Your cart is currently empty!

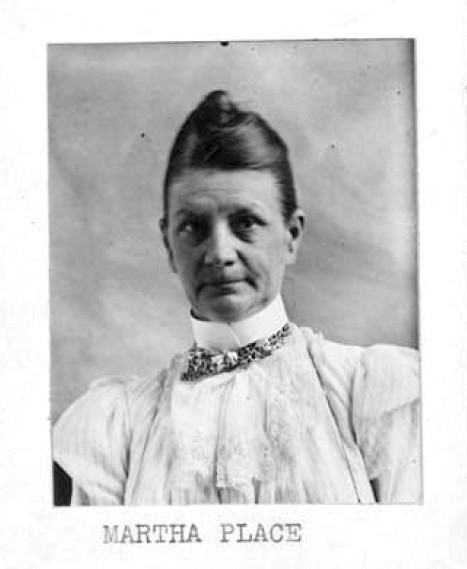

On This Day in 1890 -Martha Place, the first woman in the electric chair.

A free chapter from my book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York,’ available now. Like many countries the US has an at times contradictory attitude to its death penalty, no more so than when a woman faces execution. Women account for fewer than 5% of death sentences in the US and less than 1%…

A free chapter from my book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York,’ available now.

Like many countries the US has an at times contradictory attitude to its death penalty, no more so than when a woman faces execution. Women account for fewer than 5% of death sentences in the US and less than 1% of those executed have been female regardless of their crime. That isn’t to say that female killers are less brutal or cruel than their male counterparts although they are far rarer. They’re also far less likely to die even when a male co-defendant does.

Murderer Martha Place caused particular controversy not only for her gender but also the way she died. In 1890 William Kemmler became the first convict ever electrocuted. In 1899, nine years and forty-four male convicts later, Martha Place became New York’s 46th electrocution and the chair’s first female victim.

Born Martha Garretson in New Jersey in 1849 Martha had been widowed and had a son before meeting Brooklyn insurance adjuster William Place. Her son had been left in the care of his uncle while William, also widowed, lived at 598 Hancock Street with daughter Ida. At first engaged as William’s housekeeper she became his wife within a year of meeting him. There were problems from the beginning.

According to Martha, William’s relatives were hostile almost from the start, refusing to have anything to do with her. William also continually refused to allow her son to live with them. Son Ross had been born to Martha’s first husband, a man named Savacool. An unhappy marriage, he couple had separated after only four years.

Her first husband had apparently headed west and never returned. When he’d left Martha in poverty she’d arranged for Ross’s adoption by wealthy harness manufacturer William Aschenbach in Vallsburg, New Jersey. In memory of their deceased son the Aschenbachs had changed his name from Ross Savacool to William Aschenbach, Junior.

Again according to Martha, Ida was a constant problem. In Martha’s view Ida was sly, antagonistic and disrespectful. She didn’t appreciate anything Martha did and in Ida’s view Martha couldn’t do a thing right. The more Martha tried to bring her to heel the more Ida deliberately defied her. According to Martha William continually indulged Ida’s rebellious behavior.

This wasn’t entirely accurate on Martha’s part, or fair. Ida, being a seventeen-year-old still grieving for her mother, might not have been the easiest stepchild to live with. Martha was also known as a martinet with a vicious temper. Things had to go her way and anyone not toeing her line usually suffered for it. Even her own brother (who ascribed her vile temper to a head injury suffered in her early twenties) admitted she had the worst temper he’d ever seen. Ida (as troubled teens often do) made a point of defying her. While perfectly normal for a teenager, especially a bereaved one, it was a mistake that would cost Ida her life.

By 1898 the Place family had been living on Hancock Street for some years. No longer the housekeeper, Martha employed maid Hilda Jans to help look after the home and on 7 February 1898 it was Hilda who first noticed something wasn’t quite right. An almost-overpowering stench resembling carbolic acid was wafting through the house and Ida was nowhere in sight. William had already headed off to work in Manhattan and wouldn’t return until around 5:30 that evening.

Hilda, finding the smell so severe her eyes were watering, soon found herself being rudely upbraided by Martha for not working faster. There was nothing unusual about that, Martha was well-known for her temper and sharp tongue. According to Jans, Martha initially denied noticing anything unusual before barely acknowledging it:

“Why. Yes. I do notice something, now that you mention it. But it’s hardly carbolic, Hilda. It’s not an acid smell, more likely a gas leak.”

Martha’s manner immediately became cold although her voice remained neutral. Hilda Jans, knowing Martha’s temper, knew better than to press her further. Increasingly frequent domestic disputes between Martha and William were already a common talking point among local gossips, especially the time William hauled his wife before a magistrate for threatening Ida’s life.

Jans didn’t know that at around 8:30 that morning Martha had carried out her threat. Had she continued pressing Martha about the acidic stench Hilda might very well have been Martha’s second murder of the day. Later that day, William Place very nearly was. Before then, though, Hilda found herself given her walking papers.

Out of the blue Martha told Hilda the family was leaving Brooklyn to live in New Jersey. It was at short notice, claimed Martha, and along with a month’s salary in lieu of notice Hilda would receive a bonus provided she and her belongings were out of the house by 5pm that day. The bonus for so quick a departure was, according to Martha, husband William’s idea. It also meant that (aside from the deceased Ida) only William and Martha would be there when he returned home.

Before she left Hilda was given an errand to perform. She was to collect Martha’s bankbook from the Brooklyn Savings Bank and arrange for Martha’s trunk to be sent to New Jersey by train. An express man was to pick it up and deliver it to the station. While out fetching the bankbook Hilda Jans also arranged for her own belongings to be collected. With that she left the house, though not Martha’s story. She would return to deliver especially damaging testimony at Martha’s trial.

Having already murdered her step-daughter Martha had the same in mind for her husband. When William returned home at around 5:30 he let himself in as usual and Martha was lying in wait. William Place didn’t get a warm welcome. Unaware Ida was dead and Hilda no longer there he walked through his own front door. He described it from his hospital bed shortly before detectives told him of Ida’s murder:

“She came rushing down the stairs. I saw too late that she carried an axe. I wanted to escape, to warn my daughter not to enter the house. But as I tried to reach the front door, Martha struck me with the axe. Her eyes were cold with hate. She raised the axe again. After that I only knew agony and a kind of delirium.”

William was critically injured. He didn’t manage to get through the front door into the street, but his cries did alert the neighbors. Norris Weldon and his wife heard screams and what sounded like: “Awful cries and moans. Somebody was screaming ‘Murder!’ My wife and sister heard it too.”

Fearing something dreadful had happened and knowing Martha’s temper Norris Weldon was first to summon assistance. Rushing out of his home he went in search of the nearest police officer. Patrolman Harvey McCauley happened to be walking his beat on Hancock Street at the time.

Sending Weldon to a nearby druggist to telephone police, McCauley broke down the door. William Place, unconscious, bleeding heavily and critically injured, lay just inside it. Weldon summoned police from the nearby Ralph Street station and two ambulances were hastily dispatched from St. Mary’s hospital. In the ambulances were Doctors Fitzsimmons and Gormully. From Ralph Street came Captain Ennis and Detectives Becker and Mitchell.

The first thing they noticed apart from William was a strong smell of natural gas. The doctors attended to William, rushing him immediately to St. Mary’s. Ennis, Becker, Mitchell and McCauley rushed upstairs to a front bedroom. Slamming open the windows to prevent an explosion they almost fell over a woman’s body wrapped in a quilt, a pillowcase obscuring her features. It was Martha. It was also Martha who had wrenched two gas taps so severely they couldn’t be completely shut off.

Weldon identified the prone figure immediately. As he did so a police cordon was hastily established to keep out the crowd gathering outside. One of the throng still managed to get inside. Ida’s sweetheart Edward Scheidecker was desperate for news that Ida was safe and well. He was to be horribly disappointed.

Identifying himself to Captain Ennis, Scheidecker asked for news of Ida. The officers had none to give until he took them to Ida’s bedroom. Ominously, the door was locked and had to be broken down. With McCauley guarding the door and keeping Scheidecker back Ennis, Becker and Mitchell burst into the room. What they discovered appalled everybody. The source of the acidic stench was now grimly apparent.

Beneath her own mattress Ida Place lay dead. Her face was horribly disfigured, Martha having thrown concentrated phenol over her. Had she lived Ida would have been both disfigured and totally blind, but she hadn’t. Not content with throwing a highly-corrosive chemical into Ida’s face, Martha had finished the job by suffocating her with a pillow. Bruises on her head and throat completed the awful picture. The smell of that chemical, which had already made Hilda Jans’s eyes water on the floor below, was so strong the officers were almost overcome.

Becker and Mitchell began a preliminary search while pathologist Alvin Henderson and Coroner John Delap assessed Ida’s body. It was Henderson who noticed the pillow stained with blood and reeking of phenol, suggesting immediately that Ida’s death had come in two stages. First the phenol, then the pillow. There was no doubt whatsoever that Ida Place had been brutally murdered. There could be little doubt by whom.

By now William and Martha Place were both at St. Mary’s. Martha recovered relatively quickly. William lay in critical condition for days, detectives only able to question him in short bursts. With his initial testimony concluded William was given a twenty-four-hour guard. With Martha’s room only two floors above her husband’s it was feared she might try to finish her handiwork.

Captain Ennis, Detectives Becker and Mitchell and Assistant District Attorney McGuire questioned William gently, pressing him as little as possible. Why had Martha done it? What had caused to her to commit one brutal murder and attempt a second? According to William it was down to the latest (and last) of their seemingly continuous series of altercations.

Martha had run up some extravagant bills. Despite her own considerable savings of nearly $1200 she hadn’t paid them and had no intention of doing so. Asw as so often the case with Martha, rules were for other people. The previous Saturday the couple had quarreled about both the bills and, yet again, Ida’s attitude. In response he had cut her allowance for that week, reallocating it to pay her bills:

“I told her ‘No more allowance for you this week. Your allowance money is going to help pay those bills. That only made her more furious. The argument began again on Sunday and she resumed it before breakfast on Monday. My wife threatened me. And not for the first time. ”Asked by McGuire, William elaborated further: “She stormed: ‘I want my money! If you don’t give it to me, I’ll make it cost you ten times more!’”

It was during his recovery that they had to inform him of Ida’s murder by her stepmother. Still lying seriously ill on his sickbed William immediately vowed vengeance: “If she has killed Ida, nothing you can do to punish Martha will punish her enough…”

McGuire had other ideas. Sing Sing, Auburn and Dannemora prisons all had something tailor-made to punish her and State Electrician Edwin Davis would do the punishing, but that was for later. First he had to have Martha charged with first-degree murder, attempted murder and attempted suicide (then a crime in New York State).

Martha was still feigning delirium two floors above, an act lasting only as long as it took detectives to gather enough evidence to charge her. For William’s safety she was moved to the Raymond Street jail to await trial. With his story in mind doctors and detectives concurred that she was simply shamming.

Rolling her eyes, writhing and periodically asking where her husband was cut no ice whatsoever. She may even have suspected he was still alive. If so there was only one likely reason for wanting to know where he was, to get to him before he talked. According to Detective Becker: “She has a cruel face, a cruel heart and she is a great actress.”

Beginning on 5 July 1898 Martha’s trial was a popular attraction. Judge Hurd presided, McGuire prosecuted and Martha retained eminent defense counsel. New Jersey lawyer Howard McSherry and New York’s Robert van Iderstine would fight her seemingly-hopeless case. A jury of twelve Brooklyn citizens would assess her guilt or innocence. If needed, Judge Hurd would pronounce sentence.

Depending on the jury Martha faced either life imprisonment or death if convicted. Whether the jury gave their recommendation for mercy would likely decide whether she faced life in a cell or death in the electric chair. With that in mind Martha’s lawyers chose an unusual strategy, a general denial of guilt. According to them she simply hadn’t done it.

McGuire begged to differ. His case was as solid as it could be and he knew it. Hilda Jans was sent away so she couldn’t interfere. Martha had recovered her bankbook, packed her trunk and ensured Hilda arranged its delivery to New Jersey via train, a state outside New York’s legal jurisdiction.

To make things worse, argued McGuire, she’d done all these things then gone about her daily chores while Ida lay dead on her bedroom floor. As if that wasn’t enough Martha had lain in wait for her husband with the axe, almost hacked him to death and feigned a suicide attempt. To McGuire that was simply a desperate ruse to elicit sympathy and cover her murderous tracks.

Martha’s cold and indifferent attitude did nothing to aid her case. If anything her icy, seemingly unrepentant attitude only made McGuire’s job easier. To the jurors she seemed exactly the sort of person to commit the crime she being tried for. Reporters assigned to the trial were equally unflattering:

“She is rather tall and spare, with a pale, sharp face. Her nose is long and pointed, her chin sharp and prominent her lips thin and her forehead retreating. There is something about her face that reminds one of a rat’s, and the bright but changeless eyes somehow strengthen the impression.”

Despite hiring expensive lawyers she managed to ruin their case within just one hour on the witness stand. Having previously claimed she had the axe in case William attacked her she told the court that she’d used it only after extreme provocation, not in self-defence. Her throwing concentrated phenol into Ida’s face before smothering her was, claimed Martha, also the result of extreme provocation. According to Martha her victims were to blame for provoking her and she hadn’t thrown the phenol intending to either disfigure or kill. Presumably, smothering Ida with the nearest available pillow wasn’t with homicidal intent either.

When cross-examined by McGuire she also refused to answer questions about where she’d obtained the phenol, which was a concentrated form not usually used undiluted. She also refused to say how long she’d had it, or to explain why its original container had vanished from the house. According to Martha she’d poured it into a cup immediately before the confrontation with her step-daughter, but no container was ever found.

It would have been impossible for Martha to admit owning it for any length of time without it looking like a premeditated purchase. She couldn’t say who or where she obtained it without detectives checking. If they had they would have caught her in another lie or perhaps found out exactly when, where and from whom it came. As it was her refusal to answer looked every bit as damning.

Her nemesis (and star prosecution witness) was husband William. He had no reason to lie nor any reason to say or do anything in her favor. Not surprisingly, he didn’t. Pathologist Alvin Henderson supplied damning medical evidence. Smothering her after throwing the acid obviously looked like a deliberate effort to kill an already-defenseless victim.

Hilda Jans described the events of that fatal morning. Captain Ennis, Patrolman McCauley, Detectives Becker and Mitchell, the Weldons and Ida’s sweetheart Edward Scheidecker had also bolstered McGuire’s case to the point where it became unassailable. Martha, however, remained indifferent. After deliberating less than four hours the jury delivered their verdict; Guilty as charged, without recommending mercy. After Judge Hurd passed sentence on 12 June 1898 Martha remained unmoved:

“Really, this is remarkable.”

Judge Hurd setting her first execution date was purely a formality. New York law guaranteed one mandatory appeal for condemned prisoners but after that they were on their own. No woman had been executed in the state since Roxalana Druse in 1887. After her botched hanging (Druse had strangled for fifteen minutes before she finally died) successive Governors and appeals courts had reprieved all women condemned to die. No Governor since David Hill had been willing to risk the electoral backlash of another botched female execution. Botched male ones, whether by the rope or the chair, earned far less scrutiny.

Druse’s death had fueled New York’s quest for a replacement for the gallows and also the abolitionist lobby. Shortly before her execution New York had even debated abolishing the death penalty for women while retaining it for men. The result had been a defeat for the so-called ‘Hadley bill,’ Druse’s execution and the arrival of the electric chair. Since the electric chair formally came into force in January 1889 two women had been condemned to electrocution, but neither had suffered it.

Martha Place was the first woman to sit in the chair, but the third condemned to it. Serial poisoner Lizzie Halliday had been condemned on 21 June 1894. Roswell Flowers commuted her sentence, sending her to the Mattawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. In 1906 she murdered psychiatric nurse Nellie Wicks, stabbing her over 200 times with a pair of scissors.

Maria Barbella had been condemned in 1895 for slashing her lover’s throat with a razor. Her first death sentence was overturned on appeal and a retrial began in November 1896. Sympathetic to her claims of having been raped by her abusive lover the second jury acquitted her entirely. She left court a free woman.

In contrast nineteen men had been hanged and forty-five electrocuted between Roxalana Druse’s hanging and Martha Place walking her last mile. Despite the brutality of her crime there was still some public opposition to her being electrocuted. Some even disputed the state’s right to electrocute her at all. Governor Theodore Roosevelt begged to differ, dismissing their position as “Mawkish sentimentality.”

New York’s courts afforded her no relief. Frank Black, 32nd Governor of New York, had had nothing to say on her case and that included granting her executive clemency. His successor was none other than Theodore Roosevelt. If Martha hoped Roosevelt had changed his mind she was to be sorely disappointed. On 15 March 1899, only five days before her scheduled execution, he turned her down flat, writing:

“The only case of capital punishment which has occurred since the beginning of my term as Governor was for wife-murder, and I refused to consider the appeals then made to me after I became convinced that the man really had done the deed and was sane. In that case, a woman was killed by a man, in this case, a woman was killed by another woman. The law makes no distinction as to sex in such a crime. This murder was one of peculiar deliberation and atrocity.

I decline to interfere with the course of the law.”

Barring a miracle, Martha’s place in criminal history and the electric chair were now firmly sealed. While passing the months, weeks and days left to her at Sing Sing’s death house Martha’s behavior had been erratic. Her priest had done much to calm her although she still became hysterical on several occasions. With the priest’s ministrations and a course of Bible study he’d managed to calm her down when her time came.

On 20 March 1899, exactly fifty-eight weeks after the murder, she met her fate calmly and without hysterics. Her demeanor in the death chamber was much the same as at her trial, cold and indifferent. Unlike male convicts her hair was elaborately styled rather than trimmed all over, hiding the unsightly patch of bare skin required for the head electrode. Never having electrocuted a woman before, Edwin Davis decided to place the leg electrode on her ankle rather than her calf.

Only twelve witnesses were there to watch her die. She entered the death chamber just before 11am dressed in black and carrying her Bible. She wore a white cord around her neck. This, she said, she’d been planning to wear if she’d been acquitted or eventually paroled. It took only three minutes for Davis and female prison officers to place the electrodes and buckle the heavy leather restraints. She sat calmly as this was done, uttering no sound, saying nothing except a faintly-heard final prayer:

“God help me; God have mercy.”

At 11:01 Davis threw the switch. 1760 volts seared through her body. Both the chair and Davis had come a long way since William Kemmler, this time there was no problem at all. A second jolt was delivered just to be absolutely sure before a female doctor and Sing Sing physician Doctor Irvine made their official checks. According to reporters she died almost immediately, Irvine later remarking that it was: “The best execution that has ever occurred here.”

After the autopsy required by state law she was returned to her native New Jersey and buried at East Millstone.

Wanting to avoid sensational press reports Roosevelt had quietly written to Sing Sing’s Warden Omar Sage, whose grim job it was to supervise her execution. Roosevelt was specific in his requirements on press representation Aside from the other official witnesses only reporters from the Associated Press and New York Sun were to be admitted. All others were to be kept out of Sing Sing’s death chamber. Going further Roosevelt explained why:

“I particularly desire that this solemn and painful act of justice shall not be made an excuse for that species of hideous sensationalism which is more demoralizing than anything else to the public mind.”

According to Denis Brian’s book ‘Sing Sing: The Inside Story of a notorious Prison’ Martha’s was also the first electrocution witnessed by a female reporter. New York Sun reporter Kate Swan was sent by no less than Joseph Pulitzer to cover the story. She was the last female journalist to do so for some time. Not until Nellie Bly witnessed the execution of Gordon Fawcett Hamby on 29 January 1920 would another woman enter Sing Sing’s death chamber except to die in it.

Perhaps the best explanation and kindest epitaph came from Martha’s brother Peter Garretson, then living in New Jersey. When told of his sister’s predicament he was distraught:

“When I reached Jersey City this morning I tried to go over to Brooklyn to see Mattie, but I couldn’t get up the sand. There isn’t the slightest doubt that she was insane. All these stories that she was jealous of Ida must be wrong. Why, she loved that little girl.

Ever since she was forced to let her son Ross go among strangers she has worried and fretted over that. She was wonderfully attached to him. I think brooding over her future to get the boy turned her brain, which was none too strong after a carriage accident.”

Since Martha Place New York executed very few women and not all for murder. Mary Farmer, Ruth Snyder, Anna Antonio, Eva Coo, Frances Creighton, Helen Fowler, Martha Beck and Ethel Rosenberg rounded out the list.

The wheel turned full-circle when Ethel Rosenberg entered the death chamber shortly after 8pm on 19 June 1953. Convicted with husband Julius of passing atom bomb secrets to the Russians, she died minutes after Julius amid world-wide media attention. Her death wasn’t as simple as Martha’s. Where Martha had died after her first jolt (the second had been just to make sure) Ethel required five to end her life.

It also ended the career of New York’s fourth State Electrician Joseph Francel. Francel, dissatisfied with the pay and loathing the publicity, resigned the next year after executing his 140th inmate. His place was taken by New York’s last executioner Dow Hover who officiated at New York’s last-ever execution, that of armed robber and murderer Eddie Lee Mays on 15 August 1963.

4 responses to “On This Day in 1890 -Martha Place, the first woman in the electric chair.”

-

[…] morte della donna, ma si rifiutò. Il 15 marzo 1899, cinque giorni prima della prevista esecuzione, motivò così la sua […]

-

[…] Davis and Hurlburt, it lacked the grim distinction of claiming a female occupant. That had been Martha Place, executed by Davis at Sing Sing on March 20, 1899. On May 1, 1916, though, Charles Sprague was […]

-

[…] Death House held some of America’s most notable criminals. In 1899 Martha Place, condemned for murdering her step-daughter, made criminal history as the first woman to be […]

-

Reblogged this on Crimescribe.

Leave a Reply