Lake. News travelling rather slower in 1906 than it does today, nobody had heard anything.

Nor did he seem to them to be in any way distressed or upset. In time his asking about it would raise eyebrows and so would his calm, indifferent demeanour. Gillette’s time would be shorter than he would have believed possible. He had no idea he was already under suspicion.

Once Grace’s body had been identified things moved quickly. Having been found on 12 July she was autopsied two days later. Her body bore injuries consistent with heavy, repeated blows from a blunt object, not injuries typical of someone falling or jumping out of a boat on a calm lake. District Attorney George Ward was suspicious almost from the beginning.

He quickly established who she was and that she worked at Gillette’s Skirt Factory in Cortland. They also discovered her rocky relationship with Gillette courtesy of an unexpected encounter with Bert Gross, a Gillette’s employee.

By the time Ward and his men were en route to Big Moose Lake local newspapers were already reporting a drowning. At Utica railroad station Ward was accosted by Gross and he had plenty to tell them after reading one of the local newspapers. He knew of Gillette’s troublesome history with the dead woman. He also gave them a description of Gillette very closely matching that of the mysterious Carl Grahm. Gillette’s Skirt Factory had received a postcard from Gillette asking them to forward some of his pay to Eagle Bay, said Gross. Eagle Bay was close to Big Moose Lake and that $5 was to cost Gillette dearly.

Not finding Chester Gillette or Carl Grahm on any hotel register in Eagle Bay Ward talked to the local postmaster. The postmaster told him he’d received a brief note asking him to forward any mail to a Chester Gillette at the Arrowhead Hotel in the nearby town of Inlet. They walked into the Arrowhead just as Gillette was walking out of the dining room after breakfast.

Ward immediately began firing questions at him. Gillette in turn couldn’t provide satisfactory answers. Knowing that Grace had suffered a beating before supposedly drowning accidentally while Gillette was with her, Ward immediately arrested him. The hunt was over almost before it began. One of New York’s most widely-reported murder cases was about to begin.

Grace had forwarded her baggage to the town of Old Forge and, when found, it contained numerous letters detailing her troubles with the prime suspect. Gillette now made a decision foolish even by his own standards. Visit Cortland, he told them, where they would find all her letters to him. Under questioning he also admitted having known of her death and that she’d drowned accidentally.

Ward didn’t believe him. He already knew about Gillette having travelled light and that the tennis racket had mysteriously gone missing. Ward believed firmly what his suspect had used it for although it hadn’t yet been found. Gillette was held at the same Herkimer County as Roxalana Druse. When the tennis racket was found buried on the shore of Big Moose Lake, broken as though it had repeatedly struck a solid object, Gillette’s race was run. Arrested in July he was indicted in August. The charge was first-degree murder. Game, set and match to District Attorney Ward and Deputy Sheriff Austin Klock.

Gillette’s trial began at the Herkimer County Courthouse on 12 November 1906 with Judge Irving Devendorf presiding. District Attorney Ward led the prosecution and Gillette was represented by court-appointed lawyers Albert Mills and Charles Thomas. Without the funds to hire his own lawyers and without the help of his wealthy Uncle Noah, Gillette was on trial for his life. If Gillette was superstitious then venue was an ill omen. It was where Roxalana Druse had been condemned to die.

The prosecution case was entirely circumstantial apart from one factor, but Ward pressed it vigorously. Gillette’s tennis racket had been found broken and useless. He’d used several aliases ensuring their initials matched the ones on his suitcase. As it was obvious from the beginning he didn’t intend to and their relationship had broken down, why did he invite her to a secluded place where she then died?

He’d also changed his story. First he’d said Grace died accidentally before saying she’d taken her own life because he wouldn’t marry her. According to Gillette it wasn’t an accident at all, now it was suicide:

“We talked a little more, then she got up and jumped in the water, just jumped in.”

That didn’t explain her serious head injuries, Gillette’s numerous aliases, why he taken her out on the lake or why he hadn’t immediately alerted the authorities to her apparent suicide. He didn’t help his own case by adopting the same calm and unruffled demeanour at his trial as he’d had at the Arrowhead Hotel. The jury weren’t impressed and nor was District Attorney George Ward:

Some of the letters between the two were also entered into evidence. They were also circumstantial evidence, but they did prove Gillette had a motive for murder. Ward had also assembled numerous witnesses who could describe the couple’s movements on their final holiday. Gillette’s prosecutor could prove motive and opportunity. Gillette’s broken tennis racket, Ward argued, was the means.

The letters proved especially damaging, showing as they did Gillette’s motive and proving he’d taken Grace to the crime scene. They also showed his coldness t0o her and his manipulative ways. In response to Grace bringing up his alleged infidelity and suggesting she should stay at the family farm and never trouble him again he’d responded:

“As to the numerous accusations you make, they are all true, so perhaps I had better not come to visit at all. In fact, I think that could be better for both. I hope you will feel better when you come back, but do not rush your work too hard because of it. Hoping you will understand my reason for writing as I do.”

To paraphrase Gillette: ‘Don’t bother coming back. I want nothing to do with you.’ The jury had been unimpressed by Gillette’s manner at trial. The letters only hardened their impression of Gillette as a libidinous moral coward with a motive for murder. Grace’s own words inspired sympathy for her and a stern distaste for her errant boyfriend. Before leaving on her final journey she’d remarked on how hard it would be for her to leave everything behind:

“I have been bidding goodbye to some places today. There are so many nooks, dear, and all of them so dear to me. I have lived here nearly all of my life. First I said goodbye to the spring house with its great masses of green moss; then the apple tree where we had our play house; then the bee-hive, a cute little house in the orchard and of course all the neighbours that have mended my dresses from a little tot up to save me a thrashing I really deserved.

Oh dear, you don’t realise what all this is to me. I know I shall never see any of them again, and mamma! Great heavens, how I do love mamma! I don’t know what I shall do without her. She is never cross and she always helps me so much. Sometimes I think if I could tell mamma, but I can’t. She has trouble enough as it is, and I couldn’t break her heart like that.”

Grace’s words damned and doomed Gillette as much as anything in the eyes of the jury. She clearly thought leaving everything behind meant elopement and marriage. Gillette was only counting the days until he could murder her.

Perhaps most damaging of all was proof that Grace really had been pregnant. When Gillette had murdered her he’d murdered their unborn child as well. After three weeks of testimony that same jury would decide Chester Gillette’s guilt or innocence. In doing so they would effectively decide his fate.

On 4 December 1906 they took only five hours. Gillette guilty as charged and didn’t deserve mercy. Gillette’s court-appointed lawyers worked as hard for him as if they’d been drawing huge salaries. They immediately appealed citing DA Ward’s attitude towards their client, that Grace Brown’s pregnancy shouldn’t have been used as evidence, that her letters prejudiced the jury against him and that Ward had summed up the case in terms not supported by the evidence.

Scraping the barrel still deeper, they challenged the right of State Governor Frank Higgins to have convened an extraordinary session of the court to try Gillette. According to them this was unconstitutional and he should have been held until the court’s next regular session. As Gillette’s trial had been conducted outside of the court’s usual schedule, his lawyers argued that it had no right to try him let alone convict him.

New York’s appellate judges disagreed with this distinctly desperate argument. The appeal argued on 9 January 1908 was tersely dismissed on February 18. Chief Justice Frank Hiscock’s opinion was abundantly clear:

No controversy throws the shadow of doubt or speculation over the primary fact that about 6 o’clock in the afternoon of July 11, 1906, while she was with the defendant, Grace Brown met an unnatural death and her body sank to the bottom of Big Moose Lake.

Chester Gillette was also going to suffer an unnatural death in Auburn Prison’s electric chair. His date was 30 March 1908, barely two weeks after his appeal was so bluntly rejected. Charles Hughes had replaced Frank Higgins in the Governor’s chair on January 1, 1907. Serving until 6 October 1910, Hughes wasn’t in merciful mood.

Starting with George Granger on 25 February 1907 and ending with Giuseppe Gambaro on 25 July 1910 Gillette’s was the ninth of thirty-seven executions during Governor Hughes’s tenure. They included Mary Farmer, only the second woman in New York to be electrocuted. Gillette’s lawyers held little hope of clemency and rightly so. When a personal appeal from Gillette’s mother failed all was lost.

When the time came at dawn on 30 March 1908 Gillette walked his last mile calmly, showing as much emotion as he had at the Arrowhead Hotel two years before. According to an Associated Press report:

‘He went to his death in the electric chair at Auburn Prison without a sign of weakness and with the same lack of emotion which has characterised him from the day he was arrested and charged with the crime.’

Reverend Henry McIlravy and Auburn’s resident Chaplain Cordello Herrick tacitly stated afterward that Gillette had confessed his crime shortly before dying:

“Because our relationship with Chester was privileged, we do not deem it wise to make a detailed statement and simply wish to say that no legal mistake was made in his electrocution.”

McIlravy had shown considerably more emotion than Gillette himself. After Davis threw the switch he was overcome by the sight of Gillette’s body straining against the chair’s heavy leather straps. Traumatised by the experience, Mcilravy had to be led out of the death chamber by a prison officer.

For a man who’d once disdained religion while his parents embraced it, Gillette found the faith he’d always lacked. His final statement before dying exhorted young men to disdain his loose morals and embrace a Christian existence, not the life Gillette himself had led. Part of it read:

“In the shadow of the valley of death, it is my desire to do everything that would remove any doubt as to my having found Jesus Christ, the personal Saviour and unfailing friend. My one regret, at this time, is that I have not given him the pre-eminence in my life while I had the opportunity to work for Him.”

Was he sincere? Or was he holding some shred of hope that Governor Hughes might be convinced and stay the hand of Edwin Davis? Either way it did no good. Chester Gillette had gone to join the ghosts of many other condemned prisoners and, more importantly, their victims.

Chester Gillette and Grace Brown were now gone, but not forgotten. Their case inspired books, films, plays and songs still sung today. They also provided New Yorkers with one of the early 20th century’s most memorable murder cases. Theodore Dreiser’s book An American Tragedy was and remains an American classic.

The Arrowhead Hotel where Gillette was so speedily run to earth is also gone. Built in the 1890’s by Fred Hess the original Arrowhead was destroyed in a fire in 1913. Today the Arrowhead Park, visitors enter it driving past the hotel’s original stone towers. According to Google Maps satellite imagery they also drive past an ironic reminder of Gillette’s brief stay there.

Left of Arrowhead Park Road resides a pair of tennis courts.

Gillette and fifteen other historic New York cases can be found in my book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York,’ published by Fonthill Media and America Through Time.

Leave a Reply