Your cart is currently empty!

Dallas Egan, a half-pint of whiskey (to the last drop).

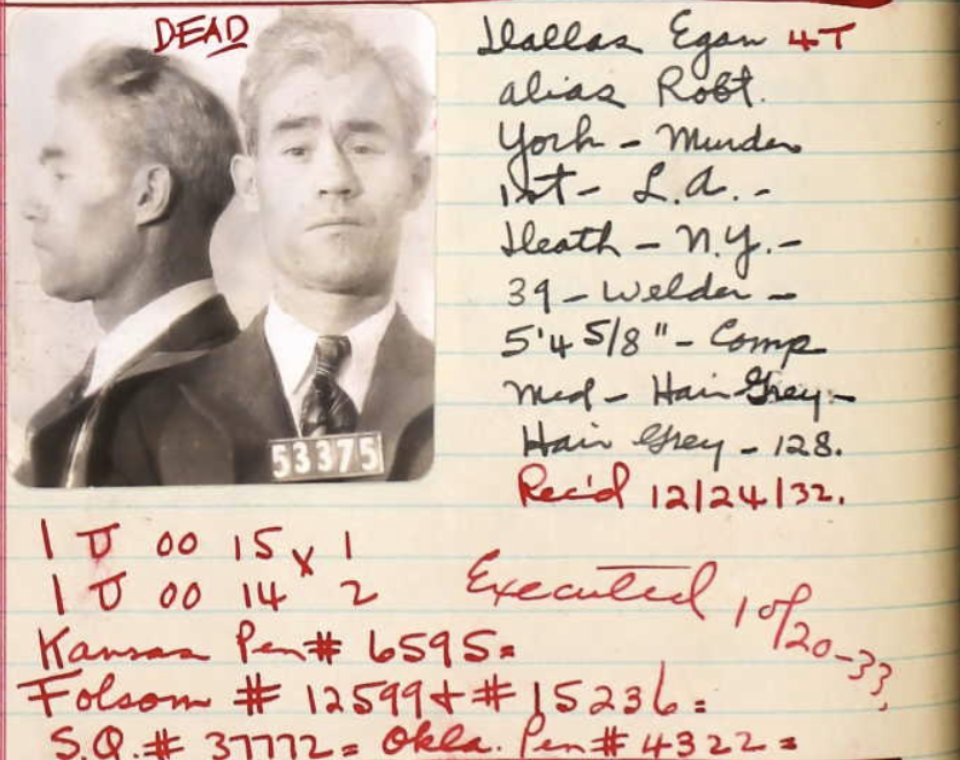

Armed robber and murderer Dallas Egan was rather younger than Gardner when he died on the gallows in San Quentin’s ‘Hangman’s Hall.’ Courtesy of Governor James ‘Sunny Jim’ Rolph, Egan may well have been drunk as well. It was by Rolph’s order that Egan was plied with whiskey before his execution and it had…

Armed robber and murderer Dallas Egan was rather younger than Gardner when he died on the gallows in San Quentin’s ‘Hangman’s Hall.’ Courtesy of Governor James ‘Sunny Jim’ Rolph, Egan may well have been drunk as well. It was by Rolph’s order that Egan was plied with whiskey before his execution and it had been Egan’s last request.

Granting Egan’s request mattered more to the Governor than breaking the law. Prohibition would not be repealed until 5 December 1933. Egan’s date with the hangman was 20 October, months earlier. Rolph’s order to San Quentin’s Warden had been clear; Give Egan as much whiskey as he could stand. As Rolph himself remarked “We would be pretty small when we sent a man into Eternity if we could not grant his last request.”

Rolph’s attitude to Prohibition was always openly contemptuous. Mere months after Prohibition had come into effect he had ordered an entire boxcar of whiskey, passing out bottles at that year’s state Democratic convention to delegates and reporters alike. When Egan met the hangman, Governor Rolph still basked in the nickname ‘Sunny Jim.’ He was yet to acquire the nickname ‘Governor Lynch.’

That title wasn’t bestowed until Brooke Hart’s kidnapers were lynched in San Jose in late-November of 1933. Rolph’s public support for the lynching of Thomas Thurmond and John Holmes earned him lasting contempt in California and further afield, but that was of no consequence to Egan. He was long dead. By the time Rolph publicly endorsed the lynching and offered to pardon anyone convicted of taking part Dallas Egan was virtually forgotten.

Egan’s crime had been a particularly senseless one. The Broder jewelry store in Los Angeles was typical of its type with rich pickings for a troupe of armed robbers. Recently paroled from Folsom, Egan had assembled a motley crew and together they had already committed several robberies. They were an experienced gang who knew the drill and the risks. They still took them regardless of the outcome.

Egan’s motley crew of four other felons (Rogers, Turcott, Alvarado and Johnson) were experienced crooks, but had reckoned without Egan’s willingness to kill even when it wasn’t strictly necessary. His needlessly shooting Michigan tourist William Kirkpatrick caused outrage among Californians. Even if Egan himself had any desire to live an acquittal or reprieve was probably out of the question.

The Bureau of Water and Power, Lakeville Creamery and Los Angeles Gas Electric Company had already played host to Egan’s gang and Broder’s would have been just another job. With two men including the getaway driver outside and three entering Broder’s it should have been one of their easier robberies. Instead 23 July 1932 turned out to be Egan’s death knell.

On vacation from his hometown of Battle Creek, Michigan, William Kirkpatrick was seventy-six years old and profoundly deaf. He also happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, right outside Broder’s when Egan’s gang were robbing it. Not hearing anything suspicious he fished his watch out of his pocket. Kirkpatrick wasn’t doing anything to obstruct the gang, he was about to check his watch against the store’s clocks when the gang were leaving and posed no threat whatsoever. Had either of the two men outside done their job and kept bystanders away there might not have been a murder at all. Unfortunately they were not, and there was.

Being profoundly deaf Kirkpatrick never heard Egan’s order to go into the store’s back room with the staff and other customers. So far staff and customers had been subdued, the loot was quickly collected and the gang were getting ready to leave when Kirkpatrick made his entrance. Egan supplied his exit with a Springfield rifle.

When Kirkpatrick didn’t instantly obey his orders and then put his hand in his pocket Egan shot him through the head. There had been no need whatsoever for Egan to shoot. With the loot collected and Kirkpatrick dead the gang piled into their car and fled. Despite being followed for five blocks by proprietor Sidney Broder they escaped with a $5000 haul worth almost $100,000 today. While Egan murdering Kirkpatrick had been both deliberate and unnecessary the gang had also made one serious mistake. Regularly using the same car for their robberies meant that police were already on the look-out for a 1929 Oakland Cabriolet.

Described by witnesses as either brown or tan, the car had been seen at several recent robberies and Egan’s gang also foolishly used it as their daily driver. The gang would raid a branch of the Bank of America on 24 August in which Alvarado and Johnson were killed. Partly through public outrage at Kirkpatrick’s needless slaying Egan, Turcott and Rogers were captured shortly afterward.

By his own admission Egan was one of life’s natural criminals. By the time he murdered Kirkpatrick Egan had already served nine years at Folsom and already had four previous convictions. California’s second state prison after San Quentin, Folsom opened in 1880 and quickly became legendary for harsh conditions and harsher discipline. Life in its general population was miserable. Life in its solitary confinement cells (if it could be called living) was even worse.

Egan had got to know life in general population all too well and solitary far better than any convict could ever want to. His nine years there had entailed regular conflict with guards and other convicts punctuated by many stints in solitary. The reforms instituted by Warden James Johnston before he left for San Quentin and later Alcatraz had withered since Johnston’s departure in 1913. Worse still for Egan he served some of his time there under iron-fisted Warden Court Smith who was appointed in 1927. Previously Visalia’s police chief and Tulare County Sheriff, Smith had earned a brutal reputation while Warden at Folsom.

Court Smith later became Warden at San Quentin until being dismissed in 1940. Under Smith San Quentin had received serious, persistent allegations of brutality and corruption extending from the Warden himself right down to ordinary guards. By the time Smith was fired appalling allegations of bribes and brutality forced a wholesale purge of prison administrators. Smith himself was accused of running a secret underground dungeon where prisoner were starved, beaten and tortured, some of them until they died.

When Smith was fired almost the entire Prison Board went with him. When Clinton Duffy was appointed temporary Warden he immediately fired the Captain of the guards, replacing him with a Sergeant whose first job was emptying Smith’s dungeon within one hour. Humane and reform-minded Duffy might have been able to steer Egan away from the gallows, but Duffy wasn’t in charge at Folsom during Egan’s tenure. Until he was replaced at Folsom by J.J. Smith in1932 (ironically appointed by Governor Rolph) Court Smith certainly was. Every Folsom inmate knew that and accepted it however much they might have loathed him. Those who didn’t were made to suffer until they did.

By modern standards conditions at Folsom were brutal in the extreme. In the old cellblock the cells were tiny, measuring only four feet by eight. Built using convict labor and the nearby stone quarry they originally lacked either toilets or running water. Until the 1940’s the cell doors had only a six-inch slot for light or fresh air making them miniature saunas in summer. Even when rows of holes were drilled they still stank. Some are used even today.

In documentary series ‘Notorious Prisons’ former Folsom guard Jack Peart described their foulness. “In the old cellblock there was no ventilation in those old cells. There was buckets in there you had to go in and a bucket to drink out of and it was the stinkingest damned old place in the world. Worse than a stable.”

Violence between convicts and staff alike was endemic. The food was of low quality and limited nutritional value even when there was enough, which wasn’t always. Minimal portions of unhealthy, stale prison slop were the order of the day. Plates were nailed to tables and cleaned by throwing buckets of water over them between mealtimes, a constant risk of disease. By the time Egan arrived things had improved considerably, but the food was still nothing to write home about.

Prisoners were still expected to perform twelve hours hard labor every day regardless. With few safety precautions in Folsom’s stone quarry accidents were common. Prisoners were regularly injured or killed and there was little official interest in their safety. With little official interest even less was done to improve the quarry’s accident record. Occasionally guards were injured or killed as well.

Harshest of all were the punishments for even the slightest infraction. At various times prisoners were ‘triced,’ hung in chains with their feet barely touching the ground and left to suffer. Their bones and joints could easily suffer permanent damage. To make this punishment even harsher many were periodically hosed with ice-cold water. Some were also beaten as they hung like skeletons in some medieval dungeon. Rubber hoses, clubs, blackjacks and brass knuckles were routinely used, dishing out unofficial punishments to beat the disobedient into submission. Some guards avoided inflicting beatings personally, discreetly ordering other convicts to do it.

Worse befell those prisoners guards especially disliked. The sweatboxes, cells even tinier than the standard ones, roasted prisoners in summer and resembled refrigerators in winter. They were so small prisoners were unable to sit or stand, merely suffer. Worst still were prisoners forced into straitjackets and left in solitary for months on end, lying in their own filth and pitch-darkness as Folsom’s solitary cells allowed virtually no light. Straitjacketed prisoners could also be force-fed large amounts of laxatives.

Not until 1913 and Warden James Johnston were the straitjacket and tricing finally outlawed. Many of the old cruelties were gone at least temporarily. Many of the old staff were gone for good. Those unable or unwilling to accept Johnston’s reforms left and others Johnston fired on general principle. With Johnston now long gone Court Smith was prepared to overlook much of the old-style cruelty. Doing so at San Quentin was later his downfall.

Egan had gone to Folsom in 1923 and had become thoroughly embittered during his time there. He later blamed his crime in Los Angeles squarely on Folsom, especially a lengthy stay in solitary. By his own admission Egan left Folsom more maladjusted than when he arrived, nursing a deeply-held grudge against society and with a firm conviction that it owed him something for making him suffer so badly. As Egan himself remarked that he was “Embittered against society… with the intention that society owed me a duty, and I was going to collect that duty.”

Society, of course, thought otherwise. As far as Los Angeles citizens and the law were concerned Egan’s armed robbery and murder meant he owed even more than he’d already paid. Senselessly murdering William Kirkpatrick didn’t inspire mercy from the courts orr Governor Rolfe, either. Just as Egan had decided society had a duty he was determined to collect, they too felt Egan should pay in full. Unusually, Egan himself agreed with them.

Alvarado and Johnson were already dead, killed during the Bank of America robbery on 24 August 1932. That left Egan, Turcott and Rogers to face justice and possibly the hangman’s rope. Egan pleading guilty thoroughly ruined any chance of his two surviving accomplices winning an acquittal. His pre-trial request to plead insanity was denied. Having previously denied having four prior convictions (two in California and two elsewhere) Egan then insisted on admitting them. Initially pleading not guilty, Egan also changed his plea several days into the trial.

Pleading guilty meant only one thing, Egan would be condemned to hang either at San Quentin or his former home at Folsom. Before accepting his plea the judge thoroughly questioned him. Was Egan sure of what he was doing? Was he sure, knowing it meant a death sentence, that he still wanted to do it? Was he fully aware that he was headed for the gallows of his own free will? Had he grasped, completely and fully aware of the consequences, that he was effectively signing his own death warrant?

During the judge’s questioning Egan dug himself even deeper. He openly admitted intending to rob and that he carried a gun intending to use them on anybody he felt obstructed him. Of shooting William Kirkpatrick he remarked callously “I gave the man full warning.” When asked about the storekeeper chasing them in a commandeered car Egan responded “I had an army Springfield… I figured if he had tailed us four more blocks I would have shot him.”

Dallas Egan was fully aware of all those factors and pled guilty anyway. With Egan’s plea entered and accepted the judge had only one duty left to perform and did so promptly. Egan was sentenced to hang and his co-defendants’ trial proceeded without him. Egan’s guilty plea made the verdict almost a formality. Both convicted, Homer Rogers and George Turcott drew life imprisonment. Had the jury not recommended leniency for Rogers both men could easily have joined Egan on the gallows. By the time their sentences were handed down their friend Egan was on his way to Condemned Row.

For Egan that might have been an improvement. Had he drawn life instead of death he would probably have returned to Folsom, a prison so grim convicts nicknamed it ‘the end of the world.’ Already known to the guards as a trouble-maker Egan would likely have been made to suffer even if he had become a model prisoner. Given that Egan blamed his previous stay there for his avowedly anti-social attitude (which may or may not have been true) his becoming a model prisoner was at best unlikely.

Now in the shadow of the gallows it made no difference whether Egan went to Folsom or San Quentin, he wouldn’t stay long in either institution. Both had a gallows and the State of California wasn’t afraid to use them. Neither his crime or his lengthy criminal record would gain him any sympathy from appellate judges or the Governor.

Egan was also forty years old. He knew full well that even at that comparatively-young age a life sentence probably meant exactly that. Even if he was eventually paroled again it would likely be only when he was too old or infirm to enjoy whatever life remained to him. If that was the case then he’d rather get it over with. The end would come quickly in a hangman’s noose, not a dreary, cold, damp cell smaller than a parking space. Folsom might be the end of the world to most convicts, but the end of Egan’s world couldn’t come soon enough.

Given the conditions at Folsom Egan’s decision is less surprising than it seems. His future consisted of dying in prison, either of old age or the hangman’s noose. Boiled down, he could die quickly or slowly and imprisoned either way. A decade later labor racketeer Louis ‘Lepke’ Buchalter made the same choice even when offered leniency for information. On 4 March 1944 Leple went to Sing Sing’s electric chair after deciding the deal wasn’t good enough.

Either Egan didn’t mind dying, actively wanted to or simply feared Folsom. It made no difference. Judge Pacht had given Egan what he wanted albeit much to Pacht’s dislike. A committed abolitionist, Pacht hated passing death sentences as much as executions themselves. For his part Egan had no complaints, but did have one particular desire. When his time came he preferred to die at San Quentin, not Folsom. Even the thought of a few months in Folsom’s cells was intolerable.

The request was duly granted. Egan went to San Quentin’s Condemned Row instead of Folsom’s. When the gas chamber was installed at San Quentin in 1937 the top floor of the prison’s North Block became the sole accommodation for California’s condemned. Folsom’s gallows was closed the same year after its 93rd and last hanging, murderer Charles McGuire on 3 December 1937.

A few inmates were still hanged at San Quentin until California’s last, murderer Raymond Lisemba on 1 May 1942. Their death sentences had remained, but California law made no allowance for those condemned before the gallows was discarded. Had Egan made his request a few years later he would have died at San Quentin anyway.

If anyone expected a cell in ‘Hangman’s Hall to change Egan’s mind they were both surprised and disappointed. Egan was determined to die. Governor Rolph was intrigued by Egan’s attitude and questions were raised about his sanity. Was he fit to execute? Rolph, still unsure, offered a clemency hearing. Egan was having none of it. Nor was he appreciative of his lawyer’s efforts to save his life.

Egan informed Rolph that he wanted no clemency or for Rolph to even consider mercy, remarking “I can think of nothing better than the drop through the gallows. I am a criminal at heart and I want to be hanged.” It may have been that Egan felt guilty over murdering William Kirkpatrick so unnecessarily. If so, why had he done it in the first place?

To his long-suffering lawyer he was even more specific. Egan sent a written request to the State Supreme Court, asking them to confirm his execution without delay. The request made mention of his attorney, requesting “Should Mr. William O’Shaughnessy, my true and faithful attorney, overrule my voice… fine him $1.98 and court costs for having a heart too big for his Irish soul.”

With that resolved all Egan could do was wait. He wouldn’t have to wait for long. Between 3 January 1930 and 8 December 1933 California had performed forty-one hangings averaging over a dozen per year. Egan’s would be 1933’s eighth and another three followed him before the year’s end. If Egan wanted to hang the State of California would oblige.

As time passed Egan was a model prisoner. Some condemned prisoners become increasingly fearful, sometimes going insane as their time approaches. Others see Condemned Row as their last chance to be as troublesome as possible, even plotting or attempting escape. Some have attempted to escape California’s death cells, but none have succeeded. Others grow calmer under pressure. After months or years of seeing others led from their cells never to return their own end somehow becomes easier. Egan was different from most of them. He arrived without any intention of leaving alive.

He didn’t avoid one of California crime’s long-standing traditions, ‘Black Friday.’ Now a familiar phrase to shoppers world-wide, California’s convicts knew it long beforehand as something far darker. At the time San Quentin usually hanged at 10am on the first Friday of the month unless a prisoner received a stay of execution or clemency. Egan was no exception, his date was set for 10am on Friday October 20 1933.

Egan might have been willing to die, but was still nervous. By 1933 many lurid newspaper reports had offered every grotesque detail of botched hangings. Tales of slow strangulation by too short a drop, decapitation by too long a drop, drunk hangmen, jammed trapdoors and broken ropes necessitating second or even third attempts abounded. It was hardly surprising that Egan wanted something to calm his nerves. It was surprising, illegal in fact, that he got it.

The day before his execution Egan asked for a little whiskey. With Prohibition not ending until 5 December 1933 it might have been compassionate to provide some but still illegal. Governor Rolph didn’t care about Prohibition or criticism for allowing it. Rolph, after all, never minded a little controversy or the occasional drink himself.

San Quentin’s resident physician Doctor L.L. Stanley visited Egan the evening before the hanging. Egan had asked for whiskey in generous quantity and got it. He might have been expecting a small measure of cheap rotgut right before mounting the scaffold. He probably hadn’t expected a half-pint of very good Kentucky Bourbon.

It was gratefully received. According to the Madera Tribune Egan sank two double measures almost as soon as he took the bottle. Declining water or mixers, Egan smiled at the doctor and remarked “I like them straight.” He slept soundly until morning.

Egan was happy enough and so was Governor Rolph. Others, especially temperance campaigners, were very unhappy. In the same Madera Tribune article Mrs Anna Marden Deyo, a friend of Rolph’s and involved with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, openly voiced her disapproval stating

“The fact that Governor Rolph is giving whiskey to a condemned man just before execution to give him a false sense of happiness and dull his senses is a good argument against the use of whiskey in this age when faculty should be well balanced and alert.”

To be fair to Rolph and Egan it was at best po-faced and pompous. It also made no difference whatsoever. The deed was already done. Many Californians either agreed with Rolph’s decision or didn’t mind. It was Egan who faced the gallows, after all, not Mrs Deyo. Prohibition was on its last legs and had never been universally popular in California to begin with. It hadn’t been universally enforced, either.

When the time came Egan was in buoyant mood. He stepped jauntily out of his cell with a cigar in his mouth. After spending his final night sipping whiskey, smoking cigars and repeatedly listening to popular tune ‘Ida, Sweet as Apple Cider,’ Egan decided to surprise his guards one last time.

After a decent breakfast when few would have a decent appetite, he did so. Most prisoners don’t arrive at the scaffold performing an Irish jig. Egan had promised the guards he would and duly did. They took it in stride, applying the restraints and leading their doomed dancer to the gallows. Climbing the thirteen steps unaided (and perhaps a little tipsy) Dallas Egan paid his debt. With a silent signal from the Warden three guards each cut a rope, none knowing which rope sprang the trap.

Egan was silent throughout. He dropped without so much as a ‘Goodbye.’

The stories of Dallas Egan and fifteen other California crooks can be found in my book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in Southern California,’ available in bookstores and online.

2 responses to “Dallas Egan, a half-pint of whiskey (to the last drop).”

-

[…] The judge couldn’t find it within him to argue that point. Egan was given a hearty breakfast and allowed to smoke a cigar. Then, he swigged a few shots of whiskey for courage. Prison officials handcuffed him and led him to the gallows. All along the way, he danced with apparent glee. He climbed the steps, was roped into the gallows, and hanged. He never even gave a final statement. Clearly, he was ready to go.[4] […]

-

[…] The judge couldn’t find it within him to argue that point. Egan was given a hearty breakfast and allowed to smoke a cigar. Then, he swigged a few shots of whiskey for courage. Prison officials handcuffed him and led him to the gallows. All along the way, he danced with apparent glee. He climbed the steps, was roped into the gallows, and hanged. He never even gave a final statement. Clearly, he was ready to go.[4] […]

Leave a Reply