“Yes, they are killing me.” – Joe Arridy, when asked by Warden Roy Best if he understood why he was about to step into Colorado’s gas chamber.

It’s rarer than it used to be that a case affects me as much as this one. If you cover true crime for a living then you learn to keep perspective and some distance between yourself and your subject matter. But, every now and then, you find a story that to some degree bridges that distance, a brutal reminder that true crime is about real people with real lives undergoing real suffering.

Joe Arridy’s is one of them. He was as much a victim as anybody

Arridy was born April 15, 1915 in Pueblo, Colorado to non-English-speaking Syrian immigrants, just another boy of immigrant stock or so he seemed at first. Unfortunately (and perhaps fatally, as we shall later see) Joe suffered from substantial mental impairments. He had a mental age of six in the body of a 24-year old man when he was arrested, charged, tried, condemned and ultimately gassed. Today Colorado authorities openly admit he was wrongly convicted and executed for a crime he did not commit.

He was illiterate and possessed an IQ of only 46. He was even removed from the first grade of elementary school after the headmaster decided he was incapable of being educated. In the official language of the time Joe was listed as an ‘imbecile,’ slightly less impaired than an ‘idiot’ but more impaired than a ‘moron.’ Diagnostic definitions at that time really were that insulting, but labels didn’t really matter. Joe Arridy was still a boy in a man’s body. A mental age of six left him far too vulnerable to function adequately by himself.

At age 10, Joe was committed to the Colorado State Home and Training School for Mental Defectives in Grand Junction. Tests confirmed previous assessments of his intellectual abilities (or lack thereof). He was unable to repeat a simple one-digit number. When shown colour cards Joe claimed that red was black and green was blue. His conversation was no better, being able to communicate in sentences of two or three words and seldom fluently even then.

Missing Joe terribly, his father brought him home again after nine months at Grand Junction. Joe spent the next three years uneducated and seemingly impossible to educate. His days largely consisted of taking long walks around the local area, almost always alone. With a mental age of six he was also highly vulnerable to exploitation, as was proved when he was discovered by a probation officer being sexually abused by a group of other boys. A court order was obtained returning Joe to the State Home.

Joe spent another seven years at the home, being considered incapable of independent living. Staff regarded him as incapable of either work or education. Given that his concentration wandered and he grew tired easily Joe was given ‘day activity’ helping one of the kitchen workers. She described him simply:

“He depends on others for leadership and suggestion.”

What was about to happen would prove her right to an appalling degree. ‘Others’ would ‘suggest’ him into Colorado’s Death Row at Canon City Prison, into a tiny cell near what locals called Woodpecker Hill. They would later lead him up Woodpecker Hill and straight into Colorado’s gas chamber.

In 1936, at age 20 in body and still only six in mind, Joe meandered away from the home with several other boys. They went to Pueblo, riding railroad boxcars. He was last seen in Grand Junction on the evening of August 13, 1936 and not seen again until he staggered into a hut occupied by railroad workers in the East Railroad Yards of Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Meanwhile, on August 15 shortly before midnight, Pueblo sisters Dorothy Brain (age 15) and Barbara (age 12) were attacked in their bedroom while sleeping. Barbara survived her near-fatal beating. Dorothy didn’t survive, having been raped as well as bludgeoned. Barbara would later identify Mexican transient Frank Aguilar, but never identified Joe Arridy.

Joe was arrested on August 26 by two railroad detectives and Pueblo Sheriff George Carroll who, like other local lawmen, was busily detaining and questioning potential suspects in the Brain attacks. After only 90 minutes of questioning, Carroll called a local reporter claiming to have successfully captured the Pueblo killer, that Arridy had confessed, had said he was acting alone, and had admitted using a club to attack the Brain sisters.

All of which was news to Pueblo’s Chief of Police, one J. Arthur Grady. He was more than slightly stunned as he had already arrested the actual murderer. Frank Aguilar, a former Works Progress Administration (WPA) worker who had once been supervised by the Brain sisters’ father, was already in Grady’s custody awaiting further questioning. How Sheriff Carroll could have the killer under lock and key was a mystery. It would later be proved no mystery at all. Carroll deliberately railroaded Joe Arridy to the gas chamber.

Police soon found the murder weapon, a hatchet head with nicks on the blade corresponding with the injuries suffered by the Brain girls. It wasn’t a blunt object like the club Carroll claimed Arridy had admitted using. Carroll interrogated Arridy again, calling reporters to say that, this time, Arridy had admitted using a hatchet head and had remembered (conveniently) that he hadn’t been alone and may have committed the crime with what Carroll referred to as ‘others.’

It was easy for Carroll to change his story. Easy because there were no records of Arridy’s alleged confessions. There were no written records, quotes, witnesses, transcripts or audio recordings. Nothing to say that Carroll was lying or that Arridy was telling the truth. Carroll constantly discussed the case with reporters and testified in court entirely from his (highly suspect) memory.

Aguilar went on trial on December 15, exactly four months after the attack on the Brain sisters. He was on trial for a near-identical attack on elderly Pueblo women Sally Crumply and her niece R.O. McMurtree (who survived and testified against him). It lasted a week before Aguilar was convicted and condemned to die. He was transported under armed escort to Canon City Prison and a Death Row cell on Woodpecker Hill. He was already there when Joe Arridy went on trial for attacking the Brain sisters, an attack he had already admitted and that Arridy would ultimately pay for with his life.

Meanwhile, Carroll had taken over the Brain investigation. When Aguilar was brought to witness the re-enactment of the Brain attacks Carroll was present. Aguilar also gave a signed confession that mysteriously never saw a courtroom before Aguilar retracted it. Equally mysterious, it still made the pages of the Pueblo Chieftain (a newspaper still in publication today) and did Carroll no harm whatsoever. It helped kill Joe Arridy.

In pre-trial hearings Carroll took the stand on five separate occasions and was allowed to run riot. He claimed Arridy was a perfectly normal young man (he obviously wasn’t). According to Carroll the defendant was articulate and spoke in normal, clear sentences (he didn’t, and couldn’t). Carroll swore blind that Arridy could accurately distinguish the colours of the bedroom walls where the attack happened and the victims’ nightshirts. The same nightshirts had been forensically examined and matched to fibre samples found under Aguilar’s fingernails, but Carroll neglected to mention that fact.

Psychiatrists could well have saved Arridy from even going to trial, never mind facing execution, if they’d certified him insane. Instead they dodged the question. They admitted he didn’t know right from wrong but refused to agree that he was insane under the law. In their opinion, for a person to have gone insane then they must have been sane at some point in the past. In their opinion Arridy had never been normal in the first place.

At trial his defense was weak, almost non-existent. His lawyers offered no evidence, choosing only to cross-examine prosecution witnesses. Given Carroll’s high jinks that should still have been enough, but it wasn’t. Arridy was poor, lacked the intellect to realise what was happening and could do virtually nothing to aid his own defence, pathetic though that defence was. He was convicted on April 17, 1937 and transported to Death Row. With bitter irony he was a few cells away from Frank Aguilar who was still awaiting his evening stroll up Woodpecker Hill.

Four months later, on August 13, Aguilar took his evening stroll, briefly checking into what Colorado convicts called ‘Roy’s Penthouse.’ He died quickly, Colorado having largely mastered the new method since the chamber’s installation in 1936. With him probably went Arridy’s last hope of survival. On the same day as Aguilar entered Colorado’s ‘coughing box’ Carroll and the two railroad detectives received a $1000 reward for Arridy’s capture. They’d shown themselves to be railroad detectives in every sense.

A new lawyer bought Arridy time as he awaited execution. Gail Ireland (later Colorado Attorney General) fought his case for free, winning nine stays and taking his case right to the US Supreme Court. Meanwhile, her client became the most popular inmate on Death Row. Quiet and child-like, he passed his days playing with toys like any other six-year-old might do. His playthings included a toy car given him by the Warden’s son. From Warden Roy Best himself came Joe’s favourite toy, a train set. On the eve of his execution he would give it to another inmate.

Warden Best was an old-school prison Warden. He was fair, but ran Canon City with an iron fist. That fist swung hard at staff and inmates alike if they defied him or otherwise didn’t conform to his rules and standards. In In the 1950’s when most prisons had abandoned corporal punishment he faced trial himself for personally flogging inmates who had attempted escape.

Tough enough to be respected by staff, inmates and population of Colorado, Best could be brutal by today’s standards. He was also human enough to see the patent injustice of what was about to happen. In Arridy’s case he was as sympathetic as any Warden could be, but that changed nothing. Regardless of his personal feelings Best still had a job to do and that meant executing Joe Arridy like any other condemned inmate.

Arridy himself seems to have known he was there to die without ever really understanding what death actually was. No surprise considering he was a child in a man’s body, but that didn’t make the prison staff’s job any easier. As time wore on and eventually ran out their lives only became more difficult. To Arridy the gas chamber was simply an object and death was something he simply couldn’t comprehend. When he arrived at Canon City, somewhere most convicts hated and feared, he had little idea why they would. On being told he was there to be executed he responded with “Oh no, Joe won’t die.”

Of course, he would die. After nine stays of execution and with the Governor refusing to intervene, Gail Ireland could do no more. The State of Colorado was determined to have its pound of flesh. Freeing or exonerating Arridy would raise questions about his interrogation, trial and guilt and the closer Arridy’s date became the more questions would be asked. Commuting his sentence would have severely dented the Governor’s electoral prospects. Colorado seemed more interested in playing politics and preserving the ‘infallibility’ of its laws and penal system than in justice or saving Joe Arridy’s life.

On January 6, 1939 Joe was given the last meal of his choice, a simple dish of ice cream. He was escorted by Warden Best and around 50 other people to Colorado’s silver-painted gas chamber, given the Last Rites by a Catholic priest and stripped to only his shorts. On his way to the gas chamber he gave away his toy train. Outside the chamber Warden Best read the death warrant and asked him if he knew what was happening. Joe’s response was both child-like and chilling:

“Yes, they are killing me.”

Almost naked he was seated in the chamber. Guards worked quickly to buckle the restraining straps and connect a special stethoscope leading outside the chamber. It was then that he became scared. He was gently pacified by Warden Best holding his hand and talking soothingly to him. It was a bitter irony that Best, the man who oversaw Arridy’s execution, probably showed him greater kindness than the rest of Colorado’s justice system. With Arridy now calmer a blindfold was placed over his eyes. The airtight steel door was shut and sealed.

Standing near the chamber with tears in his eyes Warden Best gave the signal and the lever was pulled. Dilute sulphuric acid mixed with sodium cyanide, forming almost-invisible vapours that rose from under the chair around Arridy. Best, tearful as the execution began, now sobbed openly as the gas took effect and Arridy died. The end was mercifully brief, Joe being unconscious within two minutes and certified dead within ten.

Attorney Gail Ireland had been blunt before Joe Arridy’s unjust execution, stating:

“Believe me when I say that if he is gassed, it will take a long time for Colorado to live down the disgrace.”

It did take a long time but, days before leaving office, 72 years and one day after Joe’s death, outgoing Governor Bill Ritter issued him a pardon on January 7, 2011. As he put it:

“Pardoning Mr. Arridy cannot undo this tragic event in Colorado history. It is in the interest of justice and simple decency, however, to restore his good name.”

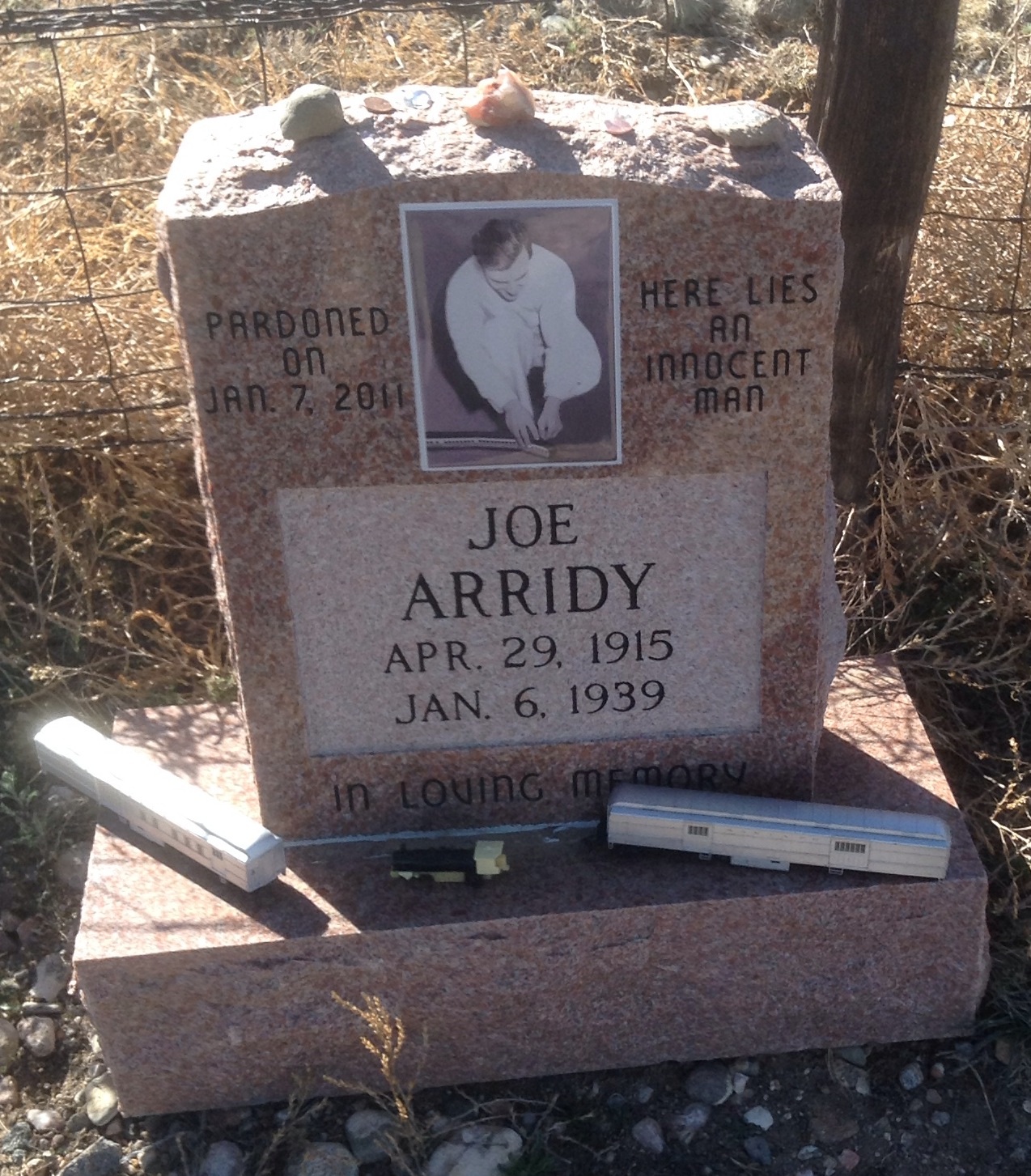

It would be hard to argue with that. Joe Arridy is one of the few inmates on Woodpecker Hill to have a proper tombstone. It bears his name, dates of birth and death and a haunting message:

‘Pardoned on Jan. 7 2011. Here lies an innocent man.’

Leave a Reply