Your cart is currently empty!

San Quentin, Doil Miller and Alfred Dusseldorf – Justice? Or just law?

At San Quentin 7 March 1952 dawned grey and cold, not unusual for the area. The prison’s inmates, then nearly two thousand strong, knew that day was unusual. Two of their number, Miller and Dusseldorf, were to die at 10am that morning for a robbery and murder committed in Alameda in 1949. As they sat…

At San Quentin 7 March 1952 dawned grey and cold, not unusual for the area. The prison’s inmates, then nearly two thousand strong, knew that day was unusual. Two of their number, Miller and Dusseldorf, were to die at 10am that morning for a robbery and murder committed in Alameda in 1949.

As they sat in the twin cells nicknamed the ‘ready room’ they pondered their imminent fate. Dusseldorf, a career felon with multiple convictions, had an appeal being considered. He at least had some small shred of hope though, this late on, it was a very small shred indeed, but a shred nonetheless. Miller, with prior record before his arrival on Condemned Row, had none other than the Governor deciding to grant clemency. He too had hope, equally small at best, but still hope. At least until the arrival of Warden Harley Teets, anyway.

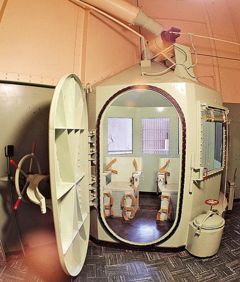

Teets, a fair Warden known for his compassionate attitude to the condemned, had had a long night overseeing the preparations for the morning’s execution. When the clock ran out he would supervise the execution itself, a task he almost invariably hated and never looked forward to. What convicts and staff alike called a ‘double event’ meant both the gas chamber’s perforated steel chairs would be prepared. Unless either the Governor or the courts intervened both chairs would be occupied.

It was cheaper to gas two prisoners at the same time and simpler to ready the chamber once instead of twice. Just as Britain’s hangmen could and often did drop two prisoners at once San Quentin’s chamber was a two-seater. In the 1950’s convicts condemned for the crime they committed together frequently died together as well. It made everything easier for all concerned except perhaps the prisoners themselves.

If Teets had though the night before had been difficult the morning after had just become infinitely worse. Veteran convict Dusseldorf knew that once his one mandatory appeal had been denied he either had to hire a lawyer or file his own appeals from his cell. Miller, with no prior criminal history, was a far better candidate for clemency but knew very little about the appeals process once his mandatory appeal had been denied.

By a bitter irony the veteran felon, aided by legendary jailhouse lawyer Caryl Chessman, was far better prepared to avoid the chamber than the previously honest Miller. Teets had just found that out first-hand. He dreaded his next visit to the ready room and for a very simple reason. The ready room’s layout meant that he would have to give good news to one of them and the worst possible news to the other. He would also have to do so within earshot of both men at once.

Teets had just finished a dreadful phone call to the Federal District Court clerk. One of the clerk’s jobs was monitor all death penalty cases nearing their conclusion, informing Wardens around the country whether there were any stays or reprieves issued by Federal courts. Dusseldorf had filed one with the Federal District Court and a stay had been issued. Teets (or so he thought) was making a routine call confirming that neither convict would die that morning. It had just become a very un-routine phone call and Teets had to break the news.

Having waited in his office from 9:15to 9:45 without receiving a call Teets headed for the gas chamber itself. Another line was kept permanently open in the chamber room, saving time (if not always lives) when reprieves or stays arrived at the last minute. Provided the chamber hadn’t been activated already that phone delayed many an execution, often until a commutation or successful appeal. Shortly after Teets arrived and with the ‘double event’ only a few minutes away, it rang. The clerk of the court had called. Alfred Dusseldorf had won a stay of execution.

Teets waited, expecting to hear the same about first-time offender Doil Miller. Nothing was said about him. Hoping he was wrong Teets asked the clerk:

“What about Doil Miller?”

There was nothing. Not having filed an appeal Miller was to die as scheduled. Dusseldorf would be escorted back to Condemned Row on the North Block’s fifth floor. In turn that meant Teets would have to visit Miller and Dusseldorf in the ready room cells and break the news to both of them at the same time. There was no way to deal with them separately. The two cells were simply holding pens, their walls mere rows of bars and the doors likewise.

Teets ordered a delay while the problem was clarified. It was clarified very quickly, very simply and entirely not to his liking. He asked the clerk to check again. Surely career felon Dusseldorf would go and first-timer Miler would be spared if only temporarily. It had to be a mistake. Only it wasn’t.

Dusseldorf and Miller were only a dozen steps from the chamber, Miller sitting silently with his head on his knees. Dusseldorf, still hoping for a last-minute miracle, chatted nervously with the death-watch guards. Neither had especially good chances of either a stay or commutation, but both still had some hope. The tension was as stifling as the gas they both knew was ready and waiting. The chamber room phone rang again, the clerk calling back with confirmation.

“There is nothing before this Court concerning Miller.”

That was it, Dusseldorf had pulled a rabbit out of the hat and Miller had not. Neither did the Governor pick up the phone. He didn’t have to, Teets immediately called the Governor’s office hoping for a reprieve or commutation. There was none. It was almost over, but not before Teets endured what he later called the worst moment of his life. He had to tell the pair that one would live, at least for now. The other was about to die.

Miller was impassive despite the nervous strain and loss of all hope. Teets told him that there was nothing delaying his imminent execution and Miller took it surprisingly well. When Teets told him he had also checked with the governor’s office and no clemency had been granted he remained as outwardly calm as anybody could.

“It’s all right… I guess I should have written one of those letters.”

Dusseldorf was more emotional, at least outwardly. He cried briefly when the stay was announced and he was put in restraints for the short elevator ride back to his cell. Before he left Dussseldorf had little to say to his partner-in-crime. It had all been said already. As he left to go back upstairs he took a long look at Miller before saying simply:

“So long, fella.”

With that Dusseldorf was immediately removed. Miller remained. Everybody involved was as uncomfortable as anyone could be. Whatever their crimes, staff felt, condemned convicts should not have to suffer like this especially not right before dying. It made no sense that Dusseldorf, the veteran felon, should get a stay when first-timer Miller did not. It made even less sense when it Dusseldorf who had fired the shots and Miller had only been the look-out man.

Whether it was sensible or senseless, justice or just the law, it made no difference. Doil Miller was going to die. He did so if not willingly at least quietly. It may have been some relief to him when all was said and done. He was quickly seated, strapped down and the airtight door sealed. All that remained was a silent signal from Warden Teets.

When the signal was given, the lever pulled and cyanide mixed with dilute acid the gas formed steadily, swirling round him in an almost invisible cloud. Much to everybody’s relief (possibly including his own) Miller died relatively quickly. It only took a few minutes for the prison doctor, listening to Miller’s heartbeat on a specially-designed stethoscope, to give a signal of his own. Doil Miller was dead.

By then Alfred Dusseldorf was back in his cell five floors above the chamber where Miller slumped steeping in cyanide gas. If Dusseldorf thought his time would never come he was sorely mistaken. He continued fighting his case with Chessman’s hard-earned experience and advice to guide him, but to no avail. Although he came close to winning Dusseldorf never quite pulled it off. On 9 September 1954 he was escorted back down to the ready room. At 10am the next day he walked into the chamber. He never left alive.

It had all been entirely lawful and legal. Both men had been convicted and condemned. Both men had participated in the crime that sent them there. Both ultimately died for it. But was it justice?

Or just the law?

Leave a Reply