Your cart is currently empty!

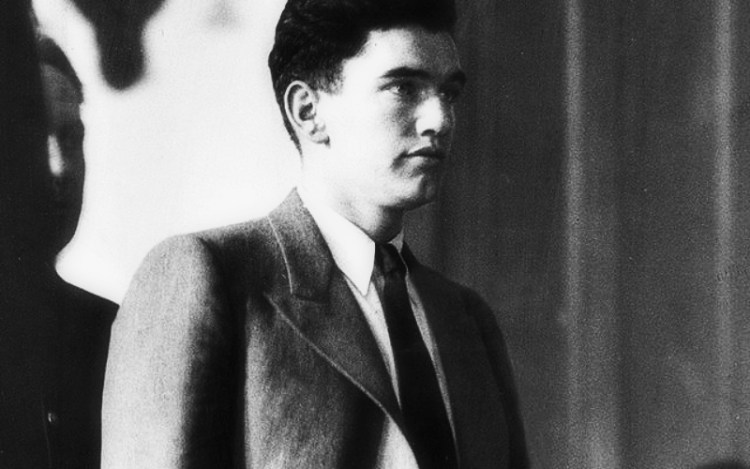

On This Day in 1932, Vincent ‘Mad Dog’ Coll is finally put to sleep.

Vincent ‘Mad Dog’ Coll was the archetypal wild, reckless, violent young gangster of the Prohibition era. Even at a time when crooks like Baby Face Nelson, John Dillinger and Al Capone inflicted violence and death on a regular basis, Coll managed to stand out as being especially vicious. An aura of complete recklessness, seeming unconcern…

Vincent ‘Mad Dog’ Coll was the archetypal wild, reckless, violent young gangster of the Prohibition era. Even at a time when crooks like Baby Face Nelson, John Dillinger and Al Capone inflicted violence and death on a regular basis, Coll managed to stand out as being especially vicious. An aura of complete recklessness, seeming unconcern with personal risk and utter indifference to violence hung around him like a bad smell.

Coll lost no time becoming the kind of gangster that people didn’t need to cross for him to hurt them. With so many powerful enemies, simply being in the same room was to risk taking a stray bullet. Not that Coll cared, it would have been their fault for being in the way.

Born in Gweedore, Ireland on July 20, 1908, Coll emigrated to the US a a year later. He later returned there believing the locals would offer their hometown boy made bad the traditional warm Irish welcome. They didn’t, knowing his brutal reputation even in rural Ireland they gave him the cold shoulder instead. As far as his fellow-countrymen were concerned he could take himself and his troubles back to Neew York where they belonged.

Whether Coll was born a sadistic psychopath is unknown, but it’s unlikely growing up in Hell’s Kitchen would have ironed out any psychological defects. Instead, Coll’s winning personality formed amid constant violence, crime and sudden death. By the time he was 12 Coll earned his first stint at reform school, rotating between reform schools and the streets for the next few years. Once the reform schools decided they couldn’t handle him Coll roamed the streets full-time, joining the notorious ‘Gophers’ street gang. Then as now, today’s street punks were tomorrow’s gangsters. Coll was no exception to the rule.

During the 1920’s Coll became one of many enforcers for beer baron Arthur ‘Dutch Schultz’ Flegenheimer, starting in his late teens. It wasn’t long before he committed his first murders. Anthony Borello owned a speakeasy and one of his hostesses was Mary Smith. Like most bootleggers Schultz had an aggressive sales policy, his ‘salesmen’ forced customers to buy his booze and nobody else’s.

Anybody refusing to buy or buying elsewhere could expect swift, brutal retaliation. Borello wouldn’t buy Schultz’s booze and Mary Smith just happened to be there at the time Coll arrived to deal with Borello. Naturally, Smith became a witness to the murder. Equally naturally (to him anyway) Coll murdered her as well. Allegedly through Schultz bribing and intimidating the jury, Coll was acquitted.

The relationship between Coll and Schultz was always contentious and often sour. Coll resented being Schultz’s employee, taking a junior position and an equally junior cut of the profits. Schultz viewed him as just another hired gun and Coll constantly groused about his meanness. When Coll performed an armed robbery at a New York dairy and taking $17,000 in cash Schultz was outraged.

With the law constantly on his trail the last thing Schultz needed was unnecessary police attention on him and his gang. To Schultz’s immense surprise (and equal fury) the worm had turned. Coll laughed at Schultz’s attempts to discipline him. Instead of humbly backing down Coll demanded an equal partnership. If he didn’t get it, he told his boss, Schultz himself wuld be abducted, ransomed and likely murdered

Schultz, himself notoriously temperamental, laughed at Coll’s demand to be made a full partner. He was enraged when Coll threatened his life as well. One of Coll’s other sidelines was kidnapping other gangsters for ransom knowing they they wouldn’t go to the police. They couldn’t, bound both by the underworld code of silence and that the taxman might ask where they’d obtained the ransom money. This caused fury among kidnapped gangsters and their friends and, while lucrative for Coll, created regular problems for Schultz. Coll was known to be one of Schultz’s gunmen and his actions reflected on his boss. Hence, the Schultz-Coll partnership never happened. The Schultz-Coll war certainly did.

It was during his war with Schultz that Coll reached his worst. It’s estimated that Coll and his (very few) recruits killed over 20 Schultz gangsters. Schultz’s men, in return, rubbed out several of Coll’s allies including his brother Peter Coll. One hit that went terribly wrong involved one of Schultz’s senior men, Joseph Rao. Rao was lazing outside a gangster hang-out on July 28, 1931 when a car pulled up on the sidewalk.

The car contained several men with Thompson sub-machine guns and shotguns unleashing a fusillade of lead and buckshot. They didn’t kill Joey Rao who escaped largely unhurt. They did shoot five children who were close to Rao when the shooting started. Four were seriously wounded, but survived. One, 5-year old Michael Vengalli, died soon after. Vincent Coll had now become ‘Mad Dog,’ also known as the ‘Baby Killer.’

All of New York, the straight world and underworld alike, was appalled. Honest citizens were appalled on general principle. They had to put up with enough gangland violence as it was without needless deaths of innocent bystanders especially children. The underworld were appalled too, not so much over collateral damage, but because they knew the slaughter would undoubtedly force a major police crackdown until Coll was either caught or killed. What they called the ‘big heat’ would be on with a vengeance. Only Coll’s capture or death would turn it off. While he still lived Coll was bad for business.

Whether Coll was caught by the police or underworld made no difference. With electrocution mandatory for murder in New York State at the time, Coll’s only choice was between a bullet from his underworld colleagues or a train ride to Sing Sing Prison’s dreaded ‘Death House’ quickly followed by a seat in ‘Old Sparky.’ One way or another he was doomed and Coll knew it. He didn’t seem to care.

He surrendered to police and was arrested to await trial. Fortunately for Coll he’d retained legendary defence lawyer Samuel Liebowitz (defender of Alabama’s Scottsboro Boys). First Joey Rao refused to testify, handing Coll a advantage. Sealing Coll’s seemingly-remarkable escape was the sole prosecution witness, George Brecht. Brecht was soon exposed by Liebowitz as having a criminal record, a history of mental health problems and of having made similarly inconsistent testimony in a different murder case in Missouri. With the star prosecution witness’s credibility destroyed the trial judge had no other option. He directed the jury to acquit and Coll walked free.

This wasn’t as good for Coll as it seemed. Granted, he’d evaded lawful justice, but gangland justice could be far swifter and equally deadly. While Coll remained alive, free and causing endless police attention wherever he went no gangster found it easy to do business. The anticipated police crackdown began and the only way to stop it was to deal with Coll themselves. Coll had few friends left in gangland. If the law couldn’t fix him then the underworld could, had to and did.

By now Coll was so complete an outcast that Prohibition bigshots ‘Dutch’ Schultz and Owney ‘ The Killer’ Madden both placed $50,000 bounties on his head. These were open contracts where any gunman could try his luck. Whoever killed Coll stood to collect a big bounty, gangland’s gratitude and the relief of respectable, honest New Yorkers. It wasn’t long before somebody collected.

On February 8, 1932 Coll was in a drugstore using a public payphone. He was on the phone to none other than Owney Madden himself and the conversation wasn’t friendly. To raise extra money Coll was openly threatening to kidnap Madden’s brother-in-law for a hefty ransom. Madden simply kept Coll talking. While they argued two triggermen raced to the drugstore hoping to find Coll still on the phone. He was and Madden’s gunmen abruptly terminated Coll and his conversation.

A car arrived outside the store. The driver stayed at the wheel while triggermen Anthony Fabrizzo and Leonard Scarnici entered the store, quietly urging the storekeeper to keep quiet. A long burst of machine-gun fire shredded the phone booth and Coll himself, leaving 15 bullets in his body. Unlike much of Coll’s handiwork, only the phone booth and Coll himself were hit by the bullets and nobody else was killed or wounded. It was a clean, precise professional job.The ‘Mad Dog’ had finally been put to sleep aged only 23.

Nobody involved seems to have done well out of Coll’s murder. Coll himself was buried at St. Raymond’s Cemetery beside brother Peter, himself a casualty of the Schultz-Coll war. The two brothers probably knew more peace in death than they ever found in life. Fabrizzo, one of three brothers to join the underworld, was murdered in November 1933. One brother had already been murdered in 1929. The other followed only weeks after Coll’s demise.

Scarnici continued carving a bloody trail through gangland until 1933, by which time he was suspected of at least a dozen murders. Convicted of murdering Detective James Stevens during a bank robbery in May 1933, Scarnici was sent to Sing Sing’s death house. On 27 July 1935 he was executed immediately after ‘Mallet Murderer’ Eva Coo, one of few women to face New York’s ultimate penalty.

Coo’s last words had been simple ones. Turning to the female matrons escorting her she said simply “Goodbye, Darlings.” Then she sat down and died. Scarnici arrived smiling and puffing on his last cigarette, casually greeting Warden Lewis Lawes as he walked in. With a tinge of smoke and burned flesh still hanging in the air, his final speech referred to people he believed had betrayed him:

“All I want to say is I want to send a message to the people in Albany, people who double-crossed me up there. I still say I’m a better man than they are. I thank you, Warden.”

The current flowed and Scarnici died. Coll’s old nemesis Schultz didn’t have long before following him. On 24 October 1935 he was having dinner with several of his top lieutenants at the Palace Chop House in Newark, New Jersey when Murder Incorporated gunman Charlie ‘The Bug’ Workman decided to join him. His henchmen died in a hail of gunfire and the mortally-wounded Schultz died days later. Worrkman later served a 23-year sentence for the murders.

One response to “On This Day in 1932, Vincent ‘Mad Dog’ Coll is finally put to sleep.”

-

Thanks for that. In my research on alcohol prohibition I noticed that legal problems of corn-sugar bootleggers coincided with major stock market, financial and banking problems. In the NY Times for 05OCT1931 I found “COLL SEIZED WITH HIS GANG, IDENTIFIED AS BABY KILLER…” Libertariantranslator

Leave a Reply