Your cart is currently empty!

On This Day in 1920 – Gordon Hamby’s Last Goodbye and Nellie Bly’s First Execution.

Bandit and burglar Gordon Fawcett Hamby was a strange bird by any standards. His death was a rarity at Sing Sing, the first time a female reporter had witnessed an execution there since 1899. That reporter had been Kate Starr working for one of the Hearst newspapers. Since then female reporters had never been allowed…

Bandit and burglar Gordon Fawcett Hamby was a strange bird by any standards. His death was a rarity at Sing Sing, the first time a female reporter had witnessed an execution there since 1899. That reporter had been Kate Starr working for one of the Hearst newspapers. Since then female reporters had never been allowed inside the death chamber though executed women were escorted by matrons and occasionally certified dead by female doctors.

That reporter was Nellie Bly, at least as fascinating a person as Hamby (with whom she corresponded for months before his execution). Born Elizabeth Cochran in Pennsylvania on 5 May 1864, Bly had already been a pioneer female journalist, blazing a trail that sets her apart even today.

Hamby, on the other hand, was a ruthless killer with an eccentric streak and an almost complete lack of normal human feeling. He would shoot at the drop of a hat but felt remorse when someone else was at risk of execution for his crimes. Even so Hamby, once caught and condemned anyway, did nothing to stop or even delay his own death at the hands of State Electrician John Hurlburt. It seems Hamby had as cold an attitude to his own death as to those of his victims. He refused to allow his lawyers to appeal and even asked the judge to condemn him. As quickly as possible. For a man who had fought his extradition to New York from Washington State this was a strange choice to make. To quote him exactly:

“I committed the crimes. It is right that I should pay the penalty.”

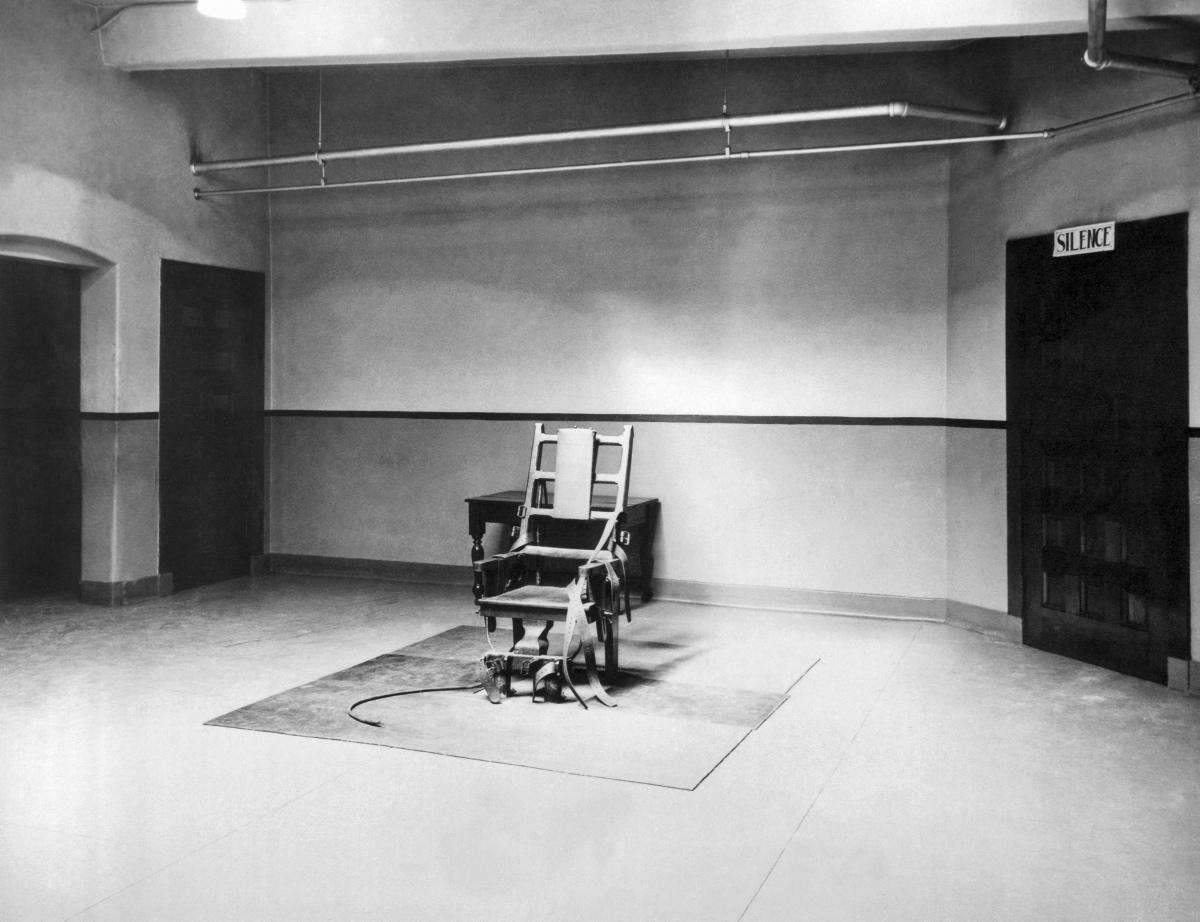

Pay he would, and far more quickly than today. Sentenced to die for a double murder committed during a Brooklyn robbery in December 1918, Hamby was extradited to New York in June 1919. He would die on 29 January 1920 after only a few months in Sing Sing’s purpose-built ‘death house.’ From robbing the East Brooklyn Savings Bank of $13000 on 23 December 1918 to his arrest in Tacoma, Washington in June 1919 he had been a fugitive for six months. Only another year lay between Hamby and the electric chair.

The Brooklyn robbery had been a disappointment to him:

“I expected to get $50000 out of the Brooklyn job and I was greatly disappointed with the little we did get. This was because my partner did not carry out my instructions. I had ordered him to jump over the rail the minute we entered the place, but he was an amateur and wasted too much time.”

True to the criminal code right to the last, Hamby refused to identify his partner-in-crime. It probably wouldn’t have changed his own sentence, but might have been grounds for a clemency plea if Hamby had wanted one. He didn’t and perhaps didn’t want anyone else succeeding on his behalf. A contradictory man, Hamby was as much at ease with the punishment as he’d been with the crime.

When he walked his last mile (actually only a few steps), Nellie Bly would be there to see it. A confirmed opponent of the death penalty, Bly was as revolted by Hamby’s execution as many were by his crimes. With a lengthy record including thirteen armed robberies, a train robbery and three known murders, Hamby wasn’t anybody’s idea of a good citizen, but a ruthless killer:

“I’m not a burglar, don’t insult me. I’m a regular, honest-to-God five-fingered worker. When I rob, I rob. When I kill, they stay dead.”

Even while waiting to die and seeing a half-dozen men walk through the ‘little green door’ ahead of him Hamby remained composed and impassive, even joking with death house guards right up until the switch was thrown. The Warden at Sing Sing, a newly-appointed death penalty opponent named Lewis Lawes, wasn’t joking. Hamby’s would be the second of Lawes’ two hundred or so executions, the first having been that of Vincenzo Esposito only eleven days earlier. He wasn’t looking forward to it.

After refusing to let his lawyers appeal Hamby didn’t mind at all. He even expressed his relief when a last-minute request for mercy (made without his approval) failed. During his brief time in the death house Hamby seemed so indifferent to his own death that a formal inquiry was made into his sanity. To his relief they lunacy commission found him legally sane and fit to die. He seemed far happier with his own imminent death than most of those involved in it. As Hamby himself remarked:

“The only interest I have is to see that I spend the time from now until I go to the electric chair in smoking, reading and making myself comfortable. I know there is no possible chance of acquittal. I am guilty and that is all there is to it.”

His seeming disinterest might have lain in his belief in reincarnation. Hamby kept a Ouija board in his cell, using it right up until he was escorted to the chair. Whether his lack of fear resided in believing he was only departing temporarily will never be known for certain, but he certainly seemed convinced of it:

“It is nothing for me to die because I am coming back. It may take a few years or it may take several thousand years, of course, but time does not count.”

Time might not have counted to Hamby, but it certainly counted to New York State. The authorities wanted an example made of this strange and ruthless criminal and wanted it made quickly. As curious a man as he was Hamby would be treated as any other condemned killer of the time. He would be condemned, warehoused and killed in short order. 29 January 1920 would see him sent off into the unknown, a journey that seemed not to bother him in the slightest.

Hamby’s personality had attracted Nellie Bly’s attention well before he made his final walk. She corresponded frequently with him in the months before his execution and, with better connections than most, was finally able to secure her own seat in the death chamber. For over two decades Sing Sing’s death chamber had been out-of-bounds to female reporters and in her usual fashion Bly would blaze yet another trail. It would not be to her liking.

Hamby’s execution was far from Bly’s first scoop. Her time as a foreign correspondent in Mexico had infuriated then-dictator Porfirio Diaz who had threatened to arrest her. Her undercover reporting from the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on New York’s Blackwell’s Island (‘Ten Days in a Mad-House’) had been a sensation, forcing reforms and making her name as an investigative reporter. In 1888 she’d managed to travel around the world in 72 days, beating the fictional Phileas Fogg by just over a week. Watching Hamby die would be the last big story of a glittering career before her death in 1922.

When the time came Hamby remained as coolly impassive as he’d always been. He declined to walk with a priest, remarking that to do so would be a mockery. When he took the few final steps between his cell and the chair he did so with a firm step. As he reached the chair he asked to make a final statement:

“I just want to say that any man who stood in front of Jay B. Allen’s gun had a chance. That’s all. Go ahead, boys.”

Seconds before the current flowed he made one final remark, a joke he’d been having with the prison doctor who he knew would signal the executioner:

“Where’s the red handkerchief, Doc?”

Doctor Amos Squire immediately gave the signal, a task he came to hate so much that he lobbied to make it the Warden’s job instead. That was it for Gordon Fawcett Hamby alias ‘Jay B. Allen.’ Hurlburt jerked the switch, worked his controls and in only two minutes Hamby was dead. After the attention his case had received it seemed almost anti-climactic, but without any problems. At least not technically, anyway. Bly, on the other hand, was absolutely revolted by the whole spectacle.

Just as Hamby had made his final statement on Earth, Bly made her final remark in her report of his execution:

“’Thou shalt not kill.’ Was that Commandment meant alone for Hamby? Or did it mean all of us..?”

One response to “On This Day in 1920 – Gordon Hamby’s Last Goodbye and Nellie Bly’s First Execution.”

-

[…] death chamber. Kate Starr cover Place’s execution. Not until pioneering female journalist Nellie Bly attended that of murderer Gordon Hamby in in January 1920 would another female reporter be […]

Leave a Reply to Sing Sing’s Death House – 1914 to 1963. – CrimescribeCancel reply