Your cart is currently empty!

On This Day 1920 – Alson Cole and Allen Grammer, Nebraska’s first electrocutions (and almost executioner John Hurlburt).

Nebraska isn’t a particularly hard-line state for capital punishment. Since achieving statehood in 1867 it has executed only 48 people; 14 by hanging, 23 by electrocution and one by lethal injection. Today we’re going to look at murderers Alson Cole and Allen Grammer, Nebraska’s first to be electrocuted and the only double execution since Nebraska…

Nebraska isn’t a particularly hard-line state for capital punishment. Since achieving statehood in 1867 it has executed only 48 people; 14 by hanging, 23 by electrocution and one by lethal injection. Today we’re going to look at murderers Alson Cole and Allen Grammer, Nebraska’s first to be electrocuted and the only double execution since Nebraska became a state. What make this one particularly interesting is that the event almost cost the life of a third man, New York’s State Electrician John Hurlburt.

An executioner since 1912, Hurlburt was a veteran of the death chamber having performed dozens at New York’s Sing Sing, Auburn and Dannemora prisons, just the man Nebraska needed for the job. He could supervise the preparation and even perform the execution to ensure all went as planned. With that in mind Nebraska State Penitentiary Warden W.T. Fenton promptly engaged his services, an unusual out-of-state job for Hurlburt. Had things run to plan he probably would have but, for Hurlburt anyway, they didn’t. He would leave Nebraska never to return and lucky to still be alive.

Noe every Nebraskan supported capital punishment. Fewer still supported replacing the old gallows with the new-fangled electric chair, either. Hurlburt, already in Nebraska to supervise its debut, soon had this made abundantly clear and in brutally ironic fashion. He was warned of plans to halt the executions and that one group of abolitionists had a particularly ironic method in mind;

Lynch the executioner.

Yes (and presumably with no sense of irony, a group of local abolitionists were preparing to protest against a legal electrocution with an entirely illegal lynching. Tipped off in advance, Hurlburt decided discretion was the better part of valour. He immediately left the state, never to return.

For Warden Fenton this was an unexpected spanner in the works. He still needed somebody to run things and experienced electrocutioners were a rare breed even in the 1920’s when Old Sparky was its busiest. Fortunately for Fenton another man was available. Enter E.B. Currier, formerly executioner for Massachusetts.

Though having retired from that role Currier was prepared to come to Nebraska and finish what Hurlburt had started, hopefully without being lynched in his place. When not executing total strangers Currier lived on a farm near Boston. While dispensing death at Charlestown Prison he had worked, ironically, at the Massachusetts General Hospital as its chief electrician and mechanic. Whether his work colleagues or the patients knew of his side-line we don’t know.

Currier had installed the Massachusetts chair in 1898, Vermont’s in 1913 and helped install New Jersey’s in 1906. Like Hurlburt and Hurlburt’s successor Robert Elliott, Currier had apparently been an assistant of Edwin Davis (New York’s and indeed the world’s first State Electrician). When Hurlburt did his first job as State Electrician (George Coyer and Giuseppe DeGoia on 31 August 1914 at Auburn Prison in New York) it had been anticipated that Curier would replace Davis, not Hurlburt.

Davis had resigned in a fee dispute hwen his pay was cut. Originally receiving $250 per prisoner, New York mandated he should receive only $150 with an extra $50 per prisoner every time he executed more than one. Davis, who found executions a lucrative business, was unhappy and assistant Currier was unavailable, probably because he’d gone to Massachusetts to work their electric chair. With Davis and Currier gone, coyer and DeGoia died by Hurlburt’s hand, the first of his 140 executions before abruptly resignin in 1926 and taking his own life three years later.

Both a technical expert and thoroughly professional, Currier was as good a choice as anyone. With former colleague Hurlburt fleeing Nebraska for his life, Currier took the job. With the chair built and installed and somebody found to work it, all that remained was for Nebraska justice to provide somebody to sit in it. Enter Allen Grammer and Alson Cole.

Condemned for murdering Lily Vogt (who also happened to be Grammer’s mother-in-law) in 1917 Grammer and Cole had fought hard, their case taking almost three years to reach its end. With their appeals exhausted and Nebraska keen to demonstrate its new method, they were scheduled to enter state history on 20 December 1920.

It proved a busy day at the state prison. Currier having prepared thoroughly for the task in hand, he was able to make his final checks and relax as much as he could under the circumstances. The officers guarding Grammer and Cole had a rather busier time of it. Reporters came and went, keen to cover a singular event in Nebraska history. Grammer’s wife came to visit despite his having murdered her mother, being disowned by her remaining family as a result. Their lawyers came to say goodbye and Reverends McFadden, Gregory and Maxwell took care of their spiritual needs as best they could.

Hurlburt would have recommended the man most likely to cause trouble be taken first, keeping to Sing Sing’s standard practice. As both men had offered to go first and showed no sign of cracking it was down to Warden Fenton to make the choice; Grammer would go first at 3pm with Cole immediately following him. It was decided by Fenton having the pair’s defense lawyers guess the date on a coin in Fenton’s pocket. Whichever lawyer guessed the nearest year would see his client go second and Cole’s attorney won. Allen Grammer would have the dubious distinction of suffering Nebraska’s very first electrocution.

At 2:39pm the final act began. Fenton visited first Grammer and then Cole to bid them farewell. He also had to read them their death warrants while the six official witnesses took their places. Fenton allowed the pair a brief moment together for their final farewell. Thirty-five minutes later it was time for Allen Grammer to walk his last mile.

Neither man showed any fear when the time came. Grammer walked in a little after 3pm, . Currier and the five men assisting him worked quickly, having him securely strapped and capped in under a minute. At Fenton’s signal, Currie threw the switch delivering several jolts or around 2000 volts each and Grammer was dead. His final words had been simple ones to Fenton:

“Goodbye, Warden.”

Now it was Cole’s turn. He was a little more talkative than Grammer, asking whether prosecutor Charles Dobry was still present. He wasn’t. Perhaps one electrocution had been enough or more than Dobry could stomach and he’d left the death chamber after Grammer’s death. Minutes later Alson Cole joined his crime partner in the prison morgue.

Grammer was later buried at Rose Hill Cemetery in the town of Palmer in Merrick County. Cole, however, went to the Wyuka Cemetery in Lincoln County, later notorious for the killing spree of Charles Starkweather. Executed in the same chair n 1959 Starkweather too lies in Wyuka, a cemetery shared by some of his victims.

Even after the Hurlburt debacle Nebraska continued identifying its executioners long after Cole and Grammer met their ends. After Currier’s final retirement a few years later, New Jersey’s executioner took the job. Whether ‘W.S. Gilbert’ (whose namesake formed one part of theatre’s Gilbert and Sullivan partnership) was his real name or borrowed for the occasion, ‘Gilbert’ was eventually replaced by Hurlburt’s successor as New York’s executioner Robert Elliott.

In the 1940’s Nebraska finally decided (as Hurlburt had long believed) that anonymity was the best policy. Officially its executioners were no longer publicly named for their protection, the lessons of Hurlburt’s near-lynching having finally been learned. Ironically Nebraska’s electric chair, seldom used even in its heyday, outlived all the others.

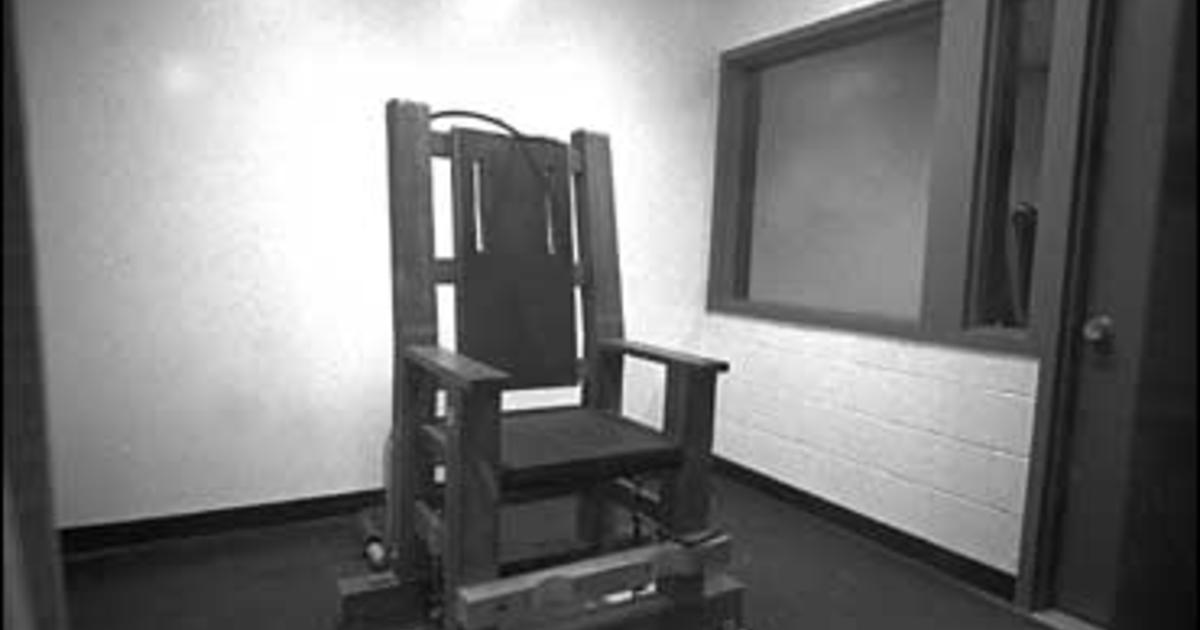

Nebraska was the last remaining state to offer electrocution as its sole remaining method and there has been only one lethal injection since Old Sparky was dismantled and put into storage. Ruled unconstitutional by Nebraska’s courts in 2008, it was replaced by lethal injection the next year.

Despite requests to borrow it as a museum piece Nebraska authorities have always refused, believing it simply isn’t something they want put on display. Nor too has Nebraska’s death penalty escaped scrutiny. It has been suspended, repealed, reinstated, suspended again and reinstated again, but currently remains in force.

Since 1976 only four convicts have been executed, three by electrocution and one by lethal injection in 2018. The last electrocution was that of Robert Williams on 2 December 1997. Carey Dean Moore, Nebraska’s only lethal injection to date, died on 14 August 2018.

4 responses to “On This Day 1920 – Alson Cole and Allen Grammer, Nebraska’s first electrocutions (and almost executioner John Hurlburt).”

-

[…] Hurburt did so for very good reason. Engaged to execute Alson Cole and Allen Grammer in 1920 (Nebraska’s first electrocutions) He’d been run out of town by local abolitionists and threatened with lynching if he ever […]

-

[…] Like Davis, Hurlburt had been a stickler for anonymity. He had been livid when the media published his name and, despite their best efforts, he always managed to stop them taking his photograph. That hadn’t helped him in Nebraska in 1920 when he narrowly escaped a lynch mob after being hired to perform the state’s first two electrocutions, Allen Grammer and Alson Cole. […]

-

[…] New York’s John Hurlburt had nearly been lynched and fled Nebraska when hired for that state’s first electrocutions. His place was taken by veteran ‘State Electrician’ E.B. Currier, former executioner […]

-

[…] appeals will prevent electrocution remains undecided. Other former electrocution states including Nebraska and Georgia have seen it declared unconstitutional by their state […]

Leave a Reply