Your cart is currently empty!

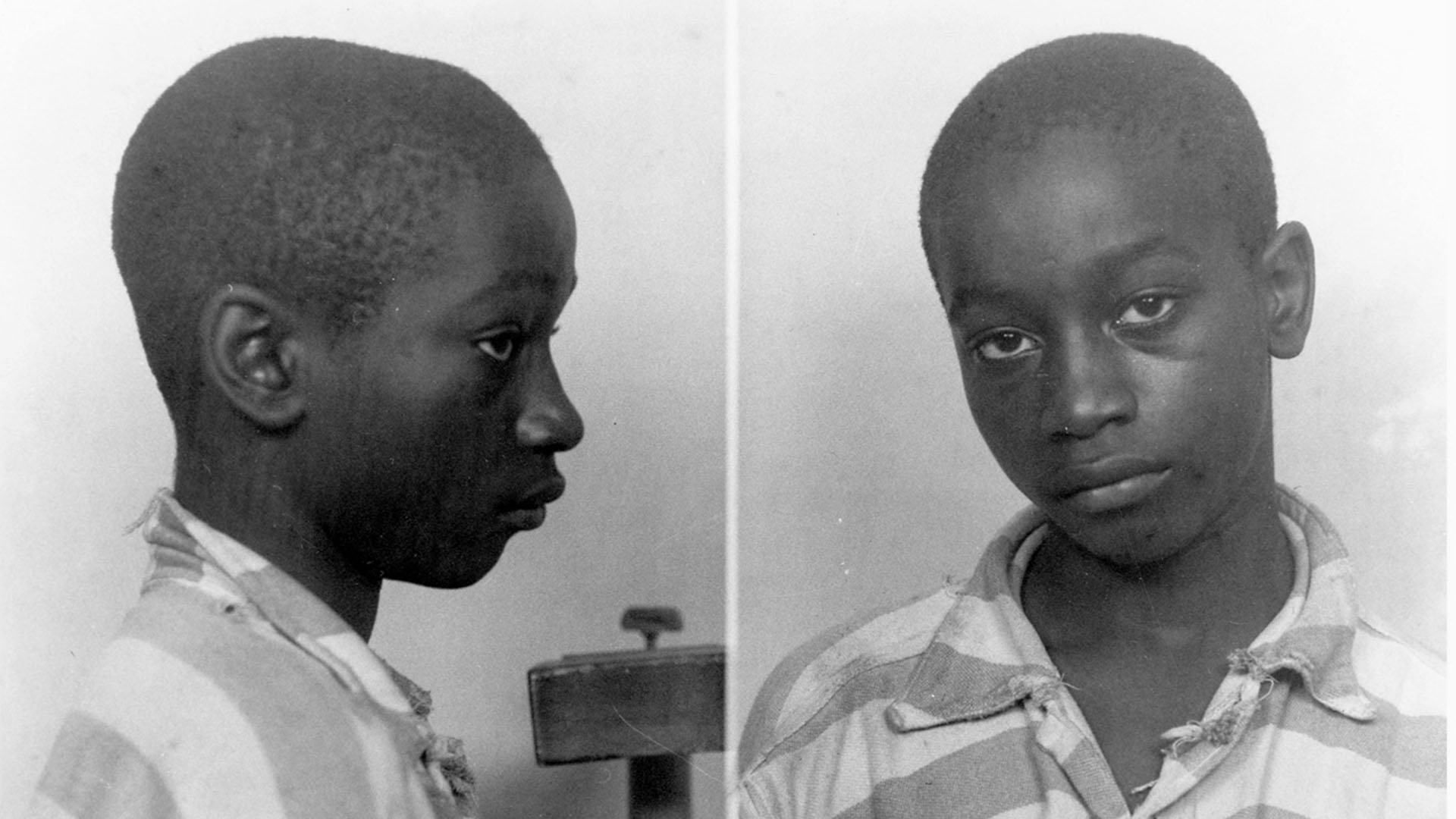

George Stinney, a stain on American justice.

The case of George Junius Stinney could easily be described as a stain on American justice, or the lack thereof. Stinney was executed in South Carolina’s electric chair in 1944 aged only 14, the youngest American to face execution in the 20th century. His confession was probably coerced, his trial a travesty of justice and his…

The case of George Junius Stinney could easily be described as a stain on American justice, or the lack thereof. Stinney was executed in South Carolina’s electric chair in 1944 aged only 14, the youngest American to face execution in the 20th century. His confession was probably coerced, his trial a travesty of justice and his execution botched, not least because he was a mere child dying in an electric chair designed for an adult. All in all, George Stinney’s original trial and execution made a mockery of the claim of ‘Justice for all’, at least until his conviction was finally overturned. It was overturned 70 years too late to save him from an untimely, unjust and unnatural death.

It was on March 23, 1944 that his path to South Carolina’s death chamber began. The bodies of two young girls, 11-year old Betty June Binnicker and 8-year old Mary Emma Thames, were found near railroad lines in the town of Alcolu. They had been beaten to death and Betty June Binnicker had been sexually assaulted. It was a brutal, vicious crime and their race makes no difference. Unfortunately for 14-year old local boy George Stinney, the fact that he was African-American in 1940’s South Carolina and accused of the sexually-motivated murder of two white children, very much did make a difference.

Search parties had been combing the area looking for the two girls after they had been declared missing. When their bodies were discovered the local people felt at first disbelief, then grief, then anger. That anger needed an outlet and, unfortunately in those more prejudiced times, George Stinney fit the bill. He was arrested on suspicion of their murder as the girls knew him. They’d also stopped by the Stinney home on the day of the murders, making the Stinneys among the last people to see them alive. Except, of course, for their murderer.

George was soon under suspicion amid a town filled with grief-stricken, angry, vengeful townsfolk who wanted the murderer caught and punished. Given that this was an especially appalling crime there was unanimity in the area as to how the killer should be punished. Nobody would be satisfied until, and unless, their killer found themselves walking their last mile to ride the lightning. South Carolina used its electric chair very regularly during the 1930’s and 1940’s often, it has to be said, against African-Americans convicted of crimes against whites. Unfortunately, apart from George Stinney’s age, there was little to separate him from many other black Americans who fell victim to racial prejudice dressed up as justice and law.

When police arrested him he quickly confessed to committing both the murders and, according to police, he also led them to the murder weapon, a 15-inch railroad spike. Unfortunately, using a heavy object like a railroad spike to inflict multiple fatal injuries in a sustained beating generally means an attacker of considerable strength and size. It doesn’t usually mean a 14-year old who stood only five feet and one inch tall and only weighed just over ninety pounds. Unless he happens to be black and in South Carolina when Jim Crow tended to have more stroke than the Constitution.

Again, George Stinney fit the bill. It wasn’t long before he was facing trial as an adult for a double child murder. Not only that, he was facing the electric chair. He was also facing certain trial and probable execution with almost no support from his family. His father had lost his job when George was arrested and, seeking employment and a chance to escape the fury of local people, the rest of Stinney’s family had departed for their own good.

Even the most sober and cool-minded observer would be forced to say that, by modern standards and by standards of justice and common decency, George Stinney’s trial was a farce. From jury selection to sentencing took less than a day. The jury was composed entirely of white jurors. South Carolina drew its jurors entirely from lists of registered voters at the time so, with African-Americans being disenfranchised, all-white juries were very much the norm. With an all-white jury in 1944 South Carolina, it’s fair to say that a black defendant would have had a rough ride at the best of times. As we shall see, these weren’t to prove the best of times for George Stinney.

Judge Stoll was a typically conservative South Carolina judge by 1940’s standards. He didn’t like criminals and was particularly hostile to black ones, especially when their alleged victims were white children. If this had been a Hollywood movie then a defence lawyer of Clarence Darrow’s legendary ability would now enter the fray and, in classic Hollywood fashion, either secure an acquittal or stay the executioner’s hand mere inches from the switch. South Carolina, however, isn’t Hollywood. Nor did Stinney’s court-appointed lawyer provide a defense on a par with Clarence Darrow. In fact, he didn’t want the case in the first place. He was also standing for public office at a time when endemic racism meant defending his client properly would have ruined his chances.

With that in mind defence lawyer Charles Plowden came up with a simple strategy. He barely defended his client at all. Plowden could have challenged the only piece of evidence against Stinney, which was that police officers claimed verbally that he had confessed. There was no written or recorded evidence of his having confessed. Nothing signed, no tape recording, nothing. Only the word of the officers that Stinney had confessed, led them to the murder scene and showed them the murder weapon. All of which George Stinney himself later denied. He admitted initially that he’d committed the crime, but retracted his ‘confession’ and claimed that he’d been bullied into giving it in the first place.

Plowden didn’t challenge the claims of a confession, even though there was no material evidence of one. He didn’t challenge the word of a single prosecution witness. He raised no objections whatsoever during the trial. Instead, his idea of a defense was to claim that, by virtue of his age, George Stinney couldn’t be considered responsible for his actions because he was only 14. For the prosecution it was a walk-over because Plowden seemed as anxious to avoid properly defending Stinney as much as prosecutors were determined to convict him.

And convict him they did. The jury were sent out to render a verdict after a trial lasting less than three hours from start to finish. The jury took only ten minutes to reach a verdict: Guilty as charged, with no recommendation for mercy. For so dreadful a crime there could only be one sentence and Judge Stoll lost no time in passing it; Death by electrocution.

Plowden’s final contribution to George Stinney’s defense was even worse than his conduct during the trial itself. Under State law at that time, any condemned inmate was entitled to one mandatory stay of execution pending appeal. Their lawyer simply wrote a single sentence on a piece of paper, signed it and a stay was automatically issued. At least, it’s issued if the lawyer doesn’t demand $500 for writing it when they know their client has absolutely no way of paying. That was exactly what Plowden did and it sealed Stinney’s fate. An execution date was set; June 16, 1944. George Stinney, now Death Row Inmate 260 at South Carolina’s Central Correctional Institution, was on the fast-track to becoming the youngest executed American of the 20th century.

There were some who felt otherwise. The NAACP, trade unionists from the CIO, concerned citizens and others wrote to Governor Olin Johnston requesting clemency and that Stinney’s death sentence be commuted to life imprisonment. Others were equally firm in demanding Stinney’s execution. Johnston was expecting to fight a re-election campaign later that year and faced a dilemma. He could commute Stinney’s sentence to life and face the ire of South Carolina’s voters, all of whom were white. Or he could allow the execution to proceed and preserve his majority at the price of his conscience. He chose the latter. He declined to interfere, saving his political aspirations and, in the process, dooming South Carolina’s youngest condemned prisoner.

The execution of a mere child was expected by all involved to be a grim affair. It was every bit as grim as expected. George Stinney walked his last mile on June 16, 1944. Of course, the wider world, given the battles in Normandy at that time, had bigger fish to fry. Prison staff, did not. In fact their fish was decidedly smaller than usual.

Like all electric chairs the one in South Carolina was designed for adults. Stinney standing only five, one inch and weighing just over ninety pounds, wasn’t an adult. Straight away there were problems, not least his lack of height. Before he sat in Old Sparky books had to piled on the seat so that the head electrode could be securely attached. The chair was too large, which left guards having to tie his arms down instead of properly buckling the straps as the leather had no holes punched in the right place to properly strap him down. But, eventually, Stinney was seated, the straps were tied and the lethal helmet positioned. All that remained was for the Warden to give the signal. He did so at 7:30pm.

2400 volts ripped through Stinney’s body as the executioner threw the switch. The leather face mask, too large for his small head, slipped off. It revealed his face, tears running down his cheeks, eyes bulging. Then his left arm came free as the arm strap loosened, his arm waving in front of the witnesses as the current surged through his body. For two full minutes, George Stinney trembled in Old Sparky’s lap, eyes streaming, face contorted and arm waving before horrified witnesses. At the end of that two minutes George Stinney was mercifully pronounced dead after only one cycle of electricity.

He lay in his grave almost forgotten until 2004 when local historian George Frierson discovered his case. Appalled by the injustice meted out, he began to gather more information and more support for having the case reviewed. Lawyers and researchers agreed to work for free, sifting through old documents and archives. On October 25, 2013 they had enough evidence to file a motion demanding the Stinney case be reopened on the grounds of a miscarriage of justice.

After hearing from both sides Circuit Court Judge Carmen Mullen agreed. Judge Mullen’s ruling exonerated George Stinney, citing the absence of a meaningful defence, the paucity of the evidence, the strong possibility that Stinney’s confession had indeed been forced out of him and that his treatment violated his Constitutional rights under the Sixth Amendment. Finally, 70 years too late to save him from an unjust and unnatural death, George Stinney was declared innocent. He lies in the appropriately-named Calvary Baptist Church Cemetery in Paxville, South Carolina. The inscription on his tombstone reads simply:

‘Wrongfully convicted, illegally executed by South Carolina.’

Frierson has alleged further misconduct in the Stinney case. In interviews Frierson has claimed that the real murderer was a member of a prominent local family. A prominent white local family. He also claims that the person in question, now deceased, made a deathbed confession to the crime for which George Stinney unjustly met his death. He goes even further, stating that at least one other member of that family was on the coroner’s jury that recommended George Stinney face trial for the murders.

The relatives of Betty June Binnicker and Mary Emma Thame, on the other hand, beg to differ. They are still firmly convinced of Stinney’s guilt, believing that the claim of a deathbed confession has never been substantiated. The balance of probability and the test of reasonable doubt suggest, with all due respect, that they are wrong. That said, while much has been made, and rightly so, of the mistreatment and injustice of George Stinney’s case, we mustn’t forget that two innocent young girls were brutally murdered for seemingly no reason other than being in the wrong place at the wrong time and meeting the wrong person.

May they –George Stinney and their families– eventually find peace.

2 responses to “George Stinney, a stain on American justice.”

-

[…] In fact New York’s so-called ‘Death Commission‘ that originally recommended the electric chair as a replacement for the gallows specifically discarded lethal injection for reasons similar to its critics today. It seems South Carolina has learned little from their example. Or that of a certain George Stinney. […]

-

Reblogged this on Crimescribe.

Leave a Reply