Your cart is currently empty!

America’s First Trial by TV: The Bombing of Flight 629

At Denver’s Stapleton Airport, United Airlines Flight 629 bound for Alaska is cleared for take-off at 6:52 p.m. on November 1, 1955, 15 minutes after its scheduled departure time the “Mainliner” makes a perfectly normal take-off and disappears out of sight. Eleven minutes later it explodes near the town of Longmont and wreckage is strewn…

At Denver’s Stapleton Airport, United Airlines Flight 629 bound for Alaska is cleared for take-off at 6:52 p.m. on November 1, 1955, 15 minutes after its scheduled departure time the “Mainliner” makes a perfectly normal take-off and disappears out of sight. Eleven minutes later it explodes near the town of Longmont and wreckage is strewn over several miles. All 44 passengers and crew are killed.

Terrorism? Accident? Mechanical failure?

Once investigators recovered the wreckage their first job was identifying the victims and establishing the cause of the explosion. They found no signs of structural fatigue, faulty parts or botched maintenance. The fuel lines and tanks seemed normal. Nothing suggested any ordinary malfunction. Interviews with ground crew and maintenance crews showed the plane was perfectly sound when it took off.

Investigators then noticed two very disturbing facts. Parts of the fuselage covering Cargo Bay 4 showed scorch marks. A sizeable hole in the airframe had its edges blown outward, suggesting an explosion inside the cargo bay. Investigators noticed a strong chemical smell coming from passengers’ luggage, particularly remnants of an unidentified suitcase. The aircraft wreckage identified as parts of Cargo Bay 4 smelt similar.

Both smelt of explosives.

The FBI examined the wreckage and the suitcase, confirming the suitcase had contained a large amount of dynamite. Parts of the wreckage tested positive for chemicals used in the manufacture of dynamite. They also confirmed that Cargo Bay 4 was loaded at Stapleton Airport. That didn’t confirm a bomb as passengers are sometimes foolish about what they put in their luggage. But It certainly made a bomb the most likely source and Stapleton as where it had been loaded.

In the mid-1950’s, before terrorism became commonplace, airport security was almost non-existent, especially on domestic flights. A bomb could easily be slipped aboard an airliner. Only a few years earlier a Canadian airliner was destroyed by a bomb in a passenger’s luggage. Albert Guay and his two accomplices had wanted to kill his wife. Killing 23 other passengers and crew was collateral damage. All three had been hanged only a couple of years previously.

Their next job was to identify the passenger whose suitcase reeked of explosives. It belonged to Daisie King. King’s personal effects included a newspaper clipping about her son, Jack Gilbert Graham, regarding his latest criminal trial. It wasn’t his first time in court. That instantly made him very interesting. A full background check gave detectives many reasons to look more closely.

Graham wasn’t a son to be proud of. Aged only 22, he’d already collected several convictions in Colorado and Texas and was suspected of many more crimes. Fraud was his specialty, passing forged checks and using other people’s property to secure loans. Petty theft from his workplaces and suspiciously bad luck with expensive items of property also provided ready cash.

Whenever Graham needed extra money he always had some type of ‘accident’ and collected the insurance. In addition to claiming for a pick-up truck destroyed when he stalled the engine on a railroad crossing (in front of an oncoming train) there had been an unexplained gas explosion and fire at his mother’s diner and a break-in. Graham, employed there, claimed insurance for both accidents.

At the time of the bombing Graham was helping his mother run her diner. His earnings were low as he was under a court order to repay money embezzled from a previous employer. In 1951 Graham had been working at a Denver factory. He’d removed 42 checks and forged the owner’s signature, pocketing $4200. His long-suffering mother made a deal with Colorado authorities. In return for no jail time she returned $3,000 dollars of the stolen money.

She also agreed that Graham would work for her, paying the remainder out of his wages. He also drew five years probation. Records showed regular payments. Further checking showed he hadn’t gone straight. Graham used some of the diner’s equipment to secure a loan without informing his mother. Given his repeated crimes, pathological dishonesty and barely-existent work ethic, their relationship grew increasingly bitter. In turn, Graham’s resentment of his mother and what he saw as her constant meddling mutated into hatred.

Graham’s father died in 1937 when he was 3. His mother gave him to an orphanage where he spent the rest of his childhood.. Even though his mother remarried in 1941 she left her son at the orphanage. He didn’t live with her again until 1954 when her new husband died.. Her son bitterly resented that. Placing him in an orphanage and leaving him there longer than absolutely necessary began a bitter rift between them. It didn’t help that she was a bossy, domineering mother, seldom missed an opportunity to further entrench herself in his life.

By the time of the bombing, Graham was living with his wife in a house bought by his mother, on condition that she could stay there whenever she visited Denver. She employed at her diner. She helped him whenever he was in trouble, putting him increasingly in her debt financially and psychologically. To Graham, being beholden to her, subordinate to her and tolerate her increasingly controlling presence became increasingly infuriating. He wanted her out of his life permanently, no matter how he did it.

According to his half-sister, Graham had a violent temper and a perverse sense of humor. Jokes too twisted for most people were his stock in trade. Confrontations he couldn’t worm his way out of were resolved violently. His mother had been terrified by him more than once. His half-sister avoided him on account of his having assaulted her more than once. She told investigators that he assaulted his wife. Graham had married Gloria, 22 at the time of the bombing, only two years earlier. They lived together with their 20 month-old son Allen at the home bought for them by his mother In her opinion he harboured enormously repressed fury mostly focussed on his mother.

Detectives considered him a prime suspect. They invited him to identify his mother’s luggage and answer some routine questions. Smarter criminals know full well that can spell disaster; Detectives don’t usually interview people unless they’re already suspicious. However, Graham felt being obstructive would arouse much more suspicion. He arrived, answered some questions and positively identified the suitcase remnants.

He also mentioned her carrying shotgun cartridges in her suitcase as she’d intended to hunt caribou during her trip. He didn’t realize was that he’d upgraded himself from a prime suspect to the prime suspect. After talking to Graham detectives firmly believed he was their man. Soon after questioning him they had overwhelming proof.

Investigators began sifting through his friends and acquaintances looking for further evidence. They found plenty. Graham’s half-sister filled them in on his darker side. Police files revealed his considerable criminal record. They soon found evidence of bomb-making ability as well.

Investigators went all round the Denver area interviewing people who sold explosives, fuse wire and blasting caps. Strange though it might seem, were available in Colorado at the time over the counter at hardware stores. Soon enough, a store owner in Kremmling positively identified Graham as having bought 25 sticks of dynamite, two blasting caps, batteries and wire.

Another storekeeper remembered him buying an electric timer. Graham was remembered because he returned a few days later, exchanging it for a different type. They also turned up another crucial witness. Graham had briefly taken another part-time job and his choice was hugely significant. He’d work at a store selling and repairing electrical goods. It was a good place to learn how to wire a timing device correctly and investigators had no doubts that Graham did so.

With the new evidence it was easy for police to justify searching his home. Their discoveries ticked all the remaining boxes. Hidden behind a shelf, investigators found a $37,500 insurance policy taken out on Daisie King at Stapleton Airport before her flight. In the 1950’s nervous passengers often bought such policies from vending machines. Provided they remembered to sign them, they were perfectly valid. This particular policy wasn’t signed, making it worthless. There were two other policies as well, bringing the total insurance to $40,000 if Daisie King died. All the policies listed Graham as sole beneficiary.

Detectives also found tools, along with yellow wire and batteries similar to those in the bomb.. One particularly damning discovery was a large box of shotgun cartridges. According to Graham his mother had had put them in her suitcase, thus offering a suspiciously ready-made explanation for what had happened. Unfortunately for him they were found at his home.

His next disaster involved a gift he’d slipped into his mother’s luggage. He’d denied adding anything to her bags before take-off. His wife Gloria also denied him doing so. They were lying. Other witnesses reported Graham as spending considerable time looking for such a gift. Witnesses at the airport reported seeing him put it in her suitcase. Then, despite his previous denials, he conveniently remembered a large toolkit for making jewellery. Daisie King was keen on arts and crafts so it was a fairly obvious choice. Detectives soon identified the kind of kit. It was easily done as that type was seldom sold in Denver.

Other airport witnesses were questioned. They’d seen Graham in the airport café for some time after Flight 629 departed and noticed his extremely nervous state. A United Airlines employee recalled Graham calling them after the explosion, asking if his mother was OK. On hearing his mother was dead Graham’s replied “Well, that’s just the way it goes.”

Detectives obtained a similar toolkit for comparison. The box was big enough to hold 25 sticks of dynamite and a timer. The steel used in that box forensically matched the remaining unidentified fragments in the wreckage.

Investigators now had means, motive, opportunity and a perfect suspect. Witnesses proved Graham bought explosives, bomb parts and a box large enough for the bomb. The electrical repair store’s owner proved Graham had very briefly worked for him. His half-sister revealed his violent temper and his previous criminal record was on file. He and his wife had lied when interviewed and been caught. Airport witnesses confirmed seeing Graham with his mother, that he watched her board the plane and seemed extremely anxious when the plane was delayed 15 minutes. His reaction to the airline employee telling him about his mother’s death was incredibly suspicious and very damaging at his trial.

The reason for his anxiety was simple. He’d set the bomb to explode 25 minutes after take-off. Had it taken off on time the ‘Mainliner’ would have exploded over the Rocky Mountains. In mountainous country recovering even some of the wreckage would have been far more difficult and made Graham’s chance of getting away with it much greater. The delay was only a tiny hitch but, as any experienced detective can tell you- tiny details often ruin the cleverest plots.

Other exhibits were equally damning. Three insurance policies totalling some $40,000, found where they’d obviously been deliberately hidden. FBI analysts confirmed the yellow wire was used in the bomb. Bomb-making tools were found at his home. The deeper investigators dug, the more incriminating evidence they unearthed. Graham’s lie about not slipping a package into his mother’s suitcase was the clincher.

Graham broke and confessed everything. Barring the trial, now a virtual formality, there was nothing between him and the gas chamber. His best prospect was pleading insanity and spending the rest of his life in a psychiatric institution.

Graham was held at Denver County Jail. Strange though it sounds, in 1955 bombing an airliner wasn’t a Federal offence. State prosecutors didn’t need it to be. They had overwhelming evidence for 44 counts of first-degree murder. They only needed one conviction for a death sentence, mandatory for first-degree murder in 1955 under Colorado law. With so many victims, prosecutors obviously chose one most likely to secure a death sentence. Not surprisingly, they prosecuted for Daisie King’s murder.

The trial was a media sensation. It began in January, 1956 and lasted until May. The sheer amount of evidence, witness testimony and complex forensic evidence took months to present. Graham recanted his confession and pled insanity. Given his crime, this was far more credible than in many murder cases. Psychiatrists concluded he was legally sane and fit to stand trial. This might seem strange, but legal insanity and medical insanity are very different.

To be certified medically insane is complex. Legal insanity is simpler, consisting of establishing whether the defendant knew what they were doing and that it was criminal. If their criminal responsibility is established even defendants with multiple mental illnesses can still stand trial. Graham knew exactly what he was doing. He plotted the bombing for the maximum likelihood of evading detection and hampering rescue and recovery operations. He knew full well his bomb would probably kill all the passengers and crew. He simply didn’t care.

Having established Graham’s legal sanity, the court considered whether the massive media coverage was in the best interests of justice and the defendant. The Colorado Supreme Court decided freedom of the press took precedence and the trial judge could decide what coverage was permitted. Judge McDonald gave the media a virtually free rein and Graham’s trial became the first American trial to be televised. Viewers could watch lawyers arguing, watch Graham try to escape justice, see much of the evidence and draw their own conclusions from their own living rooms. This unprecedented move not only catered to the huge media interest, but increased that interest still further.

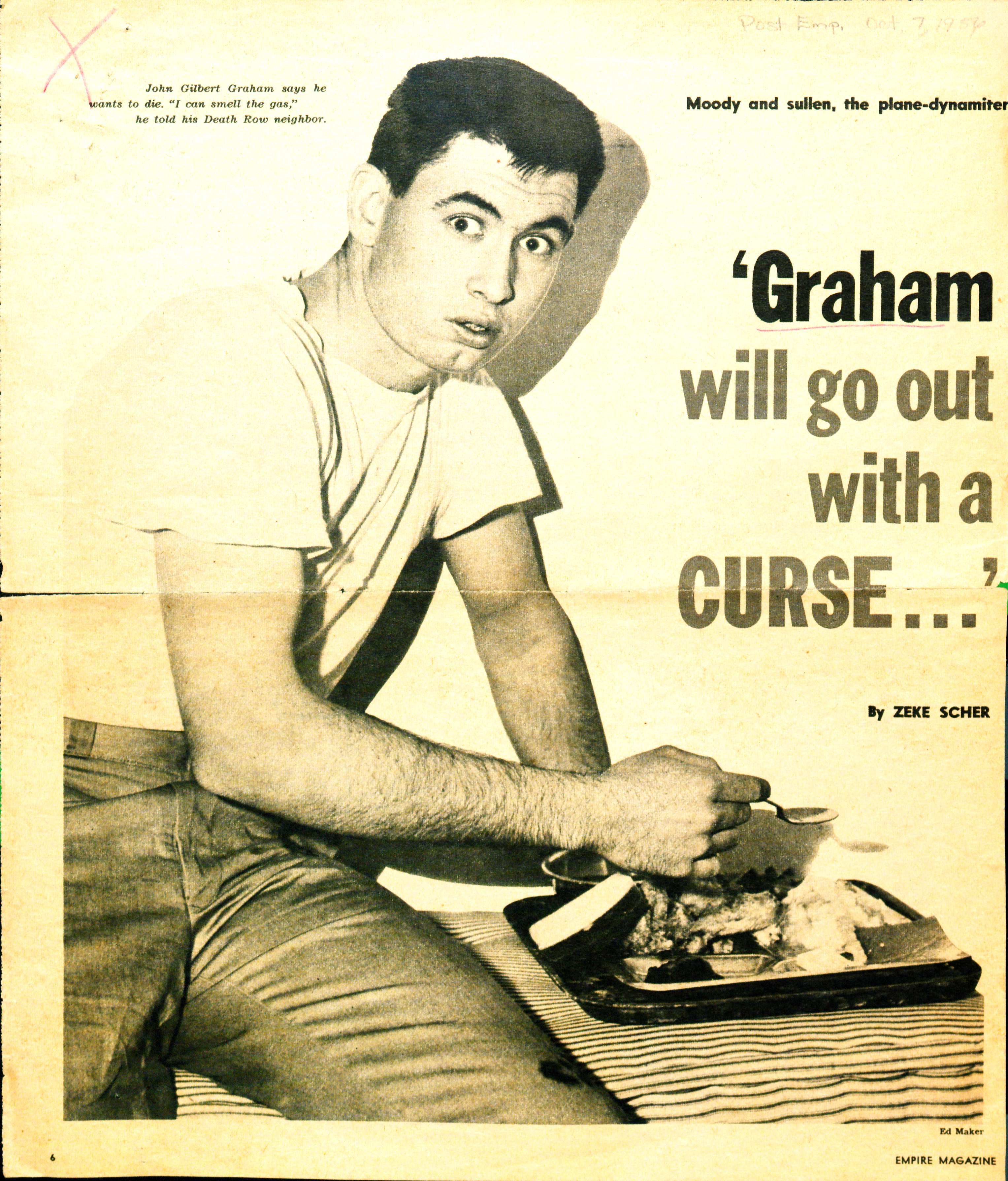

The trial was virtually a foregone conclusion. The question wasn’t whether Graham was guilty or innocent. It was whether he would be ruled insane and sent to a psychiatric institution or ruled sane, meaning either death or life imprisonment. Graham’s attitude was ambivalent. He recanted his earlier, highly-detailed confession, adopting a cold, callous, disinterest throughout.

His demeanor displeased the judge, jury, media and TV audiences. Graham was widely regarded as exactly the kind of defendant the gas chamber was invented for. The prosecution presented an overwhelming case comprising witness testimony, forensic evidence and Graham’s own confession. With so much solid evidence a first-year law student could have won a conviction.

With so little to work with and such overwhelming opposition, Graham’s defense lasted only two hours. His lawyers brought witnesses disputing the testimony of the storekeeper who sold him dynamite, batteries, blasting caps and wire. Graham refused to testify, asking that his wife be barred from testifying too. At the time, wives couldn’t testify against their husbands and his request was granted.

With no alternative arguments, an obstructive client and the overwhelming prosecution case, no meaningful defense was possible. In May, 1956 the jury delivered their verdict after deliberating for only 72 minutes: Guilty. It only remained for Judge McDonald to pass sentence and he wasted no time doing so. The death sentence was promptly passed.

Graham was to be removed from his cell in Denver to the Colorado State Penitentiary at Canon City. There he would be lodged on Death Row under constant observation until execution in the gas chamber. Installed during the tenure of Warden Roy Best, the chamber was known as ‘Roy’s Penthouse’ although it had relatively few guests. Many of those checking in soon checked out into the prison cemetery known as ‘Peckerwood Hill.’

Graham’s indifferent attitude continued. He was outwardly aloof, seemingly no more interested in his own death than the deaths of others. He fought his court-appointed lawyers when they appealed the sentence. His lawyers appealed anyway, without his co-operation and against his wishes. Graham made his feelings clear in a note to appellate judges stating clearly that he wanted to forgo any appeals. Effectively he was volunteering, trying to hasten his execution as much as possible.

In September, 1956 Graham attempted suicide, fashioning a makeshift noose from a pair of socks strengthened with strong cardboard. He almost died, but was discovered and revived before being permanently strapped to a bed with teams of four guards maintaining a 24-hour watch. If he was hoping this would persuade judges to rule him insane he was disappointed. After treatment he was moved back to Death Row.

Neither Graham, the State of Colorado or the victims’ families had to wait much longer. In the 1950’s capital cases usually concluded far more quickly than today. Many were executed within a few months of sentencing. Some died within weeks. Graham was on the fast track to the gas chamber. Warden Harry Tinsley had taken over in 1952 and the reform-minded Tinsley had no relish for supervising executions, even for mass murderers like Graham. The abolitionist Tinsley woulld supervise seven executions between 1952 and 1967, later remarking to the Rocky Mountain News that:

“Execution serves to upset the order and dignty of a prison.”

Graham’s execution on January 11, 1957 was fairly standard as executions go. Graham received a final visit from his wife and took his last meal in his cell. He would be the 26th inmate gassed in Colorado since the chamber replaced the gallows in 1930. His would be the 96th execution since Colorado achieved statehood in 1890.

Not long before the scheduled time, Graham was stripped down to a pair of shorts so wisps of cyanide gas wouldn’t be caught in his clothes, endangering guards who would later remove his body. At 8pm Graham was escorted on the short walk between his cell and the chamber, placed in the steel chair and firmly strapped down.

A custom-made stethoscope was attached to his bare chest, connected via an airtight tube running outside the chamber. A black sleeping mask went over his eyes. Guards exited the chamber and sealed the airtight steel door. At a signal the lever was pulled, dropping several eggs of cyanide into a vat of acid beneath the chair. As the gas swirled up around him Graham’s previously-icy resolve finally crumbled. He started screaming and struggling against the restraints. Less than 10 minutes later he was pronounced dead.

Jack Graham, his mother and 43 other people died because of his obsessive desire for revenge and an insurance policy that was worthless even before the bomb exploded. Graham’s last words summed up his attitude:

“As far as feeling remorse for these people, I don’t. I can’t help it. Everybody pays their way and takes their chances. That’s just the way it goes.”

Leave a Reply