Your cart is currently empty!

On This Day in 1851 – Josefa ‘Juanita’ Segovia, rough justice or legal lynching?

Present-day California is often seen as the most liberal, tolerant state in the Union. It‘s sold with images of sunshine, surfing, and hippies; a relaxed, easy-going kind of place where, within reason, anything goes. This is a fallacy. While 1967 might have been California’s ‘Summer of Love’ July of 1851 wasn’t. Certainly not for…

Present-day California is often seen as the most liberal, tolerant state in the Union. It‘s sold with images of sunshine, surfing, and hippies; a relaxed, easy-going kind of place where, within reason, anything goes. This is a fallacy. While 1967 might have been California’s ‘Summer of Love’ July of 1851 wasn’t. Certainly not for a Mexican lady known as ‘Juanita’ and certainly not from the population of Downieville, then a mining camp. She was the first woman to hang since California achieved Statehood, one of only four women executed in the state since 1850.

Her story is one of intolerance, injustice, sexism, ignorance and outright bigotry. That said, a modern trial might well have convicted her of murder based on the evidence given. She admitted stabbing Frederick Cannon, and declared openly that she’d do the same again under similar circumstances. As much as her trial might seem like a travesty and her punishment swift and brutal her own testimony wasn’t likely to inspire sympathy or clemency.

Known variously as ‘Juanita,’ ‘Josefa Segovia’ and ‘Josefa Loaiza’ she was to end her days at the end of a rope accused of murder, the first woman to hang in what had only recently become the State of California. Today’s Golden State was anything but golden for Mexicans at the time. Early statehood remains a particularly uncomfortable period in California’s history.

To give her story context it’s necessary to consider the attitudes and circumstances of the era which are very different from today. Doubtless many present-day Californians would look at the behavior of their forefathers and be appalled by it, especially the free use of ‘miner’s law’ in place of the rule of law as we now know it. The standards of today can’t be applied to California as it was in 1850.

The Mexican War began in 1846, ending in defeat for Mexico and the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. For many Mexicans the treaty’s terms had added insult to injury. A huge swathe of what had been Mexican territory. Some 525000 square miles became part of the United States overnight. This included part or all of present-day California, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming.

The treaty also resolved the issue of the border between Mexico and the US. In addition to giving up all claims to Texas (formerly northern Mexico) the Rio Grande became the border between the two recently-warring nations. It was a huge blow to Mexican pride and prestige. Worse was to follow for the Mexican population of the region

It would be fair to say that Mexicans were regarded as lesser beings by many whites or ‘Anglos’ as they were often known. At best, many regarded Mexicans as second-class citizens. At worst they were regarded as a lower form of life altogether. Josefa Segovia was one of many who suffered as a result

Following the treaty, life for Mexicans was changed completely. They lost any status, property, titles and political power, even their nationality changed almost overnight. Regardless of what they had been before California became part of the US they were seen as nothing after it. Even the culture and traditions they’d grown up with were seen by many Anglos as worthless and of no value.

Attitudes only worsened with the start of the Gold Rush in 1849. When gold was first found near Sutter’s Mill only locals knew of it. Only around 5000 prospectors, mostly locals with some Americans and foreigners, were working the goldfields by the end of 1849. A year later fortune-hunters were arriving in their tens of thousands from all over the world. By the end of 1850 there were more than 80000 Anglos in California either prospecting or in gold-related businesses. The inconceivable began to happen; too many prospectors and not enough gold.

With enormous speed the gold rush created a huge melting-pot of different cultures and traditions without creating anything resembling racial harmony. In fact, as competition increased and gold became steadily more scarce, racial disharmony, ill-feeling and outright violence became widespread and then endemic. Some, for political and commercial reasons, stoked the fire.

At first prospectors were highly egalitarian for their time. They were too busy trying to make their own fortunes to be overly prejudiced. Gold was also remarkably thick on the ground, literally. It wasn’t as simple a matter as walking round picking up fat nuggets off the ground, but there was certainly enough for everybody in the early days.

Even those whose dreams hadn’t come true often made their fortunes supplying food, tools, explosives, timber and anything else prospectors wanted. Prospectors became used to vastly inflated prices and vendors took full advantage. If mining didn’t pay off then ‘mining the miners’ still could.

El Dorado County was named after a mythical city of gold for a reason. As the initial deposits were scooped up and prospector numbers increased things became progressively harder. Attitudes began to change toward Mexicans and not for the better.

By the spring of 1850 the miners were often already divided by nationality. Anglos lived and worked with Anglos, Mexicans with Mexicans and so on. Gold was still plentiful but not as much as it had been and the Anglos had already started grumbling. Some, notably a group of several thousand Americans from the Oregon Territory, started posting notices ordering non-Anglos off their claims within twenty-four hours.

Accompanied by a large group of armed men these notices threatened violence, even death, to any non-Anglo who didn’t leave immediately. Driven by racial prejudice and nationalist sentiment these Anglos began forcing those they regarded as foreigners off their claims. American gold, they said, was for Americans especially white ones. Foreigners, even those who’d been born in California, had no right to even be there let alone profit from the gold they sought.

It wasn’t long before the threats of violence became a grim reality. Foreigners (shorthand for non-whites of any persuasion) were routinely driven off their claims by threats and armed mobs. Those who refused to be ejected risked death; some got exactly that. Still some 4000 fortune hunters were arriving in California every month only adding to the tension.

The Anglos didn’t just resort to blatant violence. In the spring of 1850 California’s new Legislature passed the Foreign Miners Tax Act after pressure from the Anglo contingent. Officially named ‘An Act for the better regulation of the Mines and the Government of Foreign Miners’ it imposed a monthly twenty-dollar fee. In theory the tax was meant to penalize all non-Americans wanting to prospect although Native Americans were exempt.

In practice it was applied mostly to non-Anglos. Faced with protests and unrest among whites regardless of their country of origin the act was swiftly rewritten. Native Americans remained exempt and so were anyone deemed a ‘free white person’ (not a slave, in other words) or anyone who could become an American citizen.

It was an expressly racist piece of legislation in both theory and especially in practice. Within one year of the Act passing an estimated 10000 Mexican miners left California entirely. In 1851, the year Josefa Segovia killed Frederick Cannon, it was repealed in favor of a new law charging only three dollars per month. By then, of course, it had already served its purpose.

Officially touted as intended to raise tax dollars for the state, in reality it was another way of driving non-Anglos from their claims. Failure to pay this exorbitant, fraudulently-described fee for the mere chance of hitting pay dirt, however slim that chance might be, could be ruinous to non-payers.

Segovia was seen by Downieville’s Anglos as a typical Mexican woman, probably every stereotype they’d ever seen or heard. In a relationship though possibly unmarried, Segovia was said to be intelligent, pretty, vivacious and hot-tempered. While partner Jose was a gambler working at the Craycroft Saloon and Segovia worked there as a hostess. Some undoubtedly saw her as a woman of loose morals for living unmarried, especially with a gambler.

They might also have readily interpreted her being a hostess at the saloon to mean she was also a prostitute as many hostesses were. She wasn’t unpopular with the locals despite her hot temper and allegedly dubious morals. At least not until Segovia (a Mexican) killed a man named Frederick Cannon who also happened to be white.

Cannon had been celebrating Independence Day with some friends and, much the worse for drink, had behaved boorishly toward Segovia on the evening of 4 July. As people often do when intoxicated, he turned up at Segovia’s adobe house in the dead of night. Stumbling drunkenly through the door Cannon’s friends quickly dragged him away. Opinions differ as to what happened when he came back.

Some said Cannon had returned to make amends. In the manner of penitent drunks everywhere he woke up with a throbbing head and, deeply embarrassed, returned to the Segovia home intending to deliver an apology. Others said he returned still drunk and in a foul temper, kicked open the door and trespassed while shouting insults. Whether he returned to apologize or pick a fight didn’t matter as much as his being fatally stabbed by Segovia.

His second visit was even less welcome than his first. Tempers hadn’t cooled much since he’d been dragged away by his friends and they boiled over completely when he returned. As tempers flared and Cannon was alleged to have grossly insulted her, an enraged Segovia produced a knife. She was as well-known for possessing a knife and for her hot temper. Within minutes she’d fatally stabbed Cannon and fled to Craycroft’s Saloon where she was later found.

She couldn’t have picked a worse hiding place. She was well-known in the town, the Craycroft was her place of work and it also doubled as Yuba County’s Court of Sessions with Judge Rose presiding. Unfortunately for Segovia California’s law enforcement was still largely a work in progress, the rule of law existing in name more than reality. Downieville, for instance, didn’t have an actual courthouse until 1854. The stage was set for what today would be called a legal lynching.

With Cannon dead Segovia faced furious Anglos and a storm of anti-Mexican prejudice. Whether Cannon’s death was murder or manslaughter will probably never be known. He’d certainly behaved badly, but whether he’d ever posed a physical threat to Segovia, a threat that might have justified her killing him, was never defined. What happened to Segovia as a result can never really be justified. Angry and with all their inherent prejudices the local Anglos were reluctant to wait for the formalities of courts and trials. They wanted their own form of justice and lost no time in taking it.

Outside of the bigger cities and towns California’s law and justice were then as makeshift and ramshackle as the mining camps themselves. With little in what we’d nowadays call professional law enforcement the miners often exacted immediate and brutal punishment for even minor crimes. A young boy caught committing petty theft might have his ears cut off, for example. What was then called ‘miners law’ was fast, brutal and standard practice.

In addition to racial and profit-driven prejudice, crime in the goldfields was rampant. Theft, robbery and murder were almost daily occurrences in the rougher parts of the goldfields. In the eyes of many Anglos foreigners were to blame, especially those of Latin-American origin. The most notorious gold rush-era bandit, Joaquin Murieta, was Mexican. Many of the region’s most notorious bandits were also Mexican or, to many Anglos, close enough.

Prejudice against non-Anglos was so fierce that Murieta became as much a hate-figure for Anglos as he was a hero for some Mexicans. Any Mexican committing an act of violence, especially against an Anglo, could expect rough treatment or even death. Josefa Segovia was one of thousands who suffered exactly that.

Where killings were concerned lynch law was often the order of the day, what was then called ‘life for life.’ For a Mexican accused of murdering an Anglo, even a Mexican woman, many Anglos tended to want punishment there and then. Lynching wasn’t confined to foreigners, but was a regular occurrence for malefactors of all kinds. Racial prejudice made non-Anglos the most likely victims of it especially if accused of harming whites. Josefa Segovia was no exception to the rule.

There are numerous conflicting accounts of Josefa Segovia’s crime and punishment. Some regard her as a murderer receiving nothing more or less than the punishment of the day. Others question whether she was a murderer at all, considering that Cannon had made unannounced, unwelcome visits twice in twenty-four hours. Today’s courts would certainly have been more formal and probably more merciful. ‘Miners justice’ was neither.

Her trial, such as it was, was nothing like what would be expected today. By modern standards due process simply didn’t exist in the goldfields. Even policing was often notional. Lawmen were often hard to find, skilled ones even harder and bribe-taking was often a fact of life. It was also the era of the ‘circuit judge.’

With so few judges and courts district judges were still often ‘circuit riders’ with a list of towns in which they presided. They rode from town to town within their district dispensing justice as they went. Even when criminals were arrested and clearly guilty circuit judges might visit a town only once every couple of months, try a long list of cases as quickly as possible and ride on.

Accounts vary of just how quickly miner’s law handled Josefa Segovia. She was tried within hours of the killing by a jury composed largely if not entirely of Cannon’s friends and acquaintances. Another account describes the ‘trial’ as having happened within a couple of hours of the alleged murder. While unthinkable today this was typical of the time. Very few people even attempted to protect or defend her. Against a furious mob, some of whose members were probably armed and perhaps intoxicated, that was understandable.

It was said that local doctor Cyrus Aiken testified that Josefa wasn’t fit to stand trial and may have been pregnant at the time. As a result Aiken was allegedly forced out of the ‘court’ and also out of Downieville entirely. A Nevada lawyer, Mr. Thayer, was also said to have tried to defend her. It was reported that he wanted to protest her execution and wanted a fair trial to decide whether or not a murder had actually been committed.

Thayer’s treatment was said to have been no better than Aiken’s. He was allegedly beaten and thrown out of the ‘trial’ for wanting to confirm whether a murder had actually been committed. The locals seem to have already decided that one had and were going to punish the murderer regardless. With nobody else willing or able to prevent miner’s justice, Josefa Segovia’s fate was sealed from the start.

Scottish writer J.D. Borthwick spent three years in the California goldfields. He spent his time meeting and getting to know people from all walks of life and his travels included arriving in Downieville a few weeks after Segovia was hanged. Though Borthwick was going by what locals told him (making what he heard less than entirely accurate) his is one of the few accounts of the incident. His memoir ‘Three Years in California 1851-1854’ takes up the story:

‘A Mexican woman one forenoon had, without provocation, stabbed a miner to the heart, killing him on the spot. The news of the murder spread rapidly up and down the river, and a vast concourse of miners immediately began to collect in the town.’

The vast concourse had certainly collected, seemingly having already decided that Josefa Segovia was a murderer.

‘The woman, an hour or two after she committed the murder, was formally tried by a jury of twelve, found guilty, and condemned to be hung that afternoon. The case was so clear that it admitted of no doubt, several men having been witnesses of the whole occurrence; and the woman was hung accordingly, on the bridge in front of the town, in presence of many thousand people.’

Borthwick was certainly going by what he’d been told. He didn’t get her name and nor did he seem overly bothered to check what he’d been told, either. In fact he then defended the practice of lynching:

‘Anyone who lived in the mines of California at that time is bound gratefully to acknowledge that the feeling of security in life and person which he there enjoyed was due in a great measure to the knowledge of the fact that this admirable institution of Lynch law was in full and active operation.’

He also found time, as did many Anglos, to blame Mexicans like Josefa Segovia for much of the crime in the goldfields:

‘Theft or robbery of any considerable amount, however, was a capital crime; and horse-stealing, to which the Mexicans more particularly devoted themselves, was invariably a hanging matter.’

Borthwick’s attitudes were typical of many Anglos in the goldfields. There was a choice between rough justice or no justice given the inefficiency of the legal system in gold rush-era California. Lynch law or no law was the order of the day and, given that Mexicans were seen as responsible for much of the crime they also took much of the punishment.

Many people also believed they had a choice between rough justice or none at all. California had only formally entered the Union in September 1850. Less than a year had passed since statehood and the state’s legal system, along with every other branch of government, still barely existed in any meaningful form outside of cities. The goldfields in particular had only notional official law enforcement so law was enforced by those who lived there unofficially and ruthlessly. As Borthwick put it:

‘Society had to protect itself the most practical and unsophisticated system of retributive justice, quick in its action, and whose operation, being totally divested of all mystery and unnecessary ceremony, was perfectly comprehensible to the meanest understanding.’

What Borthwick defended as the ‘admirable institution of Lynch law’ wasn’t the exception in California’s goldfields at the time, it was the rule. While many people might have been grateful for some law rather than no law, Segovia probably wasn’t one of them. She had been treated with little resembling either law or formal justice as we would know it.

Opinion wasn’t as uniform outside Downieville as in the camp itself. The Sacramento Time and Transcript was unequivocal in condemning the event:

‘The act for which the victims suffered was entirely justifiable under the provocation. She had stabbed a man who persisted in making a disturbance in her house and had greatly outraged her rights. The violent proceedings of an indignant and excited mob, led on by the enemies of the unfortunate woman, were a blot upon the history of the state. Had she committed a crime of really heinous character, a real American would have revolted at such a course as was pursued toward this friendless and unprotected foreigner.’

The treatment of Josefa Segovia, brutal though it was, was all too typical of the time. With a huge swathe of territory and resources only recently taken from Mexico many Anglos wanted to make their dominance absolutely clear. Racial prejudice also played a large part in Mexicans being singled out for mistreatment and harsh punishment. According to Margo Gutierrez and Matt Meier’s ‘Encyclopedia of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement’ many lynchings resulted from allegations (accurate or otherwise) of Mexicans stealing horses and livestock or raping, robbing and killing Anglos.

According to scholars William Carrigan and Clive Webb in ‘The Lynching of Persons of Mexican Origin or Descent in the United States 1848 To 1928’ lynchings of Mexicans were out of all proportion to their numbers. Between 1850 and 1895 Mexicans accounted for over one-third of American lynchings despite representing only fifteen percent of the population.

Gordon Young’s ‘Days of ‘49’ references Segovia’s crime, trial and punishment. In the absence of an actual courtroom Young describes her trial taking place outdoors. According to Young she was:

‘Put on a pavilion in the center of the town and twelve men responded eagerly to the call for a jury.’

Lynching might have been the nearest some areas got to law and order at times, but it was also a way to intimidate and repress minority groups and consolidate power in troubled areas like 1850’s California. It didn’t seem to intimidate Segovia herself. The outcome of her trial was probably a foregone conclusion, especially when she told the court:

“I told the deceased that was no place to call me bad names come in and call me so and as he was coming in I stabbed him.”

Hardly the sort of evidence to inspire sympathy, especially when on trial for murder. It also raised a question about her self-admitted motive. Exactly who provoked who into coming within arm’s reach of a knife and did Cannon even know she was armed? Had he known she was in possession of a knife would he have been so foolish as to escalate things even further even while still intoxicated? Not that the jury needed much help deciding her case. She was caught, tried, convicted, condemned and executed in a single day. Jose was acquitted, but ordered to leave Downieville immediately.

Whatever she said to her accusers Segovia was most likely doomed and knew it. She had undeniably done the deed, she behaved defiantly toward the court (such as it was) and was a Mexican woman who had clearly killed an Anglo man. Saying she’d do the same again in similar circumstances would have probably lost her the case in a modern court. In an area run using lynch law she effectively passed her own death sentence.

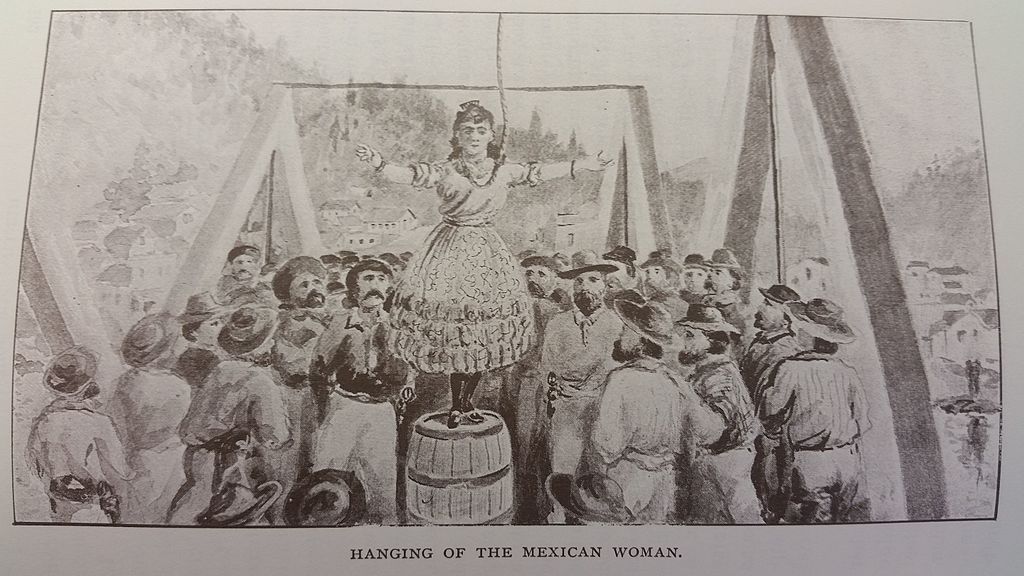

That sentence was swiftly delivered. It wasn’t a long walk to the Jersey Bridge spanning the Yuba River, nor was it hard to install a wooden platform for her to step off once her noose had been tied. She showed considerable courage and bravado on the way. She was reported to have tossed her hat to the spectators while on her final walk and to have stood firmly on her makeshift gallows. With the rope secured to the bridge and around her neck all that remained was for her to step or be pushed off. To use a phrase common at the time she was about to be ‘launched into Eternity.’

Segovia maintained her defiance right to the bitter end. With perhaps several thousand in attendance (which would have been most of Downieville’s population at the time) she wasn’t about to disappoint her audience. Complaining at her arms being tied she co-operated when the hood and noose were fitted. Her final request was that she be given a proper burial.

As she stepped off the simple wooden platform some claimed she even shouted her final words to the large crowd;

“Adios Senores.” (“Goodbye, Sirs.”)

Were her last words defiance, acceptance or a sneer directed at those who tried and hanged her so quickly? Did she feel any remorse for the killing she had so recently committed? Was it murder, manslaughter or self-defense? We’ll never really know now. The only person who did hung lifeless from the Jersey Bridge.

Her case can be found in my forthcoming book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in Northern California, available for pre-order now and on sale from August 28.

One response to “On This Day in 1851 – Josefa ‘Juanita’ Segovia, rough justice or legal lynching?”

-

A little less political correctness please

Leave a Reply