Your cart is currently empty!

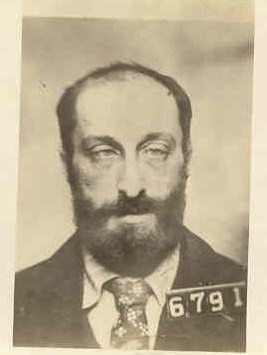

On This Day in 1913 – Jacob Oppenheimer, California’s ‘Human Tiger.’

“The sooner I can cash in my chips the better, as it will save me a lot of trouble and unhappiness.” Jacob Oppenheimer after receiving his death sentence. Caged tigers are solitary, predatory creatures. Constantly pacing their cages, they can inflict violence, disfigurement and death in a split second without as much as a second’s…

“The sooner I can cash in my chips the better, as it will save me a lot of trouble and unhappiness.”

Jacob Oppenheimer after receiving his death sentence.

Caged tigers are solitary, predatory creatures. Constantly pacing their cages, they can inflict violence, disfigurement and death in a split second without as much as a second’s remorse. They can’t feel guilt or remorse, it’s just not in their nature. It wasn’t in Oppenheimer’s nature, either.

Spending a total of eighteen years behind bars, Oppenheimer spent around sixteen of those years in solitary confinement. Deprived of decent food, fresh air, exercise and even light (he was confined in darkened cells with solid doors) the only thing darker than his cell was Oppenheimer’s mind. In almost every sense he was truly a creature of the night.

Even by the standards of Folsom Prison, as grim a prison as America has ever had, its resident predator showed no guilt whatsoever for his laundry list of violent crimes. His response to a death sentence showed no regard for human life, including his own. If anything Oppenheimer seemed to accept his own death as willingly as he inflicted it on others.

From his first robbery in 1892 until he mounted Folsom’s gallows in 1913 Oppenheimer’s life was an epic saga of violence, rebellion and murder. His crimes were so serious the State of California even changed its Penal Code specifically to deal with prisoners like him. Just as Oppenheimer seems to have declared a one-man war on society’s laws and institutions, the State decided he and his kind should be legally eliminated.

The Human Tiger struck so often and so viciously that the California Legislature added an extra paragraph to its Penal Code. Section 4500 allowed for the execution of any life-term prisoner convicted of assault if they intended to inflict serious injury. Because of Oppenheimer the victim didn’t have to die, but their attacker could. Oppenheimer was one of those who did.

Folsom’s gallows claimed ninety-three convicts between the first in 1895 and last in 1937. Aside from Robert Harmon in 1960 Oppenheimer remains the only one to die for assault and one of very few California convicts to be condemned for it. It was a rule used very sparingly, only a few inmates went to San Quentin’s ‘Condemned Row’ as a result. Some of them died for assaults that would have otherwise earned only an extra few years.

The rule outlived Oppenheimer himself, but that so harsh a measure existed at all was down to the Human Tiger. It would have been extremely unhealthy to call him that, though. Just as nobody called Al Capone ‘Scarface’ or addressed Benny Siegel as ‘Bugsy,’ nobody risked their life calling Jacob Oppenheimer the ‘Human Tiger.’ Oppenheimer killed over far less.

His first known offence was, fittingly, a serious crime of violence. Since 1889 Oppenheimer had been working as a messenger boy for San Francisco’s American District Company. The company itself regularly sent him delivering cash and telegrams to brothels and opium dens, but their doing so cut little ice when Oppenheimer began patronizing both on a regular basis. He later blamed his crimes on repeated exposure to such places at so tender an age.

The last straw was when a female cashier (also the manager’s sister) accused him of making crude remarks about her. Oppenheimer denied doing so, claimed another employee had made them and refused to apologise for remarks he’d already denied making. Manager Frank Wehe promptly fired him and, finding deductions made from his final paycheck, Oppenheimer sought revenge. Attempted murder wasn’t a revenge the courts approved of. Oppenheimer drew eighteen months in the House of Correction as a result. If a short, sharp shock was intended to curb his aggression it failed completely. He was just getting started.

1 May 1892 saw another entry in Oppenheimer’s burgeoning criminal record. The armed robbery of a telegraph office saw clerk John Monahan threatened with pistols and instant death if he didn’t immediately open the safe. The safe was opened, its contents taken and Oppenheimer and his accomplice fled the area. Monahan, though severely shaken, was otherwise unhurt. Appropriately for a man like Oppenheimer his accomplice was named Lawless. The telegraph office was on a San Francisco street with an equally ironic name, Sutter and Leavenworth.

Oppenheimer might have fled the scene of the crime, but not the area. 11 June 1895 saw the crime that first sent Oppenheimer to a maximum-security prison. John McIntosh kept a saloon on McAllister and Leavenworth and wasn’t expecting Oppenheimer and his accomplices, two brothers named Walter and Charles Ross. The trio didn’t take a huge haul, but Charles Ross did earn himself fifteen years in San Quentin. He was the only one convicted.

It wasn’t long before brother Walter joined him in California’s penal system. In September 1895 Walter’s sometime girlfriend had threatened to leave him and he took the threat very badly. He choked her unconscious, almost killing her in the process. Not satisfied with that he then stole her bag, jewelry and $150 in cash. Quickly caught, Walter drew twenty-five years, but not in San Quentin. He was sent to the dreaded Folsom, a prison so brutal and miserable convicts once called it ‘the end of the world.’ Jacob Oppenheimer would soon be joining him and the two were on very bad terms. Just how bad Oppenheimer would soon make lethally clear.

Oppenheimer arrived at Folsom in August 1895 to serve fifty years for a violent robbery committed in Oakland in May of that year. Together with his accomplice Berry Harland (serving life for the same robbery) the pair had only one thing in their future, hard time and lots of it. Folsom had opened in 1880, possessing what was then the largest single cellblock of any prison in the nation. Another Folsom first was being the only prison the country to have its own electricity supply.

By 1895 it had also developed a dreadful reputation for violence, cruelty, bloodshed and death. Its numerous executions had already been augmented by numerous murders, violent escape attempts and inmates shot while trying to break out. Discipline was brutal even by the standards of the time. Few Californians really knew just how harsh it really was, even fewer cared. The attitude of many was that criminals deserved whatever they got.

The diet was revolting. Inmates routinely ate beans from metal plates nailed to the tables with buckets of water infrequently thrown over them. The cells were tiny and cramped, only four feet by eight, with little access to fresh air and solid doors with a small flap for observation purposes. In winter they were damp and cold. In summer even ordinary cells became sweatboxes.

Discipline was brutal. Corporal punishment remained in California prisons into the 1940’s. Clubs and rubber hoses were the weapons of choice. Use of the actual sweatboxes, even tinier cells in which inmates could barely breathe let alone move, was standard. More refined forms of brutality involved stringing up prisoners by their thumbs or shackling their arms behind their back and pulling their arms up on a chain so their feet barely touched the floor. They were often left in this excruciating position for some time. The luckier ones were only left dangling. Those less fortunate might be beaten while dangling defenseless.

Most unpleasant of all, especially unruly prisoners would be confined in tight straitjackets and force-fed large amounts of laxatives. Now unable to control their bodily functions, they would be left in dark cells to spend days, week or even months lying in their own filth.

Ordinary solitary confinement was almost as bad. Cramped, cold and damp, the solitary cells resembled refrigerators in winter and ovens in summer. Left without blankets, beds and chairs, solitary cells were also lacking much fresh air. Worst of all were the solid steel doors that blocked out virtually all light. With no artificial light inmates could serve their entire time in solitary in near-total darkness.

Federal law later mandated a maximum of nineteen consecutive days in solitary and Warden James Johnston (later first Warden of Alcatraz) did a great deal to drag Folsom out of the Dark Ages, but neither had reached Folsom when Oppenheimer arrived. Johnston didn’t take over until June 1912, remaining until he took over San Quentin in 1913.

Given the conditions and regime at Folsom then it’s entirely understandable that they’d want to be somewhere else. Oppenheimer, knowing he was in the same prison as Walter Ross, was looking for another form of release; Revenge.

Oppenheimer believed the Ross brothers had betrayed him. That may or may not explain Oppenheimer’s fifty years and Charles Ross’s comparatively lenient fifteen. Whether or not they actually had betrayed him made no difference to Oppenheimer. Never sated for long, the Human Tiger went hunting.

There are no secrets in prison including Oppenheimer’s open hatred of Walter Ross. Today Folsom’s officers would be well aware of feuds among their inmates and one of them would probably have been transferred elsewhere. That didn’t apply in 1898. Confined in the same prison it was only a matter of time before the two ran into each other. On 30 September the Human Tiger finally cornered his prey while waiting to enter the dining room. Walter Ross didn’t get to eat his last meal.

As the inmates lined up outside the dining room door Oppenheimer produced an improvised dagger known to inmates as a ‘shank’ or ‘shiv.’ Fashioned out of a metal file probably stolen from the prison’s workshops, Oppenheimer lunged at Ross, wrapped one arm tight around his neck and stabbed him repeatedly. Ross, mortally wounded, died within an hour of the attack. Prison authorities regarded murder committed within their prison as seriously as on the outside. Already serving fifty years it looked as though Folsom’s gallows would claim another victim.

Eventually it would, but not yet and not for the murder of Walter Ross. Convicted, Oppenheimer was lucky enough to draw a life sentence instead of the noose. He was transferred to San Quentin to serve it on top of the remainder of his fifty years for robbery. Just as one judge had thought eighteen months would curb Oppenheimer’s baser instincts another thought an additional life sentence might work. Neither was right and more men would die as a result. In April Moore’s excellent ‘Folsom’s 93: The Lives and Crimes of Folsom’s Executed Men’ Warden Johnston is quoted on Oppenheimer’s aptitude for aggression:

“He made many murderous attacks on prison officers and fellow inmates. His killings and assaults terrorized. His keepers were puzzled he had demonstrated uncanny ability to improvise weapons and get at his victims despite confinement, surveillance and restraint.”

Transferred to San Quentin, it didn’t take long for the Human Tiger to bite again, this time attacking one of his keepers. On 15 May 1899 Oppenheimer was working in San Quentin’s Jute Mill, by far the work most hated by the prison’s inmates. Opened in 1882 as a means to offset the cost of running the prison it produced thousands of sacks every year. In its first year alone the mill’s products alone recouped half the prison’s annual costs. It burned to the ground in 1909 and convict S.J. Frowman died fighting the fire.

Working in the jute mill was a frequent cause of illness among inmates and so being there was unlikely to put a convict like Oppenheimer in anything other than a foul, antisocial mood to begin with. When, on 15 May, Guard James McDonald reported him to the mill’s chief W.D. Leahy for breaking prison rules that didn’t improve matters. When McDonald reported him again the very next day, Oppenheimer reacted in his usual fashion.

McDonald’s mistake may have been grabbing Oppenheimer by the arm, intending to physically haul him in front of Leahy. Oppenheimer may have seen McDonald’s rousting him twice in two days as the beginning of a personal vendetta and being manhandled only provoked him further. By the time other officers had dragged Oppenheimer off him McDonald had suffered seven stab wounds from another of Oppenheimer’s improvised knives.

McDonald almost died from his injuries. Already serving life plus fifty years there was nothing San Quentin’s authorities could do but throw Oppenheimer into solitary. In time he also received another life sentence. Oppenheimer didn’t seem to care what he’d done to McDonald, but there were influential people who were and they came up with a solution tailored specifically for Jacob Oppenheimer; Section 4500 of the California Penal Code.

Oppenheimer’s name and infamy had spread beyond California’s penal system and as far as its legislators. His record of violent crime and murder, they felt, made it only a matter of time before he killed again. Believing they should be prepared for when, not if, he killed another inmate or prison officer, they did something few legislators have ever done, they added a new section to the Penal Code expressly with one inmate in mind.

Section 4500 is still on the books today and, while very seldom used, has also barely been reformed. It wasn’t even amended until 1959. Its terms were and remain very simple. According to today’s rule any life-term prisoner who uses a lethal weapon to commit a premeditated assault with intent to cause serious injury can receive either life imprisonment or a death sentence. If their victim doesn’t die within one year and one day of the assault they can still face life without parole or life with a minimum nine years before being eligible for parole.

In Oppenheimer’s time Section 4500 was worded rather more simply. Any inmate committing assault with the intention of causing serious injury could face only one punishment; Death by hanging.

For the attempted murder of James McDonald solitary was made particularly unpleasant for Oppenheimer. Just as convicts have a ‘them and us’ attitude to prison officers, officers have the same approach to convicts. Especially convicts who try to murder them. Oppenheimer responded in kind.

On one occasion he set fire to his mattress, later admitting he’d hoped the solitary cells would be unlocked so he could murder a guard. In 1903 Oppenheimer somehow secured some black pepper, probably smuggled from the nearby prison kitchen. A guard noticed Oppenheimer’s contraband when it was thrown into his eyes. Somehow Oppenheimer also obtained a file only to be caught trying to cut through the metal roof of his cell. He attacked another guard, having to be violently subdued while trying to strangle him.

Oppenheimer was kept in San Quentin’s strictest solitary confinement. His books, magazines, mattress and bedding were confiscated and he was frequently chained to the wall of his dark cell. He found himself regularly placed in a straitjacket (for 110 hours on one occasion), hung up by his wrists and deliberately exposed to quicklime fumes that burned his eyes and lungs, causing intense pain. He received clean clothes once every three weeks, only two meals a day, only thirty minutes daily exercise (indoors only) and his cell was kept permanently cold, only a few degrees above freezing.

San Quentin’s staff had done their best to create Oppenheimer his own private hell. As far as they were concerned he could stay there. Courtesy of cleverness, patience and a sack needle probably pilfered from the jute mill, he didn’t. Oppenheimer spent months enduring solitary, grinding the needle until it became a usable saw. This done, he used it to cut six bars. Each bar being one-half inch wide and a half-inch thick and with guards keeping him under close watch, this took enormous patience, skill and guile.

Fellow inmate Jack O’Neil was also in solitary during Oppenheimer’s stay. Oppenheimer believed it was O’Neil who tipped off guards that Oppenheimer was up to something without knowing exactly what. Without warning Oppenheimer found himself repeatedly moved from cell to cell in solitary. Had guards discovered the damaged bars then Oppenheimer wouldn’t have found himself back in his original cell long enough to finish cutting them. They didn’t find the damaged bars and Oppenheimer had time to finish his handiwork. He also nursed an overwhelming desire to finish Jack O’Neil as well.

On 14 August 1907 the Human Tiger was ready to pounce. Guard Manuel Silviera had stepped away from the cell door to wash his hands when Oppenheimer struck. Kicking the cut bars aside he dashed past Silviera headed for the prison kitchen. When he encountered inmate George Wilson, busily cutting bread at the time, Oppenheimer grabbed Wilson’s knife and stabbed him twice before being overpowered by guards. Wilson survived the attack. Oppenheimer wouldn’t survive much longer. Section 4500 was about to claim its first victim.

Oppenheimer hadn’t murdered anyone but under the terms of Section 4500 he didn’t have to. Wilson had been stabbed in the arm and hand, probably while trying to fend off Oppenheimer. Not only had Oppenheimer committed assault with intent to cause serious injury on Wilson, he’d admitted doing so in order to murder Jack O’Neil. With Oppenheimer’s record and Section 4500 having been tailored specifically for him it was an open-and-shut case.

Oppenheimer having no funds meant he represented himself in court, not that it would have made any difference. California’s authorities were intent on seeing him hang and had every reason to do so. Quickly convicted and condemned in October 1907, Oppenheimer showed as much disregard for his own life as he had for anyone else’s. Asked if he had anything to say for the court record before sentencing he responded simply:

“The sooner I can cash in my chips the better, as it will save me a lot of trouble and unhappiness.”

The State of California was in full agreement and so were the California courts. Enter lawyer Gus Ringolsky. Keen and prepared to work for free, Ringolsky worked hard to save Oppenheimer, but to no avail. The State of California wanted Oppenheimer dead. Heard in January 1909, his appeal was quickly denied.

Ringolsky’s second appeal would very likely have failed as well. His own client certainly ensured that in characteristically violent fashion. Returned to Folsom’s Condemned Row to await the gallows Oppenheimer found yet another human being he felt like killing. This time condemned inmate Francisco Quijada was to feel the Tiger’s bite and on Condemned Row itself.

Quijada and another condemned inmate had been using Oppenheimer’s personally-devised ‘tap code,’ similar to Morse code, to devise an escape from Condemned Row. Their plan was discovered and Quijada made two fatal mistakes. First he blamed Oppenheimer for the plot’s failure and then Quijada attacked him. Oppenheimer promptly stabbed him through the heart with a length of sharpened wire. The escape plan had failed, Oppenheimer’s new appeal was now doomed and with it the Human Tiger.

His appeal was heard and quickly denied. California State Governor Hiram Johnson declined to intervene in June 1913 and Oppenheimer was scheduled to hang on 12 July. The State of California had been hunting the Human Tiger for a long time and the hunt was almost over. The only thing between Jacob Oppenheimer and Folsom’s gallows was time and time was rapidly running out.

Ironically the Warden at the time was James Johnston. Johnston was Warden between June 1912 and November 1913. Hand-picked by Governor Johnson to drag Folsom kicking and screaming into the 20th century, he did so well that he went straight to San Quentin and was Warden there until 1924. In 1934 he took the Warden’s job at a third prison, Alcatraz.

Johnston is credited with having done more than any other Warden to improve conditions and eradicate brutality at Folsom. He banned corporal punishment, the use of the straitjacket-and-laxatives, prisoners being hung in chains by their wrists or thumbs and being hung up with their arms behind their backs. Food was improved and officers were disciplined and told firmly that the old ways were gone. In response many quit or were fired. One punishment Johnston couldn’t remove was the gallows and Oppenheimer was doomed to face it.

Oppenheimer remained true to his word to the bitter end. He’d told the sentencing judge that death would solve all his problems and perhaps it did. He would have been thoroughly familiar with the peculiar ritual of Condemned Row. The death cells were within feet of the gallows itself and inmates awaiting execution could hear their predecessors drop to their deaths on the gallows at the end of the tier.

New York’s second death house at Sing Sing had been custom-built precisely to avoid inmates hearing the final moments of their fellow-condemned. They’d discovered what with hindsight seems blindingly obvious, that it often drove condemned inmates mad. Oppenheimer wasn’t even bothered. The twenty-eighth man to hang at Folsom, he spent his final night smoking cigars and enjoying good food sent to him by well-wishers. He also had a farewell concert. Until 9pm on his last night he listened to music, particularly the works of John Phillip Sousa. At 9pm ‘Taps’ was played, the last tune he would ever hear. With that h simply put a handkerchief over his face and fell asleep.

Oppenheimer declined a final breakfast but not from fear. He’d just overindulged on the cigars and treats the night before. Still showing a sullen indifference to his fate he was dressed in a suit supplied by the prison. It was the same suit worn by other condemned men only washed, pressed and kept for the next man to wear. When his time came at dawn on 12 July 1913 he walked his last mile, actually only a few steps between his cell and the gallows. Asked by prison staff if he had any final words, Oppenheimer remained as indifferent as ever. Society was through with him and he with it. According to ‘Folsom’s 93’ he also made a brief speech expressing his opposition to capital punishment:

“Calmly leaving myself of out the question, I want to say that capital punishment is a relic of the barbaric age. It ought not be tolerated. I hope that in every country the time will soon come when it will be abolished . . . I will not be the last to go before this practice is abolished but I will be a martyr to the cause.”

According to witnesses he finished his speech by suggesting the gallows had no deterrent effect, at least not for him personally:

“You know, this is no punishment for me. This is nothin’. I have suffered a thousand deaths in the prisons. This is just nothin’.”

The signal was given and the trapdoor dropped. The Human Tiger would prowl no longer

His story didn’t end there. Section 4500, albeit modified, remains in California’s Penal Code. Oppenheimer, for whom it was personally intended, was the third prisoner condemned under its provision. Other inmates like Robert Wells and Robert Harmon were sentenced. Harmon went to San Quentin’s gas chamber on 9 August 1960. Wells was reprieved.

Many might think Jacob Oppenheimer was a brute, an unthinking thug capable of only murder and mayhem. He wasn’t, he was also an intelligent thinker, ingenious and sometimes thoughtful and reflective. The Human Tiger had a brain as well as teeth and claws. Decades before Carl Panzram, Caryl Chessman and Mumia Abu-Jamal, Oppenheimer was also a writer and poet of some talent. His essays, books and poetry are interesting reading.

Today Jacob Oppenheimer is often forgotten and overlooked. Had he been in prison today he would have been handled very differently, though never without the highest security precautions. He was cunning, violent, homicidal and extremely dangerous man, but also might have had something more to offer. When he dropped through Folsom’s gallows it only served to prove one thing;

Both he and the State of California could now rest in peace.

The story of the Human Tiger and his keepers can be found in my forthcoming book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in Northern California,’ published on August 28 2020. My previous book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York‘ is currently available.

All donations gratefully received.

Running a site costs money, it’s as simple as that. Writers also exist on coffee as much as anything else. If you like what I do then just throw me the odd cappucino now and then. Thanks

$3.00

Leave a Reply