Your cart is currently empty!

South Carolina and the electric chair, a brief history.

With a shortage of lethal injection drugs and no lawful way to get them (using so-called ‘compound pharmacists’ is somewhat frowned on by the Food and Drug Administration), South Carolina has resorted to a choice between the firing squad and dusting off its electric chair. Still commonly called Old Sparky, the chair itself is over…

With a shortage of lethal injection drugs and no lawful way to get them (using so-called ‘compound pharmacists’ is somewhat frowned on by the Food and Drug Administration), South Carolina has resorted to a choice between the firing squad and dusting off its electric chair. Still commonly called Old Sparky, the chair itself is over a century old although its components were updated by no less creepy an individual than Holocaust-denier, fraudulent ‘engineer’ and execution ‘expert’ Fred Leuchter, long known as ‘Mr. Death.’

Purchased from the Adams Electric Company of New Jersey in 1912, it was in use mere weeks after its installation. August 6, 1912 was the twenty-second anniversary of the world’s first judicial electrocution, that of William Kemmler at Auburn Prison in 1890. South Carolina’s first was William Reed, an African-American convicted of attempted rape. Reed, who probably had no idea of the anniversary, was also the first of four men to die in the new chair that year. By Christmas of 1912, Alex Weldon and John Cole (for murder) and Edward Alexander (also for attempted rape) had joined him. Some 240 more would follow until the chair was seemingly retired in 2008 after the electrocution of murderer James Earl Reed. Old Sparky’s retirement proved as short-lived as the prisoners who sat in it.

Just as there would be many botched and clumsy electrocutions, even buying and installing the chair proved problematic. By 1912, Adams Electric was in serious financial difficulty, having trouble paying its own suppliers for parts and construction and had been refused credit by at least one of them. Adams had taken over from Edwin Davis, the world’s first State Electrician, in supplying electrocution equipment and South Carolina was one of several states they did business with.

New Jersey, Massachusetts and Virginia had already purchased their chairs from Adams and other states like Maryland, Missouri, Arkansas and Kentucky were then considering the method. Arkansas and Kentucky went elsewhere while Maryland and Missouri eventually adopted lethal gas. North Carolina, meanwhile, had looked at Adams’ proposal and then found a cheaper local competitor.

Adams Electric, meanwhile, was in deepening financial crisis, Adams having to pay suppliers personally for the South Carolina order rather than through company accounts. Soured by his dealings with North Carolina, it was with an unseemly sense of schadenfreude that he wrote of their cut-price deal causing North Carolina seemingly endless problems:

“From newspaper reports I found that they are still trying to get the outfit to work and that one of the criminals has already had five respites and the chair is still inoperative.”

Adams was right and so were the reports. Far from using a separate generator to power their chair, North Carolina had simply connected it to the main prison supply. The prison at Raleigh had an old, outdated electrical system simply not up to the job of suddenly creating and diverting over 2000 volts every time an execution was performed. Fuses blew, cables melted, circuits burned out and botches were both horrific and a regular feature.

Rather than admit their blunder to Adams or anyone else, North Carolina simply replaced its twin electric chairs (themselves built from wood salvaged from the prison gallows years earlier) with a gas chamber. One of the discarded electric chairs occupied the small airtight room, witnesses describing its first use as both botched and ‘savage.’ At one double gassing the delivery system malfunctioned, Warden McLean having to drop the cyanide pellets into the acid by hand before hurriedly sealing the door. Opinion remained strongly and bitterly divided, some saying the chamber was worse than the chair and others the opposite.

Adams Electric wasn’t in trouble because of negative publicity (the chair hadn’t yet reached its peak popularity, by which time over twenty states had one), but through simple cash flow difficulties. Relatively few people at the time opposed capital punishment, let alone thought to pressure companies supplying chemicals or equipment as they do today. Nor did South Carolina have any problems doing business with Adams, given his previous experience. Their acceptance of his terms was simple and forthright:

“We accept your propersition [sic] of April, 22d, 1912, and agree to pay you 40 per cent on the delivery at the S. C. Penitentiary of the Electric Chair and other necessary equipments and 40 per cent when installed and successfully tested and the balance 20 per cent after the first execution.”

That first execution was originally scheduled for June 1, 1912 but, fortunately for Adams, it would be delayed. Getting parts made and even blueprints reprinted proved both time-consuming and difficult. For a company already in financial difficulties getting credit proved even tougher and even when some parts were delivered they arrived broken and had to be replaced. Adams, a man of some foresight, had already factored in extra time for any delays. Even so, his chair was not delivered to the State Penitentiary in Columbus until June 24. It would not be long before it had its first occupant. William Reed was slated to die on August 6 and did so.

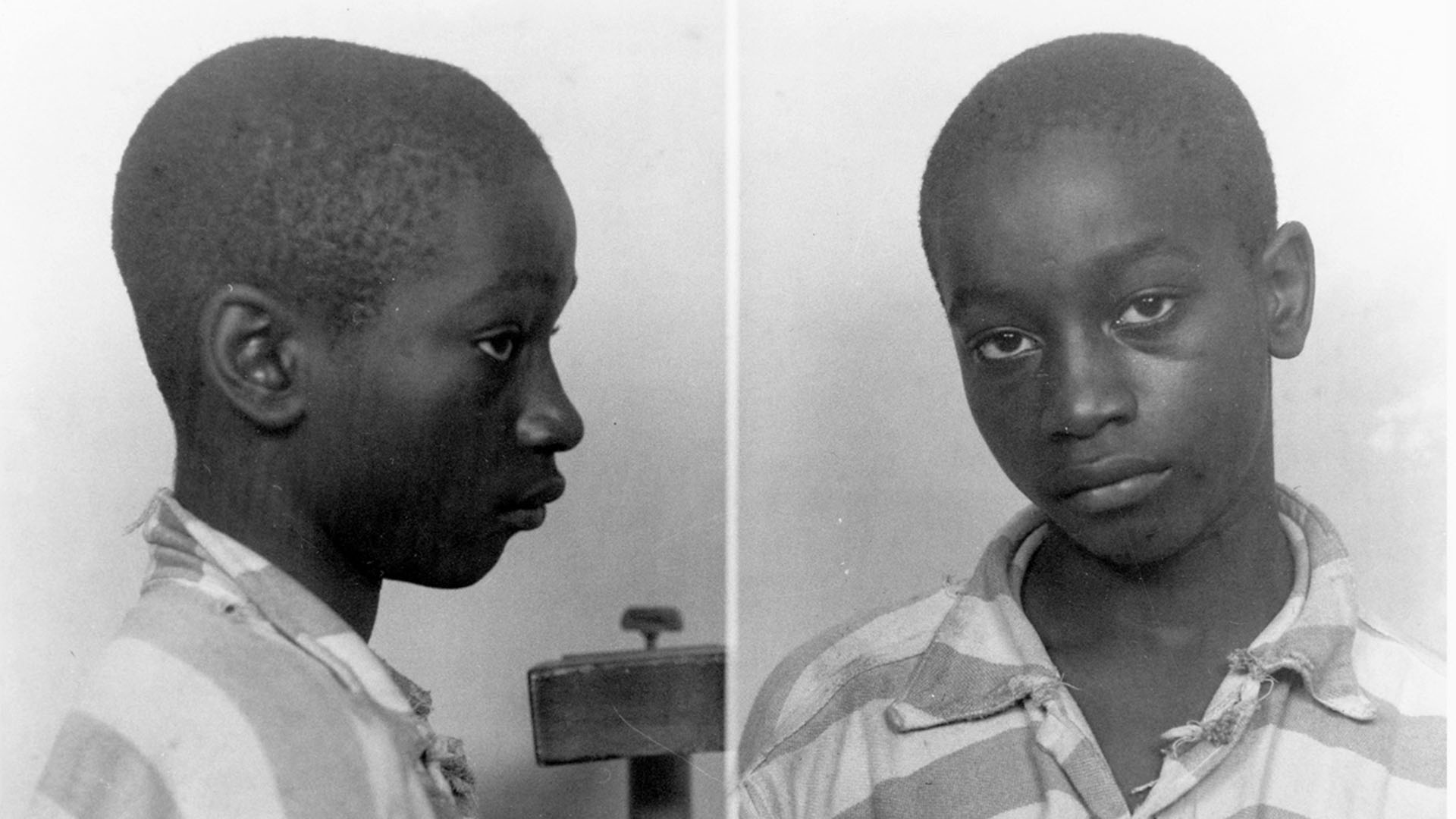

Whether Reed was guilty or innocent we will probably never know. Such charges were common in the South, especially against people of colour, were by no means always solid and were often racially-motivated. The case of George Stinney (pictured above as he entered the death house) stands out, but there were all too many others. What we do know is that, unlike North Carolina’s cut-price version, Adams’ equipment functioned perfectly well. According to the next day’s newspapers nothing went wrong and Old Sparky had become a seemingly-permanent part of South Carolina’s judicial arsenal. Now, long after electrocution has been almost entirely abandoned and largely discredited as a more humane (or less inhumane) method, South Carolina has chosen to dust off its ‘mercy seat’ and start again.

South Carolina no longer issues public information on its electrocution protocol, but it has been suggested its method relies more on a series of high-voltage jolts rather than raising and lowering the voltage and ampage as in many other states. Other accounts from previous executions suggest otherwise, that a variation of the methods perfected by Robert Greene Elliott back in the 1920’s and 1930’s is still in use. The ‘Elliott Method’ or ‘Elliott Technique’ is still in use even for computer-controlled chairs today.

Since their last electrocution was of James Earl Reed in 2008, it remains doubtful whether South Carolina even has any prison staff left who have performed or perhaps even seen an electrocution. After so long a lay-off they might not have more than one or two with any actual experience. Although their staff do train regularly this is not reassuring. As for the state’s proposed alternative, the firing squad, South Carolina has yet to issue or even compile a protocol for its use. Perhaps Utah which already discarded the firing squad some years ago, might be able to assist.

Leave a Reply