Your cart is currently empty!

1954, a mass break-out from Sing Sing’s Death House (almost) and Sing Sing’s last ‘triple-hitter.’

Rosario, believing he had done enough to catch the right eyes, awaited his clemency and heard nothing. There was no more ominous silence than when a Governor was considering clemency, it usually meant there wouldn’t be any.

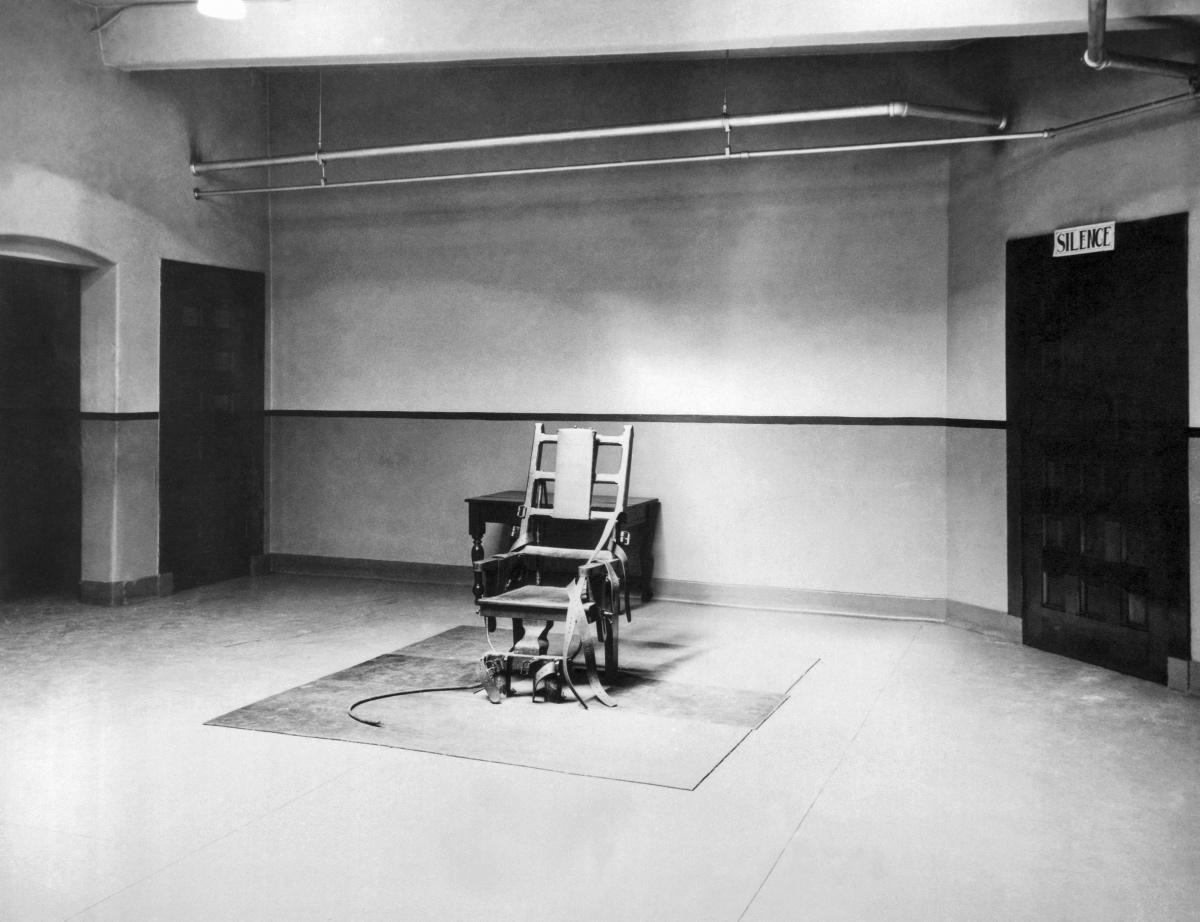

By 1954 New York’s death penalty was in decline. Long gone were the days when almost twenty prisoners a year walked their last mile and exited through the ‘little green door’ never to return. By the mid-1950’s the annual average was down to half-dozen or so, a shadow of the Roaring Twenties and Depression years when occupied cells became vacant on an almost-weekly basis. Killers still killed, juries still convicted and judges still condemned but Dow Hover (appointed in 1953 after the sudden resignation of Joseph Francel) was New York’s last and least-employed State Electrician.

By the time condemned killer Romulo Rosario arrived on 14 May 1954 New York’s condemned had an increasing faith in either winning their appeals or the Governor granting clemency. They also found they had far more time to fight their cases, instead of mere months between sentencing and execution they often had years to fight their cases. Appellate judges were proving increasingly-responsive to prisoners’ pleas. Political ears, so long deaf to reform of New York’s capital punishment laws let alone abolition, had begun opening. New Yorkers themselves were increasingly questioning the morality, efficacy and even existence of their state’s death penalty.

Condemned for murdering Michael Gonzalez the previous year, Rosario had good reason to believe he might walk free from the death house and perhaps one day from Sing Sing itself. Just as the condemned feared their time running out and their last brief walk between life and death Old Sparky’s days were also numbered. Had Rosario committed his crime a decade later he would probably have avoided the death house and certainly not been executed, New York’s abolitionist movement was already making considerable headway.

Rosario would have known it and was banking on it. Just as he always maintained he had shot Gonzalez in self defence, Rosario always believed he would beat the chair. He died still believing either a judge would intervene or the Governor would call .Given his lengthy record for pimping, drug-dealing and violence Rosario was likely to need a little something extra to earn clemency. As luck would have it his fellow-condemned were on hand to give him one last opportunity to cheat the chair. They just didn’t know it yet.

Almost as soon as he arrived Rosario was embroiled in a desperate conspiracy, a plot led by convicts already closer to their dates than him. In concert with other condemned men career criminals ringleaders Calman Cooper, Nathan Wissner and Harry Stein had evolved a desperate plan to break the entire Death House roster. Their plans were both delayed and spoiled by the executions of co-conspirators Gerhard Puff, Barry Jacobs, John Dale Green and Henry Matthews. Knowing they were short-handed Green had slipped Rosario a note before Green and Jacobs were executed on 26 August 1954.

Rosario had barely been in the death house a few weeks and he already saw an opportunity. Not for escape, but for clemency. Rosario was about to sell out his fellow-convicts in a vain hope of leniency. In Rosario’s mind the two notes from Green were his tickets out of the death house, they would take him away from the electric chair and eventually Sing Sing itself.

‘It is impossible to get guns in here and we have to have guns to get away. What we are planning to do is to have the Warden’s home taken over and him used as a tool to bring my boy in with him as a visiting cop. He will have the stuff with him and we use the Warden’s family as hostages. It will only take 2 or 3 men outside and I have boy out there who knows the whole plan with the times and all the details. Are you in? It’s better than waiting around to just die like sheep. What can we lose? TEAR UP AND FLUSH IN TOILET.’

Initially, Warden Wilfred Denno was less than impressed and highly sceptical, later remarking “We get tips like this all the time.” It was a ludicrous plan involving the emptying of the death house and the assumption that Denno’s guards would simply allow the escapers to leave without shooting them to pieces before they even left the prison. That was assuming that Denno himself buckled under the pressure and agreed to help free New York State’s entire supply of condemned murderers. The word of crooks in general and condemned ones in particular is always questionable, but Rosario received support from an unlikely source; the NYPD.

Sergeant John Cottone of the NYPD’s Narcotics Squad had arrested Rosario in 1949, helped him win parole and then turned him into an informant, a reliable one. When Rosario requested a visit from a detective he felt he could trust Cottone came to see first Rosario and then Denno. Green’s note and Cottone’s recommendation finally convinced a reluctant Denno to inform the State Police. With Denno and his family under 24-hour guard and the Death House under increased security the big break-out was off.

It didn’t take long for the others to realise who had informed. There are no secrets in prisons, especially small ones like the Death House. With Rosario suddenly receiving more unidentified visitors than usual his fellow-plotters knew the game was up. Unable to get to him and kill him they could do nothing but sit, seethe and continue trying more lawful means to escape Old Sparky. Rosario, believing he had done enough to catch the right eyes, awaited his clemency and heard nothing. There was no more ominous silence than when a Governor was considering clemency, it usually meant there wouldn’t be any.

The treacherous Rosario had no idea that New York’s Governors had an unwritten law concerning clemency in capital cases, they only said anything if they were actually granting mercy. Rosario would receive as much mercy as he had granted Michael Gonzalez and hear nothing from the Governor. Death House staff lacked the heart to tell him as much. Warden Denno had no authority either to grant or even recommend clemency and didn’t feel Rosario’s snitching was enough even if he could have. With Cooper, Stein and Wissner having delayed their executions yet again since their arrival in 1950 it was no small irony that Rosario walked the last mile before they did.

On the night of 17 February 1955 Romulo Rosario was taken form one of the six pre-execution cells known as the Dance Hall. It was standard practice to remove anyone due for execution twelve hours beforehand, lodging them in the Dance Hall only thirty feet from the chair itself. If their appeals were successful or the Governor intervened they would be returned to their regular cell the next morning. If not they would leave the Death House feet first. Of the many hundreds who stayed in the Death House two-thirds walked in alive and were wheeled out dead. Rosario was one of them.

As he left for the Dance Hall Cooper, Wissner and Stein threw him a bitter farewell. It was no small satisfaction for them to know he would die before they did. With Dow Hover on hand Rosario was dead within three minutes of sitting down. Stunned by the lack of mercy for his betrayal Rosario had declined a last meal and kept on mumbling that he had shot Gonzalez in self-defence. Nobody had believed him. Instead of anything special Rosario’s last meals had been sauerkraut, frankfurters, soup and a grilled bacon sandwich.

Cooper, Wissner and Stein, however, had little time to savour their small triumph. All career criminals with lengthy records, they knew neither the courts or Governor would spare the trio known to New Yorkers as the ‘Reader’s Digest Killers.’ Murdering 83-year-old Readers Digest messenger Andrew Petrini in 1950 sealed their fate and the haul from their botched robbery had done them no good. Now they would pay the penalty.

Unlike Rosario the trio had ordered some of the usual Death House fare. It was nothing fancy, but enough to keep them happy in their final hours. None of them seemed either surprised or overly concerned as the clock wound down. Cooper and Wissner ploughed indifferently through cold chicken, shrimp salad, ice cream, coffee and cigarettes. Stein opted for Southern-fried chicken, coffee, cigarettes and ice cream. They had no expectation of mercy.

Since their arrival in December 1950 previous Governor Thomas Dewey had already turned them down. Dewey’s replacement Governor Averill Harriman (then away in Europe) had already refused. Acting-Governor George DeLuca was in no mood to anger his boss by overturning Harriman’s decision and Hover was on hand to earn another fee. He did so on 9 July 1955 only months after the hated Rosario had met his fate.

It was also Sing Sing’s last triple execution, another sign that even Old Sparky was on its way out. Singles and doubles had been standard fare at Sing Sing since the chair was installed and triples never raised an eyebrow unless one or more convicts was especially well-known. Four, five and on occasion seven convicts had been executed in a single day at one time but hose days were long over. Never again would Hover collect his standard $150 for the first convict and an extra $50 each for the other two. The era of the ‘triple-hitter’ had just ended. The reign of the State Electrician had less than a decade left to run.

One response to “1954, a mass break-out from Sing Sing’s Death House (almost) and Sing Sing’s last ‘triple-hitter.’”

-

[…] In 1916 murderer Oreste Shillitoni used a smuggled gun to escape the original Death House days before his execution date. Condemned for a triple murder, Shillitoni escaped by seriously wounding two guards and killing another. Recaptured after a few hours, he was quickly executed. With security and, to fair, some small humanity in mind, a brand-new, custom-built ‘Death House’ was called for. State Architect Lewis Pilcher designed the new facility which opened in 1922. It was unique. No other prison on Earth had a similar custom-built facility and nobody ever escaped the new Death House although some did try. […]

Leave a Reply