Your cart is currently empty!

Frank Rimieri, Adolph Koenig and Doctor Allan Mclane Hamilton – A dark day that cast a very long shadow…

When Frank Rimieri and Adolph Koenig rode the lightning at Sing Sing on 20 February 1905 that was nothing unusual in itself. First used on William Kemmler on 6 August 1890, New York’s electric chair was already seeing regular use. Single and double executions like this one were standard practice and New York, already enthralled…

When Frank Rimieri and Adolph Koenig rode the lightning at Sing Sing on 20 February 1905 that was nothing unusual in itself. First used on William Kemmler on 6 August 1890, New York’s electric chair was already seeing regular use. Single and double executions like this one were standard practice and New York, already enthralled by its new invention, hadn’t even begun to use it as regularly as it later would.

A so-called ‘double event’ already raised little attention unless one or more of the condemned had a particular notoriety. Neither Rimieri or Koenig were of any particular note, but witness Doctor Allan McLane Hamilton certainly was. In a sense Rimieri and Koenig, in theory the most important players in the morning’s drama, would become bit-part players in Hamilton’s story.

The executions of Rimieri and Koenig, though, would cast a far longer and darker shadow than anyone could have believed. Not everybody was in favour of electrocution as a means of dispensing quick, painless and reliable judicial death and Hamilton already disliked the idea of electrocution. Witnessing the reality for the first, last and only time revolted him so much that he pressed even harder for his preferred method. Hamilton was only at Sing Sing for a couple of hours, but that brief visit had lasting consequences for America’s condemned.

Doctor Allan McLane Hamilton was already a distinguished physician and, in the language of the time, an equally-distinguished ‘alienist.’ What we nowadays consider soemwhere between a psychiatrist, psychologist and profiler, Hamilton was one of the leading alienists of his time and his opinions, medical or otherwise, carried weight.

Already opposing electrocution if not capital punishment itself, Hamilton had long had a different method in mind that New York had already declined. The deaths of Rimieri and Koenig spurred his efforts to find somewhere to use it. After testifying for the defence in a civil lawsuit, Hamilton realised he needed to know more about the lethal aspects of electricity and SIng Sing was the perfect place to find out.

To quote his 1916 memoir ‘Recollections of an Alienist’:

“As the result of this experience I determined at the first opportunity to qualify myself for any subsequent appearance on the witness stand in any other possible case of this kind, and within a few months I was invited to attend an electrocution at the State’s Prison at Ossining, the hour being fixed at six o’clock in the morning.”

Hamilton’s curiosity was about to lead him into a dark place and along an even darker path, albeit unwittingly. He could never have known the consequences of that cold, grey winter morning at Sing Sing. If he had Hamilton might well have reconsidered. As it was, he didn’t. His first sight of Sing SIng’s death chamber unnerved him greatly What was to follow, although tame by Sing Sing standards, marked him for the rest of his life:

“As we entered most of the small room was in darkness, but in the centre was an ugly, cumbersome wooden chair upon which was placed a number of electric bulbs, all harmless enough in themselves, but horrible in their cuggestion that their resistance was typical of what was in store for the unfortunate who was later to take their place. The ugliness of the chair and its business-like character were striking, for no such piece of furniture could be used for anything but torture, and it forcibly called up the old wood-cuts of the Inquisition that I collect.”

The executions themselves were nothing out of the ordinary, at least not Sing Sing staff. First came scrap trader Rimieri, condemned for the senseless shooting of fellow-trader Jacob Pinto after a dispute over the ownership of some glass bottle. Rimieri’s execution was brief as his crime had been pointless. After two jolts he was dead and within minutes Adolph Koenig entered the chamber.

With wisps of smoke and burnt flesh still in the air Koenig, condemned for strangling his girlfirend after she had refused him money for alcohol, also received two jolts. Both were then carried into the small morgue adjoining the death chamber for the autopsies mandated under State law. The ‘double event’ had been and gone and Hamilton, appalled by the sight, vowed to pursue his own ideas with renewed vigour. As Hamilton himself described Koenig’s death:

“This time the killing was more difficult, and when the Warden said to the executioner “You had better give him another,” the increased current was sufficient tof rom a tiny arc beneath the rim of the head electrode, so that the smell of burned flesh and hair was distressingly perceptible and horrid. It was not long before my nervous system and stomach rebelled and I hurried to the cool outer air and left Sing Sing as soon as I could.”

That was far from the end of the story. In fact it was only the beginning. Hamilton had long favoured poison gas as a better, more humane means of execution. Believing carbon monoxide could be pumped into a prisoner’s cell while they slept, the cell itself being made airtight for the occasion, Hamilton set about transforming his vision into grim reality.

His memoir was published in 1916 when the First World War saw the regular use of poison gases like chlorine, phosgene, mustard gas and cyanide in both attack and defense. Cyanide, though used less often than other chemical weapons, could be devastating to unprotected troops and seemed the most effective and least inhumane option for despatching condemned prisoners.

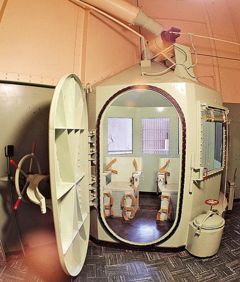

US Army Major Delos Turner also felt gas might be a viable form of execution and with Hamilton and others set about finding a legal jurisdiction prepared to try it. In the early 1920’s the State of Nevada duly obliged. Over the objections of some Nevada legislators, doctors and Warden Dickerson of the Nevada State Prison in Carson City, a former barbershop within the prison grounds was converted into an improvised gas chamber. All that remained was to find a suitable test subject. Chinese gangster Gee Jon, condemned for murdering Tong member Tom Quong Kee during a gang feud, would have the dubious distinction of being the first convict to test the new method.

The executions of Rimieri and Koenig had opened yet another chapter in America’s search for the ultimate wy to inflict the ultimate penalty. Jon was slated to die at 9am on 8 February 1924, almost nineteen years to the day since Rimieri and Koenig had reinvigorated Hamilton’s fondness for lethal gas. As dawn broke on that February morning in Carson City the dawn of America’s gas chambers broke with it.

So too did the improvised chamber itself, almost. Although Jon died quickly (unlike the first electrocution, the best said for that being that William Kemmler actually died at all) witnesses did have to be hurried away after the smell of cyanide gas was noticed outside a supposedly-airtight chamber. That said, Nevada’s gas chamber had been quicker, cleaner and generally better than New York’s electric chair, at least on its first outing. It did not keep its early reputation for long.

Mixing sodium cyanide with dilute sulphuric acid in an airtight room under controlled conditions was as much a learning process as any other method. Just as the electric chair had needed a large number of experimental (often gruesomely-botched) outings to establish exactly how to use it the gas chamber proved no different. It was the most complicated, expensive method America has ever used, it was messy and unlike any other method it could easily kill witnesses and execution teams if not properly used, maintained and repaired.

Mistakes were also common even decades after its introduction. Mississippi replaced its travelling electric chair with a permanent gas chamber in the 1950’s, horribly botching its frist on murderer Gerald Gallego in 1954. In 1983 Mississippi botched the gassing of Jimmy Lee Gray with nightmarish results. It was suggested that in both executions that executioner Thomas Berry Bruce might have been drunk while doing his job.

In San Quentin’s two-seat chamber also saw botch after botch, perhaps the worst being the execution of Leanderess Riley in 1953. Riley, an abnornally small man, managed to escape the estraining straps three times before he could be pinioned long enough for executioner Max Brice to pull the lever.

In 1940 ‘Vampire Killer’ Rodney Grieg had provided yet another horrific memory for San Quentin staff. Strapped into one the chamber’s two perforated steel chairs Grieg, facing away from the witnesses and the fumes rising up around him, cocked his head over one shoulder and flashed them a wolfish grin before starting laugh maniacally at them. His laughter was stilled permanently only moments later.

None of these nightmares (or dozens of others) persuaded Nevada to change its method until the 1970’s when Jesse Bishop became the state’s last ‘gassee.’After its premiere in Nevada the States of Missouri, California, Oregon, New Mexico, North Carolina, Mississippi, Colorado, Maryland, Arizona and Wyoming adopted it.

Just as electrocution brought new words and phrases into the English lnaguage so to did the gas chamber. ‘Electrocution’ was a portmanteau word designed specifically to describe ‘electrical execution’ as it was originally known. ‘Old Sparky’ has starred in many a book, film, song and documentary.

The chamber too has had its share of nicknames. Colorado’s (installed under the rule of Warden Roy Best) became known as ‘Roy’s Penthouse. California’s was known variously as the ‘little green room,’ the ‘coughing box,’ the ‘smokehouse’, the ‘time machine’ and, most famously, a nickname given to it by Warden Clinton Duffy. Duffy, ironically a firm opponent of the capital punishment, gave it a name that writer Raymond Chandler and director Howard Hawks made familiar to readers, movie-goers crime buffs everywhere, the ‘Big Sleep.’

Perhaps fittingly the most recent and probably last use of lethal gas, Arizona’s execution of Walter LaGrand on 3 March 1999, was also a drawn-out affair. LaGrand, who died in Arizona’s gas chamber a week after his brother Karl had received a lethal injection, took eighteen minutes to die. That LaGrand was also a German national gave his case an historical resonance uncomfortable to anybody.

All told, the results of Hamilton’s ‘lethal chamber’ (and the electrocutions of Rimieri and Koenig) were probably far from what he had in mind.

Incidentally, the story of California adopting the gas chamber can be found in my book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in Northern California‘ due out on August 28. It can be pre-ordered now.

Leave a Reply