Your cart is currently empty!

On This Day in 1960 – Caryl Chessman, the ‘Red Light Bandit,’ enters San Quentin’s ‘smokehouse.’

Seldom has a condemned convict made the cover of Time magazine, an honour usually reserved for more famous and less notorious individuals, but Caryl Whittier Chessman was no ordinary convict. Whether he really was California’s notorious ‘Red Light Bandit’ is still debated today, decades after he entered the gas chamber at San Quentin. What could…

Seldom has a condemned convict made the cover of Time magazine, an honour usually reserved for more famous and less notorious individuals, but Caryl Whittier Chessman was no ordinary convict. Whether he really was California’s notorious ‘Red Light Bandit’ is still debated today, decades after he entered the gas chamber at San Quentin. What could never be disputed is that he was no run-of-the-mill felon.

Condemned to die in July 1948, Chessman’s intellect and surprising legal ability saw him delay his execution nine times. He fought relentlessly to prevent his execution and prove, so he claimed, his innocence. To do so he learned law as he went, studying how to write and file legal briefs and appeals that frustrated the State of California for twelve years. Finally, on May 2, 1960, his time ran out. By then the former juvenile delinquent, prison escaper and armed robber had become a skilled jailhouse lawyer, best-selling author of both fiction and non-fiction. international celebrity criminal and probably the most famous figure campaigning against capital punishment. His guilt may be debatable, but his metamorphosis is not.

Chessman had been condemned not for murder but under a California law regarding ‘kidnapping with bodily injury for the purpose of robbery. Convicted on seventeen counts, Chessman faced the gas chamber for two of them. It’s often said that the lawyer who defends himself has a fool for a client. For all his undoubted intellect defending himself was probably the worst decision Chessman ever made. In 1948 he knew little about law except having broken it since his teens. What he learned about crime and punishment cam from having spent most of his adult life in and out of Californian prisons.

His arrogant, cocksure manner and sarcastic wit did nothing to inspire either faith or sympathy from the jury in 1948. Nor did his choosing to defend himself on capital charges at a time when the gas chamber was in its glory days. California in the 1940’s and 1950’s was among the leaders in American execution, featuring among the top three or four States for its annual execution lists.

As if that wasn’t dangerous enough Chessman, a career felon with a record as long as your arm, was facing the State of California’s death penalty Dream Team. Prosecutor J. Miller Leavy would secure thirteen death sentences during his lengthy career. Presiding Judge Thomas Fricke still holds the record for the most death sentences handed down by a single judge in Californian history. Chessman really did have a fool for a client.

That fool quickly found himself headed for cell 2455 at San Quentin with two death sentences. Also the title of his first book, Cell 2455 Death Row was cramped and stuffy in the summer. It looked like Chessman would spend the rest of his life in a cell only five 1/2 feet wide, ten 1/2 feet long and 7 1/2 feet tall. Until of course he rode Condemned Row’s infamous elevator down to the ground floor where a smaller and airtight steel box awaited him.

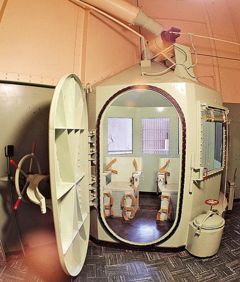

Built in 1937 and first used in 1938, San Quentin’s two-seat gas chamber had long been known by several other names. Painted apple-green, some convicts called it the ‘little green room.’ Others gave it names reflecting their grim sense of humour. It was the ‘coughing box, the ‘smokehouse,’ the ‘time machine’ and, most familiar to movie buffs and book-hounds, The Big Sleep.’

Raymond Chandler borrowed the nickname for his 1939 novel and later the Hollywood version released in 1946. Chandler also incorporated lethal gas into one of his mysteries ‘Nevada Gas,’ featuring private eye Philip Marlowe. The world’s first legal execution by gas had been performed in Nevada, that of murderer Gee Jon in 1924. By 1948 California’s chamber had been in service for a decade and was already doing brisk business. Between 1938 and Chessman’s death in 1960 Chessman saw over 100 men walk their last mile past his cell never to return. All things considered it looked as though Chessman would sit quietly and die within months of arriving, but that was not to be.

Chessman was unusually intelligent with an IQ of 128. Not a genius, but certainly well above average. He quickly grasped that without money and expensive lawyers he would have to fight his case himself. For a remarkable twelve years (when most condemned prisoners barely lasted as many months if they were lucky) he did so. He learned fast and well, defying prison orders and snap searches to help other prisoners with their own cases. He also wrote fiction only to have problems getting manuscripts of any kind except legal in and out of the prison. Rather than sit quietly or cause the usual convict trouble of escapes, riots and violence, Chessman learned to use his mind rather than his trigger finger. As a result he gave the authorities more trouble than by brawling and general trouble-making.

Chessman did have some solid grounds for appeal. The court reporter at his trial had been a chronic alcohlic who shorthand notes were both incomplete and often barely legible. Chessman filed a suit complaining that the record, which had been ‘completed’ by removing over 2000 errors, had been compiled by prosecutor Leavy and one of Leavy’s relatives. He attacked Judge Fricke’s handling of the case, claiming that Fricke had been biased and unfair. He claimed police had beaten his original confession out of him and that eyewitness accounts were inaccurate and mistaken.

It was to no avail. The more publicity Chessman attracted, the more trouble he caused the State. The greater the irritant and embarrassment he became the more the State of California wanted to make an example of him. His non-fiction works Cell 2455 Death Row, Trial by Ordeal and The Face of Justice were best-sellers, Chessman himself regularly gave interviews and became an international figure in the process. One of his last-minute stays of execution came not for any legal reason, but because his date coincided with then-President Eisenhower visiting Uruguay. Fearing unrest in Uruguay during the Presidential visit the authorities in California stayed the execution shortly before Chessman was due to die. Chessman’s international fame had delayed his death yet again.

During his twelve years on Condemned Row Chessman attracted international support and a significant body of opinion doubted either his guilt or whether he really deserved to die. Attorney Rosalie Asher among others worked tirelessly and for free helping him delay his execution. International figures like former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Norman Mailer, Aldous Huxley, Ray Bradbury and evangelist Billy Graham appealed for clemency and Chessman’s plight attracted far more attention than his original crimes. Which raised the question not of whether he should live, but was he actually guilty to begin with?

San Quentin Warden Clinton Duffy, in charge when Chessman arrived on Condemned Row, had no doubts. He knew Chessman well, disliked him intensely and believed he was guilty. Chessman himself denied his guilt, even claiming at one point that he knew the identity of the Red Light Bandit, but wouldn’t inform to protect his parents who the real culprit’s friends had threatened with death. Judge Fricke and prosecutor Leavy likewise had no doubts. To them Chessman was an especially nasty felon whose case should have been quickly resolved with a visit tot he gas chamber. According to Chessman one of his guards personally told him the only cure for him was a pound of cyanide.

Whether he was guilty or innocent, Chessman’s time ran out on May 2, 1960. The previous day he was taken on his latest (and last) elevator ride from Condemned Row to the two barred cells only twelve steps from the chamber itself. The ‘Ready Room’ was a familiar sight by then and Warden Dickson would supervise the execution slated for 10am the next morning. Just the other side of a steel wall the executioners prepared the chamber. Barring any last-minute stays or reprieves, neither of which looked very likely, Chessman would enter the chamber at 10am and be dead by around 10:15. As it turned out the last-minute delay would arrive just that little bit too late. Chessman would die for his crimes, granted, but also by mistake.

Chessman spent his final hours in the Ready Room writing letters and hoping his lawyers could work a legal miracle. They did, but minutes too late. Dressed in the standard shirt and denims with no socks, he entered the chamber knowing a last-minute appeal had been denied less than an hour before the scheduled time. He complained that the short time left no further chance for his lawyers, but was wrong. As it turned out he died anyway.

His lawyers had managed a legal miracle, but the phone call from Federal Judge Louis Goodman rang the phone in the death chamber a couple of minutes after the cyanide pellets and acid had mixed. This, some said, was down to his secretary accidentally dialling the wrong number. By the time she had got through to San Quentin and the open phone line in the death chamber itself, it was just that little bit too late. The executioner, probably Max Brice or Joe Ferretti, had already been signalled to pull the lever dropping cyanide into a vat of acid directly underneath Chessman’s chair, a chair he was securely strapped into. Gas was already filling the chamber even while Goodman was ordering Warden Dickson to delay the execution. A powerless Dickson could do nothing to stop it.

Chessman was already suffering the effects of cyanide poisoning when he gave a pre-arranged signal to witness and reporter Will Stevens. They had agreed before the execution that, if Chessman found the effects of the gas intolerable, he would signal Stevens who would report it later. Chessman did give that signal and, just when things couldn’t have seemed any worse, the phone rang.

Dickson was heavily criticised afterward. He was blamed for not ordering the executioners to turn on the chamber’s extractor fans. Some said that, with the fans turned on, guards could have entered the chamber, released Chessman form the restraining straps and led him out. This was, at best, highly unlikely.

The fans were not designed to draw off gas while it was still forming, but to remove lingering gas hours after an execution was over. Hours after one or two prisoners had been executed prison guards would unseal the airtight door and wash every inch of the interior, including the prisoner(s), with ammonia to neutralise the cyanide. The deceased’s clothes would be cut off and burned before they were sent for burial or cremation.

This, the final part of what became known as ‘Procedure 769,’ was only a two-man job.There were only two sets of rubber gloves and two gas masks to protect around a dozen people including the Warden, Associate Warden, prison Doctor, two Chaplains and eight or nine guards. Even if the guards had managed to free Chessman, risking a dozen or so lives in doing so, he had probably taken enough cyanide to kill him anyway. Dickson was damned if he did, damned if he didn’t.

Even if Chessman had been saved, highly unlikely and by risking a dozen lives on the mere chance of saving one, Goodman’s order was for a temporary delay, not a commutation, reprieve or anything else that would have barred his jailers from trying to execute him again. There would have been nothing at that point preventing them from nursing him carefully back to health only to gas him again weeks or months later. Even if his death sentences had been commuted or overturned, Chessman would still have faced centuries of unserved prison time. The Caryl Chessman story was over.

One response to “On This Day in 1960 – Caryl Chessman, the ‘Red Light Bandit,’ enters San Quentin’s ‘smokehouse.’”

-

[…] working for free, and public support had kept him alive through twelve years and nine appeals. By May 2, 1960, his time and appeals had run out. Neither state nor federal courts saw any merit in his writs, and even death penalty […]

Leave a Reply