Your cart is currently empty!

On This Day in 1927 – Robert Greene Elliott executes six men in two US States on the same day

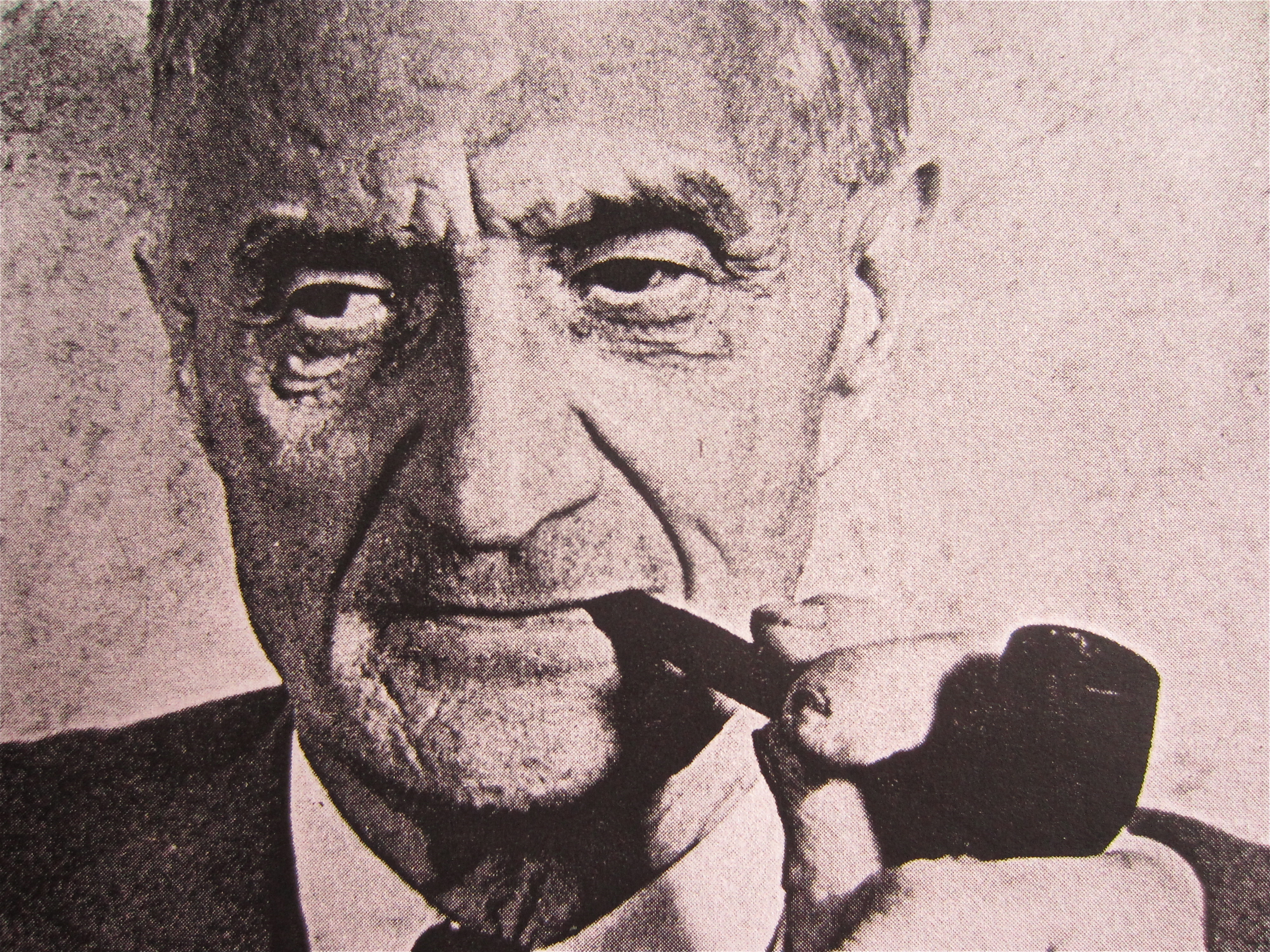

Robert Greene Elliott, ‘Agent of Death’ for six US States. Meet Robert Greene Elliott. Family man, devout Methodist, Sunday school superintendent, electrical contractor and pipe smoker. He also personally executed 387 people (including 5 women) working as a freelance executioner for six US States. Elliott was (and remains) the most experienced ‘State Electrician’ in penal…

Robert Greene Elliott, ‘Agent of Death’ for six US States.

Meet Robert Greene Elliott. Family man, devout Methodist, Sunday school superintendent, electrical contractor and pipe smoker. He also personally executed 387 people (including 5 women) working as a freelance executioner for six US States. Elliott was (and remains) the most experienced ‘State Electrician’ in penal history.

He became notorious Statewide, easily as well-known in New York as any of his victims and considerably better-known than most of them. Here we look at his busiest day in a 13-year career when American executioners were at their busiest, at a time when business was so brisk that Elliott himself executed six men in two different States on the same day.

On the morning of January 6, 1927 Elliot performed the first triple electrocution at the Massachusetts State Prison in Charlestown. Afterward he took a train down to New York City, spending a few hours with his family before taking another train to New York’s notorious Sing Sing Prison. At 11pm three men were taken from their cells in Sing Sing’s purpose-built ‘Death House’ and escorted one-by-one along their ‘Last Mile.’ Elliott, promptly and professionally as usual, electrocuted them all. His standard fee was $150 for executing one inmate. With double, triple and multiple executions then still common Elliott an extra $50 per head for executing two or more, earning himself $500 that day alone.

In his native New York, Elliott was as familiar a name as Ruth Snyder and Judd Gray, Bruno Hauptmann, Sacco and Vanzetti, Albert Fish or Francis ‘Two Gun’ Crowley. The Snyder case spawned the famous play ‘Machinal’ and film classic ‘Double Indemnity.’ Bruno Hauptmann was convicted of the Lindbergh baby kidnapping. Sacco and Vanzetti are still discussed as a miscarriage of justice. Albert Fish was a serial killer and cannibal and Francis Crowley inspired James Cagney’s most infamous screen villain ‘Rocky’ Sullivan in the crime classic ‘Angel with Dirty Faces.’

Elliott also claimed to be opposed to capital punishment and that it served no useful purpose. Odd really, considering his achieving notoriety in New York and 5 other States as their ‘Electrocutioner.’ It would probably have been curious to the 387 people he killed.

Elliot took the job in 1926 when predecessor John Hurlburt suddenly resigned after 140 executions. Both Hurlburt and Elliott had been trained by Edwin Davis, the world’s first State Electrician. Elliott held it until 1939 when he resigned and was replaced by Joseph P. Francel. Elliott died on 10 October 1939 (shortly after publishing his memoir ‘Agent of Death’) and Francel was announed as his replacement only two days later. Elliot’s memoir, long out of print and increasingly hard to find, covers some of his most notorious victims, the technical aspects of electrocution and his personal musings on both condemned inmates and capital punishment itself.

Original copies are both very expensive and equally hard to find, but it’s not as unusual as you might think for executioners to publish memoirs. Albert Pierrepoint, John Ellis, James Berry and Syd Dernley all left memoirs of their time working Britain’s gallows. In the US former Warden Don Cabana’s ‘Death at Midnight: Confessions of an Executioner’ is compelling if difficult reading. Mississippi’s ‘travelling executioner’ Jimmy Thompson never tired of interviews and photo opportunities involving his portable electric chair.

Generally speaking, executioners tend more to keep their lives and careers to themselves, shunning publicity in the same way that many people might shun executioners. They might applaud the executioner’s hand throwing a switch or pressing a button, but that doesn’t mean they always want to shake it in public.

Davis had been extremely touchy about being identified, once scolding Elliott at length just for using his surname in public. He even struck a deal with the railroad company running between his hmetown of Corning and Ossining (the nearest station to Sing Sing) to pick him up and drop him off at an isolated spot instead of an actual station. Hurlburt had been almost-paranoid, permitting no photogrpahs and loathing it when his name appeared in the press.

Small wonder that one reporter christened him ‘the man who walks alone’ although Hurburt did so for very good reason. Engaged to execute Alson Cole and Allen Grammer in 1920 (Nebraska’s first electrocutions) He’d been run out of town by local abolitionists and threatened with lynching if he ever returned. Cole and Grammer instead died at the hands of former Massachusetts executioner E.B. Currier, also trained by Davis and coaxed out of retirement for the occasion.

Hurlburt’s woes hadn’t ended with near-lynching in Nebraska either. Confined to Sing Sing’s infirmary after collapsing before and after a triple execution in 1925, Hurlburt spent his so-called rest cure terrified of what the hospitalised convicts might do if they even suspected his identity. The ‘burner’ (as Sing Sing inmates called him) knew just what to expect if they had.

Sing Sing’s most famous inmate, the dreaded ‘Old Sparky.’

In Massachusetts Elliott ‘burned’ John McLaughlin, John Deveraux and Edward Heinlein for murdering nightwatchman James Ferneaux during an attempted robbery in October, 1925. The then-infamous ‘Waltham Car Barn murder’ attracted great publicity at the time, not least because only Deveraux had fired the shot.

Despite this all three were convicted of the murder as they’d committed the robbery together. Legal concepts of ‘common purpose’ meant that if one member of a criminal group committed murder during some other crime (such as bank robbery, burglary or kidnapping for instance) then all involved were guilty. The fact that Ferneaux hadn’t died from the gunshot wound, but was finished off by being pistol-whipped made their appeals a formality.

At 7am Charlestown Prison, normally as rowdy and loud as any prison at breakfast time, was silent. Inmates and staff alike knew that this was the first time the State of Massachusetts had executed three men at once. Staff were worried about potential technical problems at the execution or unrest among the general population.

Inmates sat in their cells, silently watching the clock tick down to 7am. At the appointed time the three men died one after another without a hitch. Elliott had just made Massachusetts history, earning himself $250 ($150 for the first inmate and $50 each for the next two). His first job that day had run perfectly well. Three down, three to go.

According to one report Elliott simply returned to New York City and spent the next few hours with his family. They had dinner and saw a movie before Elliott headed for the railroad station. At Sing Sing executions were traditionally performed on Thursdays at 11pm, a grim tradition known to staff and inmates alike as ‘Black Thursday.’ Elliott reported to Sing Sing’s infamous ‘Death House’ (then one of the few purpose-built Death Rows in the country at the time) and prepared ‘Old Sparky’ for a ‘triple-hitter.’ He was ready to double his money.

Charles Goldson, Edgar Humes and George Williams were all condemned for joint involvement in a 1926 robbery and murder. While robbing a silk warehouse they murdered nightwatchman William Young. Goldson and Humes were only 22, Williams wasn’t much older at 26. Being over 21 they were still adults and liable for the death penalty, although at that time even juveniles could be executed and sometimes were.. Nothing really separated their crime from Elliott’s victims early that morning and neither New York’s appellate judges or State Governor thought them worth saving.

Like Charlestown, Sing Sing was quiet and not because it was late at night. Prisoners tend not to enjoy being near executions any more than most people. Executions often make prison staff uncomfortable as well. Inmates might riot in sympathy and not every prison officer supports the death penalty. Elliott arrived in mid-evening, inspected and tested the equipment and at 11pm did his job as professionally as at Charlestown.

Three more down, six in total, job done. Elliott earned himself $500 that day plus travel expenses. As a private contractor he had agreements with New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Connecticut. With six States and little sympathy for the condemned among judges and Governors, his tenure was a busy one.

Elliott was also technically skilled and is credited with perfecting the technique of judicial electrocution. His way became standard in numerous states and known as the ‘Elliott Technique.’ He routinely shocked a prisoner with 2000 volts for 3 seconds, 500 volts for the remainder of the first minute, up the voltage to 2000 for 3 more seconds and then another 57 seconds at 500 volts before a final 3-second burst at 2000. Such was his skill that a single two-minute cycle was usually enough. That was hardly surprising. Elliott was a consummate professional and had electrocuted his first man, Albert Koepping and Oscar Borgstrom, under Davis’s supervision in 1904. By 1927 he was a veteran.

Today’s executioners simply push a button and a computer-controlled process raises and lowers the voltage automatically. In Elliott’s time the equipment was manually operated. Elliott had to stand at his controls and turn the dials by hand, carefully watching the prisoner die while doing his job. If the voltage was excessive the inmate burnt alive. If it was insufficient they were slowly cooked so a skilled, experienced executioner was essential to avoid nightmarish mishaps. For doing that 6 times in one day $500 doesn’t seem like much.

A pretty curious abolitionist, really.

12 responses to “On This Day in 1927 – Robert Greene Elliott executes six men in two US States on the same day”

-

[…] Friend of the site Robert Walsh has a wonderful post detailing this character’s remarkable career; venture if you dare into the world of a prolific killer of the Prohibition and Depression eras, here. […]

-

John Devereaux was my great uncle. He suffered from post traumatic stress as a result of his service in World War I, but it was untreated and not identified at the time. Ironically, his father worked at the same prison in Charlestown but was forced to take a leave of absence when his son was incarcerated there. Hard to read that Elliot profited $150 in ending his life.

-

Thank you for getting in touch and my apologies for any upset I may have caused. It was certainly not my intention to do so. As a crime writer who does this for a living, it’s always something I try to keep in mind that real crimes involve real people and real consequences. It’s not just about things that people did, but also about who they were and the effects on their relatives are never to be ignored or dismissed. It’s not the first time I’ve had contact with relatives of people I’ve written about, and I thank you for getting in touch. Again, I do hope I haven’t caused any offence or seem to have shown you and your family any disrespect.

-

Absolutely no apology required. The article is fascinating and part of history. I am trying to track down Elliot’s book to see if there is info about my uncle, though debating if I want to read it. Thank you for the thoughtful response.

-

-

-

Another book on capital punishment and the effect it has on those who carry it out is: “The Last Face You’ll Ever See” by Ivan Solotaroff. The main focus is on Donald Hocutt, Captain of the guards and executioner/operator of the gas chamber in Mississippi’s Parchman Prison.

As a epilogue, Capt. Hocutt died in 2010 at the age of 55. -

Correction: Donald Hocutt’s rank was Colonel.

-

Article stated: “For doing that 6 times in one day $900 doesn’t seem like much.”

Doesn’t seem like much? $900 in 1925 is equivalent to $12,560.05 in today’s money, as stated on a currency calculator. Back then, $900 was a whopping amount of money for a day’s work, and you should make that clear to the reader.

-

Agent of Death now available on ebay https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/162827746513

-

[…] On January 6 1927 he set a record never likely to be repeated. Booked by Massachusetts to execute John McLaughlin, John Devereux and Edward Heinlein at Charlestown just after midnight, Elliott did so without incident. His day’s work was far from done. Returning to New York he spent a few hours with his family before driving to Sing Sing. At 11pm he executed Charles Goldson, Edgar Humes and George Williams. Six prisoners in two different states in one day. […]

-

[…] Terrified by so narrowly escaping death himself, Hurlburt never returned to Nebraska. Hurlburt’s successor Robert Greene Elliott (executioner of nearly 400 convicts during his tenure) had been hired by New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Connecticut between 1926 and 1939. It had been Elliott who executed Bert Stacey back in 1932. America’s most prolific executioner, Elliott once performed two triple electrocutions in different states on the same day. […]

-

[…] They earned $150 for single executions. Multiples paid $50 per additional inmate. A private contractor, New York’s executioner could also work for other States and usually did. Elliott, credited with 387 executions, was employed by New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Vermont and Connecticut. On January 6, 1927 Elliott performed a triple electrocution in Massachusetts just after midnight, then visited Sing Sing for another triple execution at 11pm. He was and remains America’s only executioner to kill six people in two different States on the same day. […]

-

[…] accounts from previous executions suggest otherwise, that a variation of the methods perfected by Robert Greene Elliott back in the 1920’s and 1930’s is still in use. The ‘Elliott Method’ or […]

Leave a Reply