Your cart is currently empty!

On This Day in 1916 – Charles Sprague, last man to die at Auburn Prison.

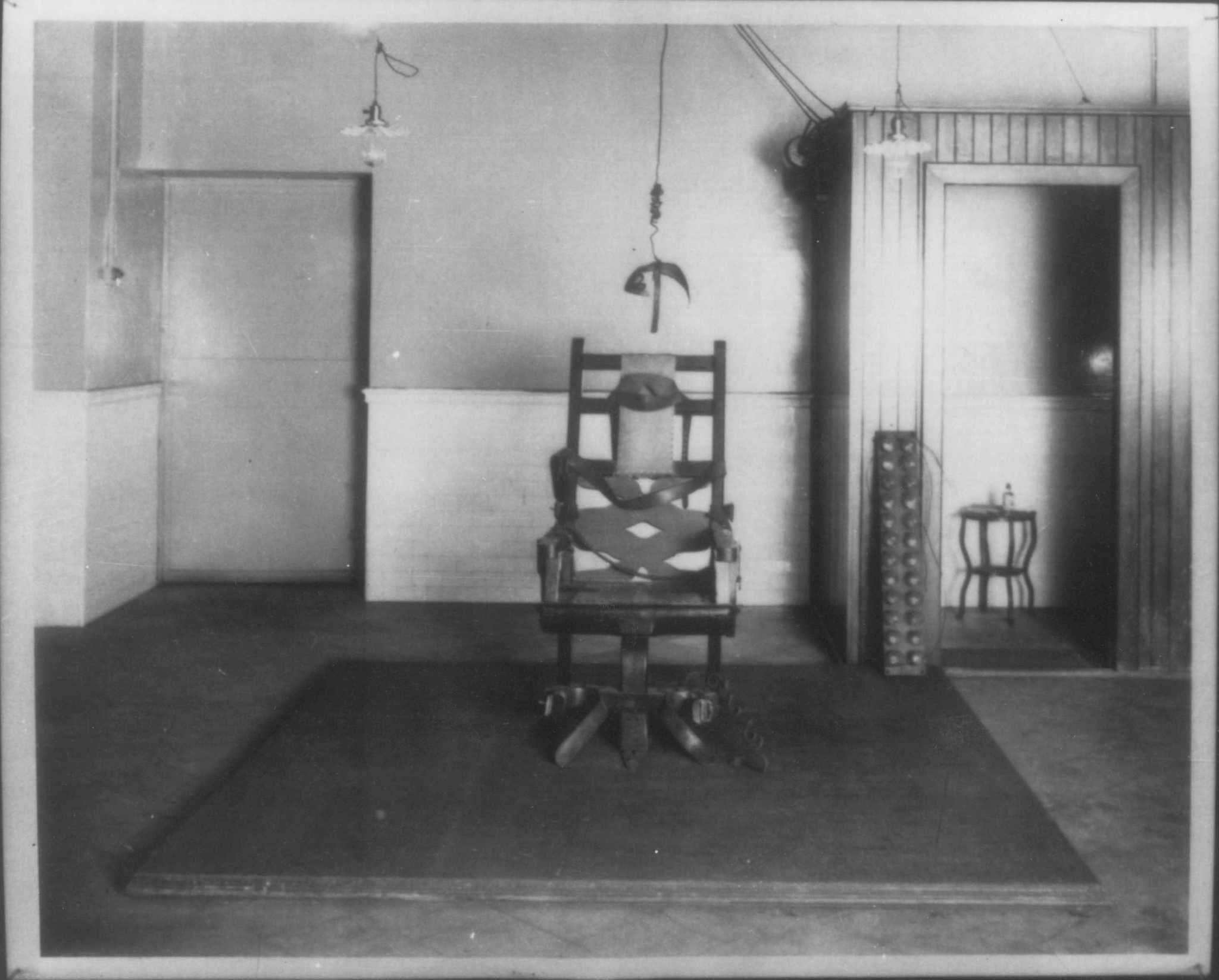

On August 6, 1890 Auburn Prison in upstate New York made history. William Kemmler, drunkard, vegetable-seller and killer, became the first prisoner to die in the electric chair. Bungled though it was (George Westinghouse remarked it could have been done better with an axe, Kemmler’s chosen weapon) the era of ‘electrical execution’ had begun. Despite…

On August 6, 1890 Auburn Prison in upstate New York made history. William Kemmler, drunkard, vegetable-seller and killer, became the first prisoner to die in the electric chair. Bungled though it was (George Westinghouse remarked it could have been done better with an axe, Kemmler’s chosen weapon) the era of ‘electrical execution’ had begun. Despite the Kemmler disaster New York and over twenty other States adopted still adopted ‘electrocution’ as the latest method of ‘humane’ capital punishment.

The era ended at Auburn with murderer Charles Sprague on May 1, 1916. Auburn’s chair (also the world’s first) had killed fifty-three convicts and Sprague would be its fifty-fifth and last. Now sited in its own death chamber with seven death cells nearby, the original Old Sparky was about to be retired. It had seen the world’s first ‘State Electrician’ Edwin Davis earn thousands of dollars learning and refining his profession and the unofficial debut of Davis’s successor John Hurlburt.

Hurlburt, who took over from Davis in 1914, had executed Guiseppe DeGoia and George Coyer under Davis’s supervision on August 31, 1914, would execute 140 convicts between 1914 and 1926. After a dozen years and so many executions a depressed, dispirited Hurlburt resigned in 1926 and took his own life a couple of years later. While Auburn’s chair had seen the debuts of Kemmler, Davis and Hurlburt, it lacked the grim distinction of claiming a female occupant. That had been Martha Place, executed by Davis at Sing Sing on March 20, 1899. On May 1, 1916, though, Charles Sprague was literally in the hot seat.

Sprague was a murderer of no particular note except to his victim, the courts and for being Auburn’s last ‘thunderbolt’ jockey. Out of New York State’s three electric chairs the one at Dannemora had already been retired and in 1915 it was decided that all Empire State electrocutions would be conducted at Sing Sing. Once Sprague was gone Auburn’s death house would be empty and its lights turned out forever. Sprague was about to suffer the same fate en route to becoming a footnote in penal history.

Like so many of his peers Sprague’s crime had been a senseless one that he resolutely blamed on drink. A dispute with George Martin over a potato crop had seen Sprague shoot Martin dead near Jerusalem in Yates County on October 17, 1911. Since then Sprague had sat in one of Auburn’s seven death cells while the clock ran down. According to Sprague the gun had fired accidentally and an inscription in prison Chaplain Copeland’s Bible read:

“I have to leave this world, but I wish I could go knowing that not another drop of liquor would be sold.”

If he was expecting either national sobriety or a last-minute reprieve Sprague was to be disappointed on both counts. Just as Americans, most of them anyway, had no interest in lifelong abstinence the courts and Governor had no interest in sparing his life. As far as they were concerned the matter was closed. So too would be the door to Auburn’s death chamber. Sprague would be Auburn’s fifty-fifth execution and just another date in Hurlburt’s diary. For Warden Charles Rattigan it would be his ninth since taking over at Auburn in 1913.

It was widely-known that it would be Auburn’s last execution. A small note in the Elmira Star-Gazette had appeared a month beforehand reading:

“Superintendent Radigan (sic) of Auburn Prison is being swamped with requests for passes to attend the electrocution of Charles Sprague the 2nd, of Yates County, who is to be executed the week of May 1. He will be the last person to pay the extreme penalty in Auburn Prison. Sheriff Milan Ayres and District Attorney Wood will each get a pass to the execution.”

The issuing of official invites was nothing unusual. As grim as it sounds prison staff need to know that only approved visitors attend executions and this was standard practice at the time. With Auburn in a relatively isolated part of New York State and travel being rather more difficult in 1916 than today, anyone in the area wanting to see an electrocution didn’t want to have to go to Sing Sing to do it. Sprague, of course, had no choice and it made no difference. Whether he sat in Auburn’s chair or Sing Sing’s he would be equally dead either way.

When the time came Sprague, futile though it was, protested his innocence for the last time. With that done sat down, the electrodes and restraints were applied and Warden Rattigan gave Hurlburt the signal. Sprague probably died from the first jolt, but a second was standard practice. With hat done Charles Sprague, Jr was dead and Auburn’s electrocution era, which had included such notorious felons as Mary Farmer, Chester Gillette and Leon Czolgosz, had ended.

Empire State electrocutions, however, had not. Between William Kemmler and Eddie Lee Mays on August 15, 1963 695 convicts were electrocuted in New York and by 2020 several thousand had died elsewhere by the same means. For years the chair had declined and by 2020 it was virtually unused, but could be about to begin a revival. South Carolina, unable to obtain the drugs required for lethal injection, is currently debating whether to restore and reinstate the method it hasn’t used since James Earl Reed in 2008. Whether other States with a similar drug shortage will follow suit is unknown.

2 responses to “On This Day in 1916 – Charles Sprague, last man to die at Auburn Prison.”

-

Charles Sprague was my grandfather my name is Harold Sprague my dad’s name was Howard Sprague come out of bluff point Yates county

-

It must have been a hard thing to live with, especially with all the press attention at the time.

-

Leave a Reply