Your cart is currently empty!

July 2, 1962 – Crash-out on Condemned Row (Almost).

July 2, 1962 was supposed to be a quiet day on San Quentin’s Condemned Row. Securely lodged on the top floor of North Block, California’s condemned were expecting a summer’s day as bleak, depressing and dull as any other. So were the Condemned Row officers whose job it was to keep them under control. With…

July 2, 1962 was supposed to be a quiet day on San Quentin’s Condemned Row. Securely lodged on the top floor of North Block, California’s condemned were expecting a summer’s day as bleak, depressing and dull as any other. So were the Condemned Row officers whose job it was to keep them under control. With a few dishonourable exceptions, they were wrong.

Almost a month had passed since multiple murderer Henry Busch had been handcuffed and led from his cell to the secure elevator that ran only between Condemned Row and the ground floor. On the ground floor a seat in one of two cells awaited Busch, known as the ‘Ready Room.’ There Busch spent his last night on Earth under constant observation, separated from his fate by only a steel door and a dozen footsteps.

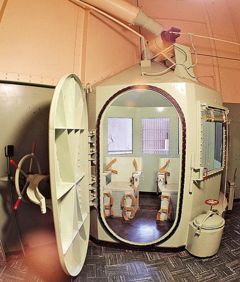

His fate, of course, was San Quentin’s gas chamber. Installed in 1937 and first used in 1938, it had long been known by a variety of grim nicknames. Painted apple green throughout, it was the ‘little green room’ to some, to others the ‘smokehouse,’ ‘Time Machine’ or ‘coughing box.’

When his time ran out, Busch was given a pair of jeans and a white shirt. A specially-designed stethoscope was placed over his heart, connected to another stethoscope outside the chamber via an airtight link. When the cyanide eggs dropped into dilute sulphuric acid under one of the chamber’s two steel chairs Henry Busch would choke, struggle, convulse and black out. When the prison doctor removed the stethoscope from his own ears, Henry Busch was dead.

Years earlier, Warden Clinton Duffy had unwittingly bestowed the name that would become part of poplar culture, ‘The Big Sleep.’ A convinced abolitionist and veteran of Condemned Row, Duffy had overseen the executions of 88 men and two women. He had loathed the gas chamber as much as the gallows that had preceded it, but still had to oversee them. It was not a task he relished.

Most denizens of Condemned Row passed their time quietly, preferring to avoid causing trouble. Some wanted to avoid antagonising the courts or the Governor while their cases were still in pay. Others, more literate and perhaps more intelligent than others, were doing their own legal work. Unwilling or unable to afford top-flight lawyers, they fought for their own lives and had little time or energy for causing needless aggravation.

Unlike the majority of their peers, those dishonourable exceptions had no intention of waiting on appeals, stays of execution or the Governor’s mercy. With their time short and getting shorter by the day they would attempt the near-impossible. Motivated by desperation more than any realistic chance of success, they would try to break out of Condemned Row.

All of the would-be escapers had been convicted of murder and none could realistically expect mercy. Willard Winhoven had arrived two years earlier having previously served twelve years on Alcatraz after escaping from Leavenworth in January, 1947. Winhoven had unwittingly helped Alcatraz escapers Frank Lee Morris and John and Clarence Anglin. A convict electrician on the Rock, Winhoven had removed a fan motor in 1957 from the vent shaft used by Morris and the Anglins to reach the cellhouse roof only weeks before Winhoven tried to escape Condemned Row.

David Bickley had arrived relatively recently. Convicted of murder during an attempted robbery of the Gold Room Bar in Long Beach in January, 1961, Bickley had drawn a death sentence for the murder of Elvin Lloyd Feightner. His crime partner John Larue Young had drawn a life sentence. Bickley may have thought that was unfair, but so far the courts and Governor had begged to differ. His latest appeal had been denied on June 4, 1962, two days before Henry Busch had walked his last mile.

Clyde Bates and Manuel Chavez were also fairly recent arrivals with equally limited hopes of mercy. Convicted of arson resulting in the deaths of six people and serious injury to a number of others, they had arrived on Condemned Row after torching a bar in 1957. They had occupied themselves filing appeal after appeal, so far without success. Having murdered ix of his constituents they lacked faith in the Governor feeling especially merciful.

Last and most notorious were Augustine Baldonado and Louis Moya. Convicted with Elizabeth Duncan in March, 1959 for murdering her daughter-in-law Olga in November, 1958, they had testified against her in the hope of mercy then pled guilty to first-degree murder believing they would draw life sentences. They were wrong.

Without a formal plea agreement in place (they had neglected to secure one), the judge was under no obligation to show mercy and hadn’t. To their surprise and fury, they were sent to Condemned Row and their executions had been set for August of 1962. Their time was fast running out. In Condemned Row parlance they were ‘short’ and they knew it. Any chance, no matter how slim, was better than nothing.

Their plan, such as it was, was a simple one. Grab a guard or two as hostages, steal the keys to Condemned Row’s doors and elevator, ride down and use their hostages as human shields to walk right out of the front gates to freedom. It was simple, relatively easy to enact and had only one small technical hitch.

The guards on the Row itself didn’t have the keys they needed for security reasons. It was and still is policy at San Quentin that hostages are never traded for the release of prisoners regardless of the risk to hostages themselves. It was doomed from the start, but so were the prisoners and that made it worth a shot, at least to them.

Roy Kardell and C.L. Deatrick were the unlucky guards on duty. Deatrick had responded to a phone call from Kardell who was on Condemned Row duty at the time. Deatrick had been quickly subdued and his revolver and shotgun seized by the prisoners. Now they needed the keys. They wouldn’t get them. Worse still, Associate Warden Dale Frady and Warden Fred Dickson were in no mood to break policy and trade Kardell and Deatrick for the escape of six condemned murderers. They also responded quickly, and in force.

Kardell and Deatrick had been grabbed at just after 1am. Before 3am Associate Warden Louis Nelson led a dozen guards to a ledge opposite the Condemned Row cells. A barrage of tear gas bombs quickly filled the Row with a less lethal, but no less unpleasant form of gas that soon had other condemned prisoners pleading with their would-be escapers to surrender. It was also made clear that Kardell and Deatrick were never going to be traded for freedom.

By 4:15am it was all over. Far from marching boldly out of the front gate, the six were all back under lock and key having been disarmed and subdued. The tear gas barrage had caused other prisoners to offer a deal of their own; Stop firing the gas and the condemned six would release their hostages and surrender their weapons. The crisis, unlike the bloody ‘Battle of Alcatraz’ in May, 1946, had been resolved without loss of life.

Two prisoners, Miran Thompson and Sam Shockley, had been executed in San Quentin’s gas chamber in December, 1948 for their parts in the Alcatraz break-out. Two of the San Quentin Six soon would be. On the afternoon of August 7, 1962 they were led to the locked elevator they had tried to reach a month earlier. Down to the two ‘Ready Room’ cells they went while Elizabeth Duncan was being brought from her cell in the women’s prison at Corona.

At 1pm on August 8, Baldonado and Moya sat side-by-side in the twin perforated steel chairs. Duncan had gone before them at 10am. Left to steep in the cyanide fumes for an hour, the chamber had been cleaned and prepared for her confederates. All three died quietly and without further trouble. Ironically, they were the only two of the San Quentin Six to do so. None of the other four were executed.

That did not mean that nobody else walked San Quentin’s last mile. After Moya and Baldonado in 1962 some of those who had pleaded with them to surrender found their own time had run out. Lawrence Garner went downstairs on September 4, only a month after Duncan, Baldonado and Moya. After Garner went Melvin Darling on October 2, 1962.

November 21 of that year saw the departure of Allen Ditson via the ‘little green room’ with James Abner Bentley following him in January, 1963. Bentley was also facing murder charges in Oklahoma but whether it was San Quentin’s ‘smokehouse’ or Oklahoma’s electric chair (the charmingly named ‘Sizzlin’ Sally’) made no difference. After cop-killer Aaron Mitchell, dragged screaming into the chamber on April 12, 1967, the ‘Big Sleep’ would sit idle until Robert Alton Harris in 1992.

One response to “July 2, 1962 – Crash-out on Condemned Row (Almost).”

-

I am a person who believes in the death penalty in certain cases. Like murder of children, women, Serial Killers. Overall I think America has the right idea. Bring back the Gallows, Gas Chamber, and Electric Chair. Overall I believe in the Gas Chamber slow and painful

Leave a Reply to Bill McbrideCancel reply