Your cart is currently empty!

Rufus ‘Whitey’ Franklin, the incorrigible’s incorrigible.

Today, Rufus Franklin (‘Whitey’ to his friends) is a name largely forgotten. In the South during the 1930’s Franklin was a crook well-known the South’s law enforcement and penal system alike. Born in Alabama in 1916 Franklin was the incorrigible’s incorrigible, a crook so dedicated he would likely have never gone straight even if pardoned…

Today, Rufus Franklin (‘Whitey’ to his friends) is a name largely forgotten. In the South during the 1930’s Franklin was a crook well-known the South’s law enforcement and penal system alike. Born in Alabama in 1916 Franklin was the incorrigible’s incorrigible, a crook so dedicated he would likely have never gone straight even if pardoned for his laundry list of crimes. Two in particular stand out, his attempted escape from Alcatraz in May 1938 and the crime that sent him to the dreaded Rock in the first place.

By 1933 Franklin was uncomfortably ensconced in Alabama’s fearsome Kilby Prison for armed robbery and murder. He had already been fined for trespassing in Mississippi, served time for car theft in Florida, been on two Alabama chain gangs for loitering and larceny and been jailed in Tennessee for carrying a gun. Kilby was already one of the worst prisons in the country, but Franklin was still luckier than he might have seemed.

At the time Alabama considered armed robbery a capital crime along with murder, rape and several others. Robbery alone could earn felons a seat in Alabama’s electric chair, a brightly-painted throne nicknamed ‘Yellow Mama,’ even if no shots were fired and nobody was harmed. Franklin’s next robbery was in 1936 by which time the 1934 National Bank Robbery Act made bank robbery a capital crime under Federal as well as state law. So, having been sent to Kilby for life in 1933, how was Franklin free to risk Yellow Mama again in 1936?

Simple; Kilby’s Warden had granted Franklin a week’s unescorted furlough to attend his mother’s funeral. To be fair to Franklin he did attend her funeral. He also robbed at least one bank before her funeral and embarked on a three-month crime spree afterward. Franklin had violated his parole in the most spectacular fashion and, surprisingly, a tough-minded Alabama judge chose not to send him to Yellow Mama. Instead Franklin returned to prison with a extra thirty years on top of his life sentence. Kilby’s Warden, rather aggrieved at Franklin’s spectacularly-violated parole, sent him to the Federal penitentiary in Atlanta. After another escape attempt Atlanta’s Warden sent him to the one place thought able to hold him – Alcatraz.

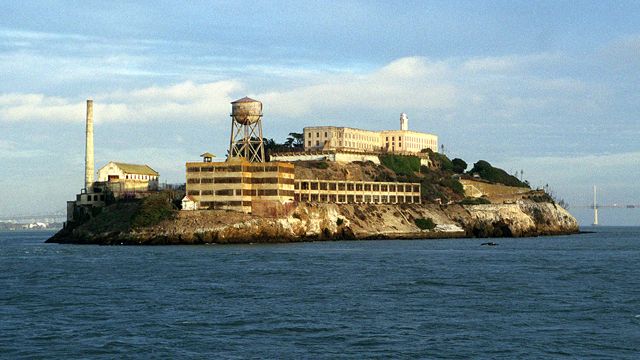

The Rock had opened in August 1934 as America’s first supermax prison, a warehouse designed to hold the worst of the worst, those deemed irredeemable and incorrigible. It’s not hard to see how Franklin fit that particular description. While Kilby (and Southern prisons generally) had long been known for physical brutality Alcatraz broke its prisoners differently. Rather than attack a convict’s body they aimed to break his mind with a regime custom-made to crush even the most rebellious spirit.

Work, a standard practice at other prisons, had to be earned on the Rock. At least three months had to be served without a disciplinary infraction before a convict could be offered even prison labour. The food was decent, if rather bland and boring. Visitors could only be people with no criminal record subject to an FBI background check. Even relatives and lawyers had to pass one. Visits themselves were always supervised and only one visit per month was granted.

The ‘Silent System was also rigidly enforced. Unless absolutely necessary taking was a breach of discipline punished by solitary confinement and loss of time off for good behaviour. The breaking process even began with the convict’s Alcatraz mugshot. No names are on Alcatraz mugshots, only the convict’s number. It let them know from arrival that regardless of what they had been on the outside, they were nothing inside the Rock. Even the biggest names like Al Capone had no name on their mugshot, only their number.

As rebellious as the prison was restrictive, Franklin was as custom-made for the Rock as it was for him. Arriving in 1936 as inmate AZ-335 it only remained to be seen whether Alcatraz or Franklin would win the battle. It took little time for Franklin to strike the first blow. In May 1938 he teamed up with James ‘Tex’ Lucas and Thomas Limerick to break out in the Rock’s third escape attempt. It almost cost Franklin his life.

May 23, 1938 saw Franklin, Limerick and Lucas fatally beat Guard Royal Cline with a hammer before climbing to the roof of the main cellblock intending to reach San Francisco Bay and swim to the mainland. The attempt failed miserably and bloodily. Tower guard Harold Stites caught them in his sights, fatally shooting Limerick and seriously wounding Franklin on the roof. Stites would figure again in Franklin’s story, but not until May 1946.

Franklin and Lucas, both career felons with violent records, miraculously escaped the death penalty. Franklin seemed to have a charmed life having escaped both Kilby’s electric chair and now San Quentin’s gas chamber. It would prove a even more restricted life. With an additional life sentence he now held a dubious record, having more unserved prison time than any other Alcatraz inmate. He would spend most of his time at Alcatraz in the worst cells the prison had to offer, the solitary confinement unit in D Block.

Not until 1948 would Clarence Carnes earn more time than Franklin for his part in the Battle of Alcatraz, a spectacularly-bloody escape attempt in in May 1946. Before Carnes, a violent, aggressive young Oklahoman known as the ‘Choctaw Kid,’ Franklin had set the bar. By then Franklin had spent years in the Rock’s solitary confinement cells on D Block. D Block was the worst place on Alcatraz. Some cells were similar to those of the general population with open-front barred doors and cramped space.

Others were known as the Dark Hole or simply ‘The Hole.’ These had a bare concrete floor, no bed, a bucket for a toilet and were kept in total darkness. They were also draughty, damp and often freezing cold. Franklin had seen his fair share of both types of cell and hadn’t liked either. His friend Joe Cretzer, a former bank robber, escaper, killer and once one of California’s most wanted, had teamed up with Kentucky bank robber Bernard Coy and others for a mass escape attempt and had decided to bring Franklin with them. Cretzer’s failure to free Franklin was important in the 1946 attempt’s failure and perhaps cost Cretzer his life. It probably saved Franklin’s.

When Coy, Cretzer, Carnes, armed robber Marvin Hubbard, the mentally-ill Sam Shockley and Texas cop-killer Miran ‘Buddy’ Thompson took over D Block, Cretzer wanted Franklin’s dark cell opened. When told opening the cell would trigger an alarm and alert prison authorities, Cretzer decided to leave the most skilled lock-picker and burglar on the island in his cell. When using the wrong key on the door between the main cellblock and exercise yard jammed the lock Franklin might have been able to save the situation. Still sat in his dark cell he could do nothing when the prison erupted in a three day orgy of blood-letting and brutality.

By its end Cretzer, Coy and Hubbard were dead and over a dozen guards and convicts had been injured. Along with Coy, Hubbard and Cretzer were two Alcatraz guards, William Miller and Harold Stites. Just as Stites had killed Thomas Limerick and seriously wounded Franklin in 1938, Franklin’s friend Cretzer had killed Stites in a pistol duel. At their trial Carnes would earn earn enough extra prison time to shatter Franklin’s record. He was only spared the death penalty because he was nineteen at the time and had tried to talk Cretzer and the others out of trying to murder several guards they had taken hostage.

Thompson and Shockley were not so lucky, going to San Quentin’s gas chamber in December 1948. On the execution team was Lieutenant Philip Bergin, a senior Alcatraz guard. Bergin reported Thompson as giving him a wan smile while being strapped into one of the chamber’s two chairs. He saw Shockley spit in a guard’s face at the same time. Minutes later they were dead. By then Franklin was still in D Block and would stay there for years to come.

When Franklin had arrived on Alcatraz in 1936 he had to wait until at least 1966 before being eligible for parole. Even then he could have been re-arrested and returned to Alabama to serve out his unexpired time there. Leaving Alcatraz for Leavenworth and then Atlanta, he remained behind bars until 1974. He was only released then because he was dying. Released on compassionate grounds Franklin had spent all but a few months of his adult life in prison. Only months after his release Franklin was dead. He died in Dayton, Ohio in May, 1975. He was only fifty-nine years old.

The story of the ‘Battle of Alcatraz’ can be found in my second book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in Northern California.’ My first book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York‘ is also currently on sale.

One response to “Rufus ‘Whitey’ Franklin, the incorrigible’s incorrigible.”

-

Harold Stites was killed by a friendly-fire, not by Cretzer. 😉

Leave a Reply