Your cart is currently empty!

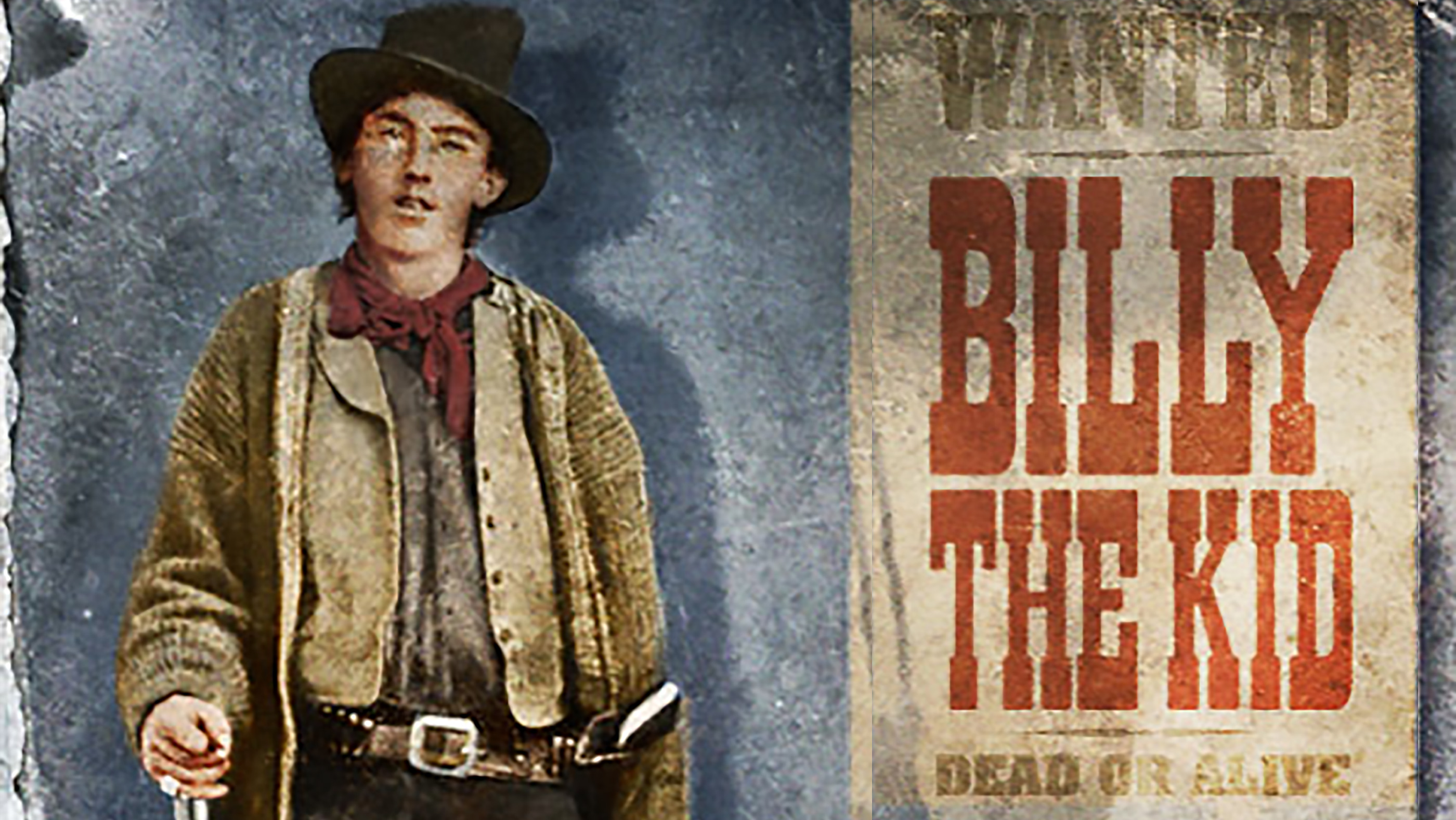

On This Day in 1881, Billy the Kid cheats the hangman.

John Wesley Hardin. Jesse James. Cole Younger. “Curly” Bill Brocius. Gunslingers, killers, thieves and icons of the Wild West. Of all the Western outlaws none has quite the notoriety of “Billy the Kid.” Questionably accused of killing 21 men (one for each year of his short and violent life), Billy is as much a Wild…

John Wesley Hardin. Jesse James. Cole Younger. “Curly” Bill Brocius. Gunslingers, killers, thieves and icons of the Wild West. Of all the Western outlaws none has quite the notoriety of “Billy the Kid.” Questionably accused of killing 21 men (one for each year of his short and violent life), Billy is as much a Wild West icon as Wyatt Earp or ‘Wild Bill”’ Hickok. Ask people today to name the first outlaw that springs to mind and it would probably be Billy. Well over a century after his controversial shooting by buffalo hunter-turned-lawman Pat Garrett and, in spite of being a New Yorker, he’s still marketed to tourists as New Mexico’s most infamous son.

Like so many Old West outlaws, Billy’s public image is a constant blurring between fact and fiction. The man and myth so intertwined as to be almost indistinguishable. His exact date of birth in unknown, his biological father is unconfirmed, he has no accurate body count and stripping fact from fiction is difficult to say the least. We don’t even know for certain what name he even born with.

The most likely start to Billy’s story begins with being born in New York as Henry McCarty in 1859, only a couple of years before the the Civil War that transformed every aspect of American history. Catherine McCarty emigrated from Ireland after the Great Famine of the 1840’s in search of a better life. She did her best to provide for her children, taking them West rather than see them grow up in the New York slums. She was known as a jolly, cheerful lady and Billy’s only positive parental role model.

Billy’s father had vanished. New stepfather William Antrim was far more interested in gambling, gold prospecting and fortune-hunting than in responsible parenting. Antrim often spent long periods away from home and doing little to provide a good example even when he was actually there. Billy’s mother was cut from better cloth. She baked pies, washed laundry, took paying lodgers and whatever else was necessary to provide for herself and her children. She was also dying from the final stages of tuberculosis even when she brought her family West.

Mere months after their arrival in the rough New Mexico town of Silver City she died, leaving Billy alone in the world at the tender age of fourteen. Losing his single positive adult role model, being young and impressionable, the ever-present vices of Silver City and sheer necessity meant it wasn’t long before Billy turned to petty crime to survive.

His first recorded arrest hardly indicated his later infamy. Stealing several pounds of cheese was hardly the work of a master criminal. Even the county sheriff who arrested him found him a likeable young lad whose crime was stemmed from need rather than profit. His sympathy, however, was both short-lived and misplaced. Billy soon graduated to more serious crimes like handling stolen property and more serious thefts, soon becoming a regular feature at the town jail.

Billy was also sometimes reckless and impulsive. He didn’t like jail even for short periods and that caused his first big step into the higher leagues of crime. He escaped from the local jail rather than do the smart thing, finish his brief sentence and go straight. Without parents every young man needs a mentor. Unfortunately, Billy had a close encounter of the criminal kind.

“Sombrero Jack” (whose real name has long since been lost) was a typical low-level burglar, cattle rustler and horse thief, nothing important in and of himself. But he was Billy’s first criminal mentor. He used Billy as a lookout during burglaries, stored stolen property in Billy’s rented boarding house room (protecting himself and having Billy risk a surprise search). Through Sombrero Jack, Billy began meeting and learning from more serious criminals. They tutored him in cattle rustling, robbery, theft, gambling (Billy often wore a gambler’s pinkie ring, used for secretly marking cards) and generally schooled him to become a full-time outlaw.

At Silver City, Billy would also make an acquaintance who finally took him from part-time petty crook to full-time, professional criminal and well past the point of no return. Frank ‘Windy’ Cahill was a nasty piece of work. Boorish, crude, vicious, habitually provocative and one of Silver City’s local bullies, Cahill was always spoiling for a fight. He was especially nasty when drunk, which was quite a lot of the time.

Billy was young, physically small and no match for Cahill in a fistfight. Cahill, like all bullies a coward at heart, particularly singled him out for physical and verbal abuse, assaulting Billy at least a couple of times already when he hadn’t knuckle under as quickly as Cahill wanted. This was Cahill’s (and, with hindsight, Billy’s) undoing.

Cahill spotted Billy one day and, with his customary aggressive and abusive style, began trying to humiliate and intimidate him. This time Billy stood his ground. Cahill became increasingly aggressive and verbal sparring quickly became a bare-knuckle brawl. Cahill was winning and Billy taking yet another beating, but only until he managed to draw his brand-new Colt “Thunderer, a .41- revolver popular with outlaws of the time.” Cahill did his best to force the weapon away from his body but it was too late. Billy shot him in the stomach at point-blank range and Cahill died the next day. By then Billy was in the town jail awaiting trial for capital murder.

The New Mexico Territory wasn’t the safest place to be an outlaw, especially not one facing a possible death sentence. As in many frontier areas the social climate was “rough and ready” and law enforcement (such as it was) reflected that. An outlaw could go to trial and be convicted or acquitted like any defendant, granted, but it could take weeks for circuit judges to be available, travelling as they did from town to town and presiding over whatever cases awaited them. Defendants could just as easily find themselves hanging from the nearest tree, the local townsfolk having opted to skip the legal niceties. Lynch law wasn’t standard practice in New Mexico, but it was no novelty either.

It could be argued that New Mexico’s outlaws feared vigilante justice rather more than the official variety, especially after the Lincoln County War in which Billy was a prime mover. He knew he was in serious danger even though he could have pled self-defense. He solved that problem by escaping the town jail and going on the run. Billy had moved up in the underworld. He’d gone from petty thief and gambler to wanted killer with a price on his head. There would be, and could be, no turning back.

Billy roamed the New Mexico Territory for a while, skipping towns whenever he felt it was time to move on. He supported himself through gambling (especially three-card Monte), small-time theft and cattle rustling. After a few months he found himself in the cattle town of Lincoln. Lincoln was where his legend really began.

Billy arrived in town just as tensions between local cattle barons were beginning to boil up. There were two factions in what became known as the Lincoln County War. One was led by a young Englishman, John Tunstall, and the other by two Irish cattlemen, L.G. Murphy and James “Jimmy” Dolan. The Murphy/Dolan faction was known locally as “The House” owing to Murphy’s grandiose home. The House had a virtual monopoly in Lincoln County. It had lucrative beef contracts with the U.S. Government, supplying meat (usually barely edible and at inflated prices) to Native American reservations and local army units. It also ran Lincoln’s bank and the only store in Lincoln providing other local businesses with essential supplies. It became impossible not to do business with The House and entirely on House terms.

Among their many assets The House also owned Lincoln’s lawman, Sheriff William Brady. In addition to having a stranglehold over local businesses and law enforcement (Brady seldom enforced any law without Murphy and Dolan’s approval), The House extended its corruption into New Mexico politics and an overly friendly relationship with local military commanders. The House started ruthlessly squeezing out smaller ranchers and homesteaders using its political ties and financial manipulation.

Smaller ranchers had to deal with Murphy and Dolan as there was nobody else. Once indebted to The House, bad debts became a pretext for seizing cattle and land to increase the Murphy/Dolan empire. The Santa Fe Ring included top-level political figures and a powerful block of Irish politicians, guaranteeing no hostile political attention or legislative action to curtail Murphy and Dolan’s perpetual empire-building.

Enter John Tunstall. Tunstall emigrated from England, arriving in Lincoln late in 1876. He swiftly began infuriating The House. Working with lawyer Alexander McSween and legendary cattle baron John Chisum (no friend of The House) Tunstall set up a rival ranch, store and town bank to break the Dolan-Murphy monopoly. Murphy and Dolan bitterly resented his doing so. That Murphy, Dolan and many of their henchmen were Irish immigrants and Tunstall was English would only inflame the situation.

Chisum’s backing of Tunstall is unlikely to have been through altruism so much as Chisum wanting to extend his own commercial power and limit that of The House. Chisum provided the money, McSween the legal wisdom, and Tunstall the ambition. That ambition soon cost the lives of Tunstall and many others. Tunstall first encountered Billy in the town of Lincoln and, liking the young drifter, offered him work as a cowhand and, if needed, gunfighter. Billy, seeing an opportunity for a home, job, wage and a chance to settle down and live at least semi-legitimately, accepted.

Tensions between Tunstall and The House rose rapidly. In the absence of a full-time police force, both sides hired groups of gunmen to protect their own interests and threaten each other’s. Hiring freelance gunslingers was standard practice for ranchers and other big business owners at that time. Sheriffs and marshals were few in number and often of limited competence, doubtful sobriety, violent temperament and easily bought.

Many Western lawmen (including many famous ones) didn’t mind running dubious private enterprises to supplement their very limited income from policing (for instance, the Earp brothers indulged in gambling and, some say, pimping as well as law enforcement). Also, the U.S Constitution made deploying troops within American borders particularly difficult and usually a last resort. With very limited legal oversight and an almost complete lack of practical alternatives, employing professional gunmen became the most (if not the only) workable option.

Until Tunstall’s arrival, Chisum had stood alone against The House. Murphy was now dying of cancer and Dolan (his adopted son) took command assisted by another Irishman, John Riley. With the arrival of competition the previously captive customers of The House (many of whom bitterly resented being milked like cash cows) began switching their business to Tunstall and McSween. Dolan’s anger at seeing his ambitions curbed and profits cut (by an Englishman of all people) grew increasingly strong and tensions continued rising. With both sides gathering increasingly large private armies it was only a matter of time before the personal and professional struggle became a shooting war, a fight to the finish based as much on personal prejudice as power and money.

Dolan’s continual harassment of Tunstall was, at first, through “legal” means. Dolan initiated continual legal actions against Tunstall but the Englishman still refused to be run out of Lincoln County. Finally Dolan secured (by corrupt means) a writ of attachment confiscating Tunstall’s money, property and assets, essentially rendering him financially and materially destitute.

Dolan’s tame Sheriff, William Brady, sent a posse to enforce the writ and, knowing full well that some posse members were known outlaws and held personal grudges against him, visited the Tunstall property anyway. On February 18, 1878, one of the posse killed John Tunstall while other posse members shot Tunstall’s horse and laid it down beside its fallen master. It was a brutal and senseless killing, either satisfying the shooter’s personal grudge or on Dolan’s orders. The Lincoln County War had properly begun.

McSween managed to arrange arrest warrants for the killers. Brady refused to recognize the warrants as lawful, refused to enforce them and also arrested the young men deputized to serve them. One of those young men called himself William Bonney, known then simply as “The Kid.” Those supporting Tunstall and McSween realized that the law was already useless and formed a vigilante group to administer their own brand of justice. They called themselves The Regulators and Billy was a founder member.

Revenge was swift in coming. Only two weeks after Tunstall’s murder two of the posse members were shot dead along with a bystander who had tried to intervene. On April 1, 1878 Sheriff Brady and Deputy George Hindman, were shot dead in Lincoln. Only days after Brady’s murder, Regulators killed “Buckshot” Roberts. A notorious gunfighter with a penchant for shotguns, he didn’t die without a fight. Before dying Roberts killed the Regulators leader Dick Brewer and wounded several Regulators.

Lincoln County was now a virtual warzone. Heavily-armed groups from both factions roamed the area skirmishing and killing on a regular basis. The first phase of the Lincoln County War ended in Lincoln itself when the Regulators were cornered at McSween’s home. The siege lasted five days before what became known as ‘the big killing.’. Troops arrived from nearby Fort Stanton ostensibly to protect bystanders and restore order.

However their commander, Lieutenant Colonel Dudley, was a firm supporter of Dolan’s. Dudley and his men simply did nothing to prevent McSween’s home being razed to the ground. McSween himself was shot dead with four other men as the remnants of the Regulators managed to flee the area. One survivor was Billy who swiftly took command of the remaining Regulators. Anarchy ruled as gunmen on both sides settled personal scores.

The Federal Government eventually intervened, dismissing New Mexico’s Governor Samuel Axtell, one of Dolan’s allies. Former General Lew Wallace ( veteran of the Civil War and author of Ben Hur) replaced him. Wallace lost no time in proclaiming a state of insurrection, adopting the harshest methods to restore order and end the perpetual violence. Outlaws could expect swift justice if they were caught and to be shot where they stood if they resisted arrest. Many found themselves in Lincoln awaiting trial with little chance of cheating the hangman.

With the end of the Lincoln County War, Billy had to resort to full-time crime. As a notorious participant he had no chance of legitimate work and, the longer he stayed around New Mexico, the shorter his chances of survival. After the Lincoln County War ended Billy became a brazen thief, cattle rustler and permanent annoyance to powerful and influential people.

At first Wallace’s tough stance seemed to work reasonably well, but the war began again with the murder of lawyer Huston Chapman in February 1879. Chapman had been an ally of Tunstall and McSween and was murdered by a gang of drunken cowboys seemingly for no apparent reason. The killing looked like re-igniting the war and Governor Wallace, frustrated and infuriated by his failure to capture or kill Billy, allegedly struck a secret deal with him. The controversy over that deal, assuming it was ever actually made, continues even today.

It’s alleged that, in return for his testimony against Chapman’s killers (one of whom just happened to be Jimmy Dolan) Wallace promised Billy a pardon which would have set him free. After his testimony, Billy could have ridden out of Lincoln a free man on condition that he never re-enter New Mexico. Billy’s alternative was to be hunted down and, more than likely, shot on sight. To guard against reprisals, there would be an arrest staged for Billy’s protection as being in jail would keep the Dolan gunmen from killing him after he gave evidence. If this precise offer was indeed made, then Billy took it and found himself in the Lincoln jail ostensibly to stand trial himself for murder.

District Attorney Ryerson had other ideas. Ryerson was an Irishman very much in the Dolan camp. He also had absolute discretion over which witnesses testified at trials and Billy that, as he was in custody already, would be tried for murdering Sheriff Brady. Governor Wallace was, practically speaking, powerless. Despite being the governor his hands were virtually tied by the powerful block of pro-Dolan politicians among the Santa Fe Ring. If he really did promise Billy a pardon for his testimony he was to stop Ryerson prosecuting Billy for his own part in the Lincoln County War and either declining to prosecute Dolan or deliberately throwing the case if he so chose.

Wallace was powerless and Billy was in very serious trouble. He promptly escaped from Lincoln and was free to continue his criminal career. He was now one of the most wanted men in New Mexico and, lacking any chance of legitimate work, returned to rustling and horse theft for his living. Fickle as public opinion usually is, Billy’s popularity swiftly faded into general loathing as, together with the few surviving Regulators, he roamed Lincoln County robbing and rustling at will. His activities quickly attracted the attention of powerful enemies, notably legendary cattle baron John Chisum.

In November of 1880 Pat Garrett was elected Lincoln County Sheriff. His campaign was backed by the cattle barons and their political allies who believed Billy would be a problem as long as he remained alive. In return for their supporting his election Garrett agreed to make eliminating Billy his top priority.

Garrett was a curious character, a former buffalo hunter and (some say) cattle rustler. Despite the popular impression that he was formerly one of Billy’s closest friends (one of many unsupported myths about Billy’s life and career) no solid evidence confirms Garrett and Billy were ever more than occasional acquaintances at best. Nothing supports ideas that Garrett rode with Billy or ever committed any crimes beside him. More likely, he saw a chance of lasting personal fame from being known for killing Billy the Kid, seeking to parlay that fame into a lucrative career as a celebrity lawman in the manner of ‘Wild Bill’ Hickok and later Wyatt Earp.

Garrett assembled a posse of tough, ruthless gunmen and set to work. At what became known as the Battle of Stinking Springs in November of 1880, Garrett’s posse killed Tom Folliard and Charley Bowdre, two of Billy’s closest friends. Billy was forced to surrender. He was held at Santa Fe for several months and then moved to the town of Mesilla to stand trial murdering Sheriff Brady. He was tried for the Brady murder, convicted and sentenced to death before being moved from Mesilla to Lincoln where he was to publicly hang.

Desperate problems require desperate measures. Billy took the most desperate. On April 28, 1881, only 15 days before his execution date, Billy escaped from the Lincoln County Jail by slipping his shackles and obtaining a gun smuggled to him by an admirer. While escaping he encountered the two deputies assigned to guard him, Deputies Ollinger and Bell. He shot them both dead.

Despite repeated warnings from Garrett never to let their guard drop even for a moment, both men did so and their carelessness proved fatal. After the murders Billy stood and made a speech for some 20 minutes (as if trying to justify their deaths) before stealing a horse, riding away and later forcing a local blacksmith to remove the remains of his manacles.

Everybody expected Billy to flee south into Old Mexico outside U.S legal jurisdiction. He didn’t. Garrett didn’t restart his hunt for Billy until it became apparent Billy was still within Garrett’s jurisdiction, hiding at Fort Sumner around 150 miles northeast of Lincoln itself. Garrett found Billy had taken up with local woman, Paulita Maxwell. Peter Maxwell (Paulita’s father) wanted her relationship with Billy terminated and Garrett (under pressure to keep his bargain with the cattle barons) was happy to oblige.

If terminating Billy’s relationship ended his career and life with it then Garrett was fully prepared to do the job. It was July 14, 1881, a month short of four years since the killing of Windy Cahill, when Garrett finally got his chance. Shortly after midnight at the Maxwell residence Billy came downstairs to fix a late meal. As he walked into a darkened room he realized that he had unexpected company. Peering around he asked in Spanish “Como Estas?” (“Who’s there?”).

It was Garrett. Only Garrett and Billy ever really knew whether Garrett gave Billy any warning or chance, or simply shot him dead where he stood. Was it an attempted arrest or a cold-blooded ambush? There was a bright flash, a deafening bang and a bullet tore into Billy’s head, killing him instantly. He was only 21 years old when he was buried beside old friends Tom Folliard and Charley Bowdre. Aside from their names, the three men have only a single word on their shared tombstone: “Pals.”

Assuming, that is, that he really was buried there. ‘Brushy Bill’ Roberts did claim decades later that he was Billy and that he had survived his outlaw career and that Garrett had obviously shot the wrong man and would never admit it. Several people who knew Billy supported his claim, but it was found that Roberts had also claimed to be Jesse James as well. His claim to be the real Billy the Kid was eventually dismissed.

Where Henry McCarty’s real life ends and the legend of “Billy the Kid” begins will always be open to perpetual and often heated debate. Recently, former New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson, after much consideration, refused to grant Billy the pardon allegedly promised (and undelivered) by Lew Wallace. Governor Richardson cited the fact that, despite much anecdotal evidence of the deal being struck, there’s no solid evidence that Wallace ever offered the deal let alone reneged on it. The descendents of Pat Garrett also weighed in heavily against pardoning Billy retrospectively, claiming that it would tarnish the legacies of both Lew Wallace and their ancestor.

And Garrett? Killing Billy didn’t bring Garrett the fame he seems to have craved and didn’t bring much fortune, either. His book on the manhunt titled The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid was a commercial failure seldom more authentic than the dime novels so popular at the time. Garrett was less than popular among some New Mexicans and he seems to have drifted from job to job without ever successfully capitalizing on the fame that killing Billy brought him.

Part of his failure lay in his own personality. Garrett developed a reputation; increasingly arrogant, difficult, abrasive and confrontational. As his life went on, he also developed a severe alcohol problem which did little to make him more likeable. He may not have been the most likeable person to start with.

Eventually, Garrett died in 1901. Old, ill, broke and increasingly desperate, he was killed by Jim “The Killer” Miller, a known assassin and gunfighter. Miller and Garrett had exchanged harsh words that swiftly turned to blows. Miller claimed that Garrett attempted to reach for Miller’s gun and was accidentally shot during the struggle. It was also claimed that an unknown client had hired Miller specifically to kill Garrett and make it resemble an accident or a fair fight. Either way, Garrett died having never really achieved the lasting fame and commercial success he wanted.

Leave a Reply