Your cart is currently empty!

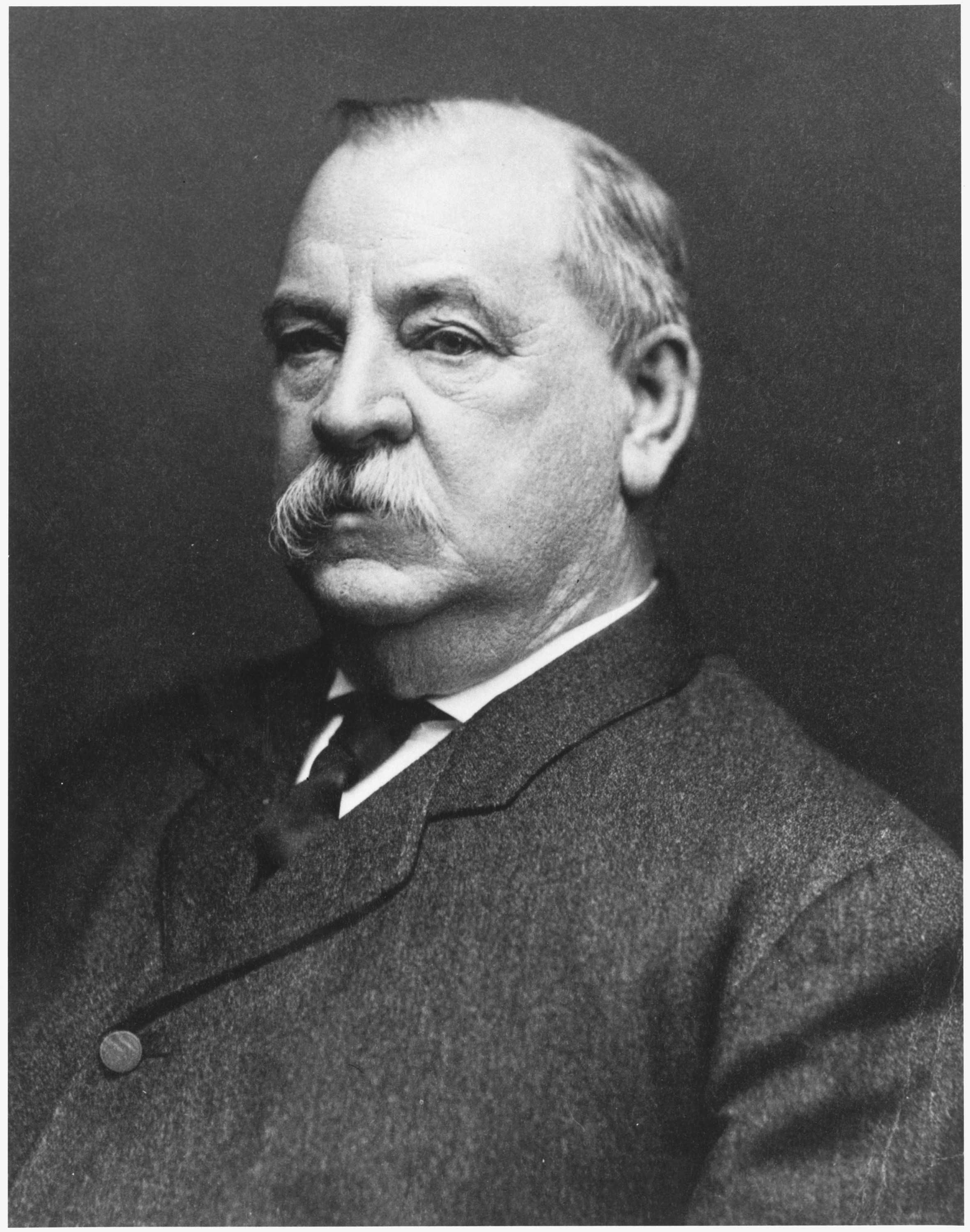

On This Day in 1873 – John Gaffney hanged by future President Grover Cleveland.

A free chapter from ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York.’ Grover Cleveland is seldom regarded as an exceptional US President. He wasn’t universally despised (although often deeply unpopular) but not universally admired either. In short, he was a safe and unspectacular pair of hands. He does have one singular attribute setting him apart from…

A free chapter from ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York.’

Grover Cleveland is seldom regarded as an exceptional US President. He wasn’t universally despised (although often deeply unpopular) but not universally admired either. In short, he was a safe and unspectacular pair of hands. He does have one singular attribute setting him apart from every other man to enter the White House. Grover Cleveland served as America’s 22nd and 24th President of the United States, the only President to serve non-consecutive terms. He remains the only former executioner ever to enter the White House.

While Sheriff of Erie County in 1872 he hanged murderer Patrick Morrissey and in 1873 murderer, John Gaffney. Morrissey and Gaffney were and still are America’s only felons to be personally executed by a President.

At the time aspiring New York politicians often reached the White House by an established route. They involved themselves in local politics, were elected as County Sheriff and possibly District Attorney, worked their way up to State Governor and from there ran for President. Cleveland, elected Erie County Sheriff in 1871, hadn’t initially wanted the job. He was already practicing law and had little interest in politics.

Cleveland’s friends in the Democratic Party wanted him to run based on his honesty, integrity and sense of public service. At the time corruption was everywhere and Erie County was no exception. The Democrats wanted a new broom to clean up Erie County and saw Cleveland as perfect for the job. He also had a family to support on little money and County Sheriff was a highly-paid position. Needing the money and possibly more interested in politics than he realised, he reluctantly accepted the nomination.

He would run things his way, he told them. He would not be obligated to anybody, do political favours or anything that might compromise the integrity of his office and himself. He would apply the letter of the law without fear or favour and discharge every duty expected of him. According to him: “Public officers are the servants and agents of the people, to execute the laws which the people have made.”

It wasn’t long before his resolve was tested to the limit. Enter Patrick Morrissey and John Gaffney. One of the Erie County Sheriff’s duties was to act as the county’s executioner. Until New York State took full responsibility felons died in their county of conviction and County Sheriffs were officially and personally responsible. In practice they usually employed substitutes to do the actual hanging. During his two terms Sheriff Cleveland’s predecessor had employed Deputy Jacob Emerick, but Emerick had already had enough.

For years Emerick had endured public scorn. People called him ‘Hangman Jack’ and ‘Hangman Emerick’ even to his face. They didn’t mind seeing his hand pull the lever, but they didn’t want to shake it when they met him. Emerick’s family also suffered. After years of increasing isolation, public disapproval and general abuse Emerick wanted out. The $10 for each hanging simply didn’t cover the social and personal damage to himself and his family.

Cleveland was sympathetic. A local man, he knew full well of Emerick’s problem and his declining social status. If Emerick didn’t want the job then he didn’t have to do it. Remembering his own vow to fulfil every aspect of his official duties, Cleveland knew what that meant. He would have to pull the hangman’s lever himself. As Cleveland put it; “Jake and his family have as much right to enjoy public respect as I have, and I am not going to add to the weight that has already brought him close to public execration.”

Cleveland had already surprised many of his contemporaries by accepting the nomination for Erie County Sheriff in the first place. His being prepared to personally perform the worst aspect of the job surprised them still further. Surely even Cleveland, widely known for his strong sense of duty, honesty and integrity, wouldn’t take on so grim a task when he didn’t have to.

They were wrong. As distasteful as they were executions were still part of Sheriff Cleveland’s job description. Even if Emerick had been prepared to continue doing the Sheriff’s task for him, the Sheriff wasn’t going to let him. To Cleveland it was simply a matter of duty; it was his responsibility and his alone. Much to Emerick’s delight he was relieved of any further involvement. ‘Hangman Jack’ was replaced by the Sheriff known throughout Buffalo as ‘Big Steve.’

It wasn’t to the relief of Patrick Morrissey. Twenty-eight years old, a sailor, drifter, drunkard and some-time felon, Morrissey wasn’t what anyone would call respectable. Born in County Tipperary, Ireland, Morrissey had already served three years in Auburn Prison for larceny and spent six months in a juvenile home. He drank heavily and married his second wife having deserted and divorced his first. His second wife wasn’t even in the US, Morrissey having married her while on a trip to Liverpool, England.

Morrissey’s father had died when he was a boy, leaving him and his siblings with their mother. Known to be violent and aggressive when sober and even worse when drunk, it was said at his murder trial that none of her children escaped lasting damage at her hands. She in turn suffered fatal damage at Patrick’s. On 23 June 1871 he arrived home heavily intoxicated. A domestic altercation quickly got out of hand leaving her dead in her own kitchen, a knife embedded in her body.

Patrick, perhaps realising what he’d done only after he’d done it, didn’t try to run. He was immediately arrested and charged with murder. If convicted, and he was, a mandatory death sentence awaited him. In today’s courts he might have been sent to prison for manslaughter or second-degree murder, but the jury in 1871 saw things differently. Swiftly tried, convicted and condemned, Morrissey was lodged in the Erie County Jail to await execution. Cleveland, later known as the ‘Buffalo Hangman,’ was told to make the arrangements.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Morrissey attracted some measure of public sympathy. Two of his sisters swore that their mother had a violent, uncontrollable temper and a fondness for liquor. Morrissey himself claimed he didn’t remember having stabbed his mother. He was young, drunk and, confronted by yet another of his mother’s violent episodes might have simply snapped.

It made no difference. Efforts were made to secure either a commutation or executive clemency, but the courts refused to intervene. New York’s Governor John Thompson Hoffman wasn’t swayed either. Morrissey’s would be the last of eight hangings performed during Hoffman’s tenure and Morrissey lacked the influence, public support or connections to change his mind. Morrissey’s execution was scheduled for noon on 6 September 1872.

Cleveland prepared thoroughly. Not only did he want his first hanging to be a success with minimal suffering for all involved, he was determined that it should remain a private affair. Only fifty people would be there to watch Patrick Morrissey die. That was a large number by modern standards but still a far cry from the unrest, drunkenness and debauchery typical at public executions.

Public executions had long been abolished in New York State. Morrissey would die on a scaffold erected in the east wing of the jail yard. Within its walls Cleveland hoped to keep the event from becoming too public. A large awning was erected around the gallows. Carefully positioned, the awning would block any views from nearby trees or rooftops.

Cleveland knew full well that morbid sightseers would take any chance available to watch Morrissey hang. He also knew that, without the awning, choice viewing spots would be sold to anyone with money to spend and the desire to watch someone die. He was determined to deny them that ghoulish opportunity.

As the days passed Morrissey, contrite and guilt-ridden, was a model prisoner. An Irish Catholic, he spent his last night with priests and nuns from the Sisters of Charity. They stayed until one in the morning when Morrissey went to bed for the last time, sleeping soundly until the morning. While he ate his last breakfast Morrissey’s three sisters and a brother-in-law came to bid him their final farewell.

Cleveland treated him firmly but also kindly. He ensured Morrissey’s final hours were spent only with those visitors he wanted to see. A half-hour before noon Cleveland allowed him to leave his cell. Going from cell door to cell door escorted by one of Cleveland’s deputies Morrissey bade his fellow inmates goodbye.

John Gaffney was one of them. The only two condemned prisoners, Morrissey and Gaffney had formed a natural rapport. As Morrissey made his final rounds he asked that Gaffney’s cell be opened for a final embrace and Cleveland allowed it. Minutes later Patrick Morrissey began walking his last mile.

Sheriff Cleveland, Erie County’s Under-Sheriff, some deputies and Morrissey’s priests escorted him on his final journey. Father Mallony offered Morrissey his arm to lean on if he needed it. Morrissey took it. Slowly but firmly the procession entered the yard and Morrissey ascended the scaffold’s traditional thirteen steps.

It was common at the time for prisoners to make a brief final speech from the scaffold and Morrissey did so. Reading aloud in a firm voice he admitted his guilt but also denied knowing what he’d done at the time of the crime. He also warned everybody of the evils of drink and bad company before bidding them a final farewell. His speech finished, Morrissey stood straight while Cleveland drew the noose around his neck and a black hood over his head.

At five minutes past twelve Cleveland sprang the trap. Dropping around seven feet Morrissey died almost immediately, his neck snapping at the end of the rope. According to other reports Cleveland bungled the drop and Morrissey died slowly from strangulation. Either way Morrissey, then the only American to be hanged by a future President, was pronounced dead thirteen minutes later. Cleveland’s job now done, he ensured Morrissey was quickly cut down and placed in a casket. Morrissey’s friends later claimed his body.

Cleveland had kept his promise and done his duty. He hadn’t done it without personal cost. A New York Times article dated 7 July 1912 ended with the words:

A few Buffalo people still live who can bear out the statement that this little tragedy made Mr. Cleveland a sick man for several days thereafter. He was not so stolid and phlegmatic as very many persons have been led to believe.

John Gaffney would live on, but not for long. The ‘Buffalo Hangman’ had one more job to do. Morrissey had been a petty criminal and dissolute drunk but he still attracted some sympathy. Gaffney was a career felon known and loathed throughout Buffalo, but his efforts to avoid the noose came far closer to succeeding. While Morrissey was keeping his date with the hangman Gaffney was working hard to avoid his own.

An important plank in Cleveland’s election campaign had been a pledge to clean up Buffalo’s notorious Canal District, probably the most violent, crime-ridden part of Buffalo if not Erie County. The period between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and 1900 is sometimes called Buffalo’s golden age but the Canal District had only been getting worse.

Burglaries and robberies were common, bar-fights and gang brawls almost an everyday event and murders kept local newspapers in business and their readers entertained. Cleveland had promised to clean up the area. Realistically there was little he could actually do in the face of corruption and political cronyism. John Gaffney proved to be a rare exception.

Gaffney was typical of Buffalo’s criminal element. Young, violent and quick to anger, he’d first gained attention in 1862 while still a juvenile. Starting with petty theft, larceny, robbery and burglary, Gaffney ran with local street gang the ‘Break-O-day Johnnies’ while still a teenager. The Johnnies, notorious for their violence and thieving, were bad for Buffalo’s image and a regular thorn in the side of local police.

Gaffney’s aggressive nature saw him commit numerous violent crimes, not all gang-related. He was a street thug, thief, bully and general trouble-maker well-known to Buffalo police. When he hadn’t been stealing and brawling Gaffney’s rap sheet including a stabbing, two shootings, and an attempted shooting, waving a pistol at a police officer and smashing a man over the head with a paving slab.

He didn’t confine his violence to the streets, either. Now on his second marriage, his first wife had blamed him for the injuries that caused her death. Delivered on her death-bed, the accusation hadn’t been enough evidence to charge her husband. After her death Gaffney had remarried and gone into business running the Metropolitan Concert Saloon.

Between 1866 and 1872 Gaffney had been charged with riot and petty larceny, also accumulating a dozen arrests for assault and battery and disorderly conduct. Not all his crimes had improved his tough-guy image, though. On one occasion while attempting to shoot another passenger aboard the steamship Ivanhoe, Gaffney had somehow managed to shoot himself instead.

His violent reputation might have caused most of his troubles, but also provided some protection. In 1867 he’d fired a pistol through the window of a Buffalo home hitting Rosa Kilbride in her hip. Despite the serious injury Kilbride refused to testify. She knew full well Gaffney would willingly inflict far worse if she did. In 1871 Gaffney subjected Frank Haley to a particularly vicious assault but Haley, also knowing Gaffney’s reputation, wouldn’t testify.

On 7 May 1872 Gaffney’s mean streak was finally his undoing. Murdering fellow Canal District thug Patrick Fahey earned John Gaffney an unwilling place in criminal history and a date with the hangman. Fahey, every bit as thuggish as Gaffney, wasn’t averse to starting entirely needless saloon brawls to liven up an evening. Saloon owner Gaffney was incensed when Fahey chose the Metropolitan for an evening’s brawling.

Fahey had wrecked the Metropolitan one night and driven away a lot of good, regular customers in the process. Gaffney was furious, facing large repair bills and a shortfall in profits. That in turn caused an altercation costing both thugs their lives. It was no secret that Gaffney and Fahey were going to come to blows sooner or later, a question of when they settled accounts rather than if. Gaffney and his cronies were drinking and playing cards at Sweeney’s Saloon when Fahey walked in. Trouble started almost immediately and mutual insults were quickly exchanged.

Gaffney, true to his reputation, drew a revolver and tried to pistol-whip Fahey. Fahey quickly tried to get away and Gaffney, whose aim had improved since the Ivanhoe incident, promptly fired three shots at his fleeing enemy. As Fahey made for the door two of them hit him in the jaw and the left side of his body. Patrick Fahey died shortly afterward.

He survived long enough for police officers James Shepard and Patrick Shea to ask him a few questions. Responding to the gunfire Shea and Shepard knew Fahey as a local thug and didn’t like him. They also knew John Gaffney and liked him even less. Regardless of their contempt for Fahey, who’d been a regular problem for local police, they immediately went in search of his killer.

In the Canal District this wasn’t as easy as it might seem. Locals were often hostile to the police or too afraid of local criminals (especially ones like Gaffney) to testify. If in doubt they saw nothing and heard nothing. If they valued their health they also said nothing. Not surprisingly initial questioning provided a steady stream of witnesses claiming they had witnessed nothing at all.

Shea and Shepard weren’t so easily deterred. Returning to their precinct they spoke to Captain Edward Frawley, also well aware of Gaffney and Fahey. With other officers Shea and Shepard returned to the area rounding up several potential witnesses as they went. Gaffney, whose aim had been true but whose common sense had seemingly deserted him, hadn’t quite fled the area. He was picked up in another local tavern instead.

When Coroner Vaughn began his inquest numerous witnesses were called to testify. True to Canal District form almost all of them had no evidence to offer. Bartender Patrick Sweeney had been asleep behind the bar at Sweeney’s when Fahey was shot. Customer John Grandison, so he claimed, had played cards with Gaffney at Sweeney’s but gone to another tavern before the shooting.

Fellow card-player Edward Gaynor said the shots had come from outside Sweeney’s, not inside. Gaffney’s brother-in-law ‘Red Jack’ Farrell (another local hoodlum) claimed to have heard shots fired, but not seen anything. Customer Samuel McElrath, according to McElrath himself, had been too drunk to remember anything at all.

By then Gaffney probably thought he was in the clear. Had one witness not actually spoken out he probably would have been. Local singer Alexander McQuinnay (known locally as ‘James Quinn’) hadn’t intended to talk either. A night of intensive police interrogation quickly changed his mind. McQuinnay knew all there was to know and told it all at the inquest. Gaffney’s goose was cooked from then on.

McQuinnay had dropped by Sweeney’s to play cards with Gaffney. He wasn’t one of Gaffney’s regular acquaintances but knew him well enough for cards and a few drinks. He described everything he’d seen when Fahey and Gaffney had fought and Gaffney was finished. The twelve men on the Coroners’ Jury named Gaffney as Patrick Fahey’s killer. He was immediately arrested and held for trial. If convicted John Gaffney would almost certainly hang.

Gaffney’s trial jury found the same with one crucial difference. At the time Coroner’s Jury could issue a finding of murder and name the alleged killer, but not apply a sentence. A trial jury could apply a sentence and under New York law at the time it could only apply one. With Judge Isaac A. Verplanck presiding they did exactly that. Gaffney was sent to Erie County’s jail where Patrick Morrissey was already lodged and their sentences were the same; Death by hanging.

Morrissey had died on 6 September 1872 bidding Gaffney a tearful farewell as he went. Morrissey, contrite and guilt-ridden, might have gone willingly to his fate. Gaffney was determined to avoid Cleveland’s noose and wouldn’t go as quietly. Originally slated to die on September 21 only three weeks after Morrissey, Gaffney began an intense and entirely false campaign to be ruled insane and cheat the hangman.

His legal avenues were soon exhausted and new Governor John Adams Dix was unlikely to intervene. Gaffney’s was to be the first of five New York executions performed during Dix’s tenure. With that in mind Gaffney saw an insanity ruling as a slim chance to swap a straitjacket for the hangman’s noose. Given his predicament a slim chance was better than none. He also knew that death sentences had been commuted for crimes far worse than his.

For a man perhaps deserving little or no sympathy Gaffney’s campaign proved surprisingly effective. His execution date was postponed more than once as a result. His wife and friends pressed vigorously for his sentence to be commuted. The entire trial jury supported him. Nearly one hundred members of Buffalo’s Board of Supervisors and the Board of Trade supported his case. Still no commutation was forthcoming. Knowing his options were increasingly limited and with time running out Gaffney began to go ‘insane.’

Combining random chatter, gibberish and nonsensical ramblings with surprisingly lucid, coherent pleas for mercy caused further delays. Cleveland himself postponed Gaffney’s execution for a week so he could have Gaffney psychiatrically examined. Unable to agree on Gaffney’s mental health the experts unwittingly earned Gaffney yet another delay, but not a commutation. A jury of inquiry finally closed the book on the matter, ruling unanimously that Gaffney was sane under the law. With all hope now gone Gaffney, perhaps tired of his charade, admitted it was all a sham.

14 February 1873 dawned cold and icy. So icy was it that salt had to be sprinkled around the scaffold for the safety of the execution party as they climbed the scaffold steps. Gaffney’s final visits were from his family, friends and religious advisors. Unable to sleep through his final night as Morrissey had done Gaffney still managed a light breakfast of poached eggs, toast and coffee.

Before his execution Gaffney gave his son a few parting words:

Johnny, Papa’s going to die, and I want you to promise me these things, that you will not drink any spirituous liquors, that you will never play cards, that you will never swear, and never break the Sabbath, that you will go to Church and Sunday School, that you will not be out nights and keep bad company, as Papa has done.

After final meetings with friends, relatives and priests Gaffney’s time had come. Escorted by Cleveland, the Under-Sheriff, some deputies and priests Gaffney stepped out into the jail yard. Like everyone present his breath steamed in the noon air as he ascended the scaffold wearing a black gown and cap. A Catholic like Morrissey, Gaffney bore a crucifix in his hands and mounted the scaffold steadily and firmly. Ignoring the protestations of the priests he exercised his traditional right to a farewell speech.

Admitting his guilt and blaming his crime on alcohol, Gaffney also blamed ‘Red Jack’ Farrell for slipping him the revolver in Sweeney’s saloon. If he was hoping for a last-minute stay while the accusation was investigated Gaffney was disappointed. He finished with a short prayer:

I hope and pray to God that you will believe me and forgive me. I beg pardon for all the crime I have done, and I forgive all who have injured me.

At the end of his speech Cleveland applied the noose and black hood before slipping behind a screen hiding him from view. As he had done with Patrick Morrissey, Cleveland immediately jerked the lever. With a loud crash the trapdoors opened and Gaffney dropped out of sight. His neck instantly snapped while the crucifix remained clasped between his hands. Twenty-three minutes later he was formally declared dead.

With Morrissey and Gaffney gone to join their victims Grover Cleveland’s career as an executioner ended. After serving only one term as Erie County Sheriff he returned to practising law at the end of 1873. Elected President in 1885 he served his first term, succeeded in 1889 by Benjamin Harrison. Regaining the Presidency in 1894 made him the only President to serve non-consecutive terms.

During his Presidential campaigns Cleveland’s past returned to haunt him. Once known to Buffalo’s residents as ‘Big Steve,’ Cleveland’s opponents started calling him the ‘Buffalo Hangman.’ They openly questioned whether a former executioner deserved to be President although American voters didn’t seem to mind. The irony of politicians using law and order to win votes while using Cleveland’s penal past against him probably hadn’t escaped them.

It wasn’t Cleveland’s last encounter with the death penalty, either. While Governor of New York from 1883 to 1885 Michael McGloin, Pasquale Majone, William Ostrander, Edward Hovey and Charles Clarke were hanged. As Governor Cleveland had to decide whether to spare them the punishment he’d personally inflicted as Sheriff of Erie County. First-hand experience probably didn’t make that task any easier. His first Presidential term also coincided with New York State’s last female hanging, that of Roxalana Druse in February 1887.

Cleveland’s second term as President ran from 1893 to 1897. Succeeded by William McKinley, McKinley was shot in Buffalo at the Pan-American Exposition on 6 September 1901 by Leon Czolgosz. Killed as much by inept medical care as Czolgosz’s bullet McKinley died of infection on 14 September. With the gallows now replaced by the electric chair Czolgosz was electrocuted at Auburn Prison on 29 October only weeks after McKinley’s death. ’

One response to “On This Day in 1873 – John Gaffney hanged by future President Grover Cleveland.”

-

[…] only catch was that Cleveland would have had to have paid the deputy $10 for the act. Grover was a renowned penny pincher throughout his life, and the thought of paying $10 for another man to do his job didn’t sit well with him. So, […]

Leave a Reply