Your cart is currently empty!

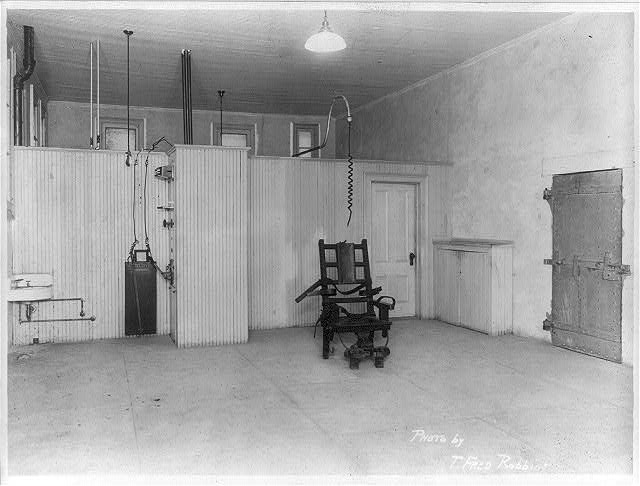

A Deadly Debut, Robert Elliott’s First Execution.

Robert Greene Elliott, State Electrician for New York and five other states, is often listed as making his official debut in January 1926 when he executed Emil Klatt and Luigi Rapito. They’re often said to be the first of the 387 state and Federal prisoners Elliott executed during his thirteen-year tenure as executioner. They were…

Robert Greene Elliott, State Electrician for New York and five other states, is often listed as making his official debut in January 1926 when he executed Emil Klatt and Luigi Rapito. They’re often said to be the first of the 387 state and Federal prisoners Elliott executed during his thirteen-year tenure as executioner. They were not, Elliott’s debut occurred as early as 1904 during the tenure of his predecessor Edwin Davis.

Davis, the world’s first State Electrician, executed 240 convicts, owned patents on several parts of the electric chair and trained two assistants. John Hurlburt succeeded Davis after Davis retired in 1912. Hurlburt, who resigned in 1926 after 140 executions and took his own life in 1929, was in turn replaced by Elliott. Eliott was the third of New York’s State Electrician and also its most prolific.

Elliott is also credited with evolving the so-called ‘Elliott Technique’ or ‘Elliott Method.’ 2000 volts for three seconds, 500 for fifty-seven seconds, 2000 for another three seconds, 500 for another fifty-seven seconds and a final few seconds at 2000 volts before shutting off the power.

It was quick, effective and seldom required more than a single cycle although New York usually expected two cycles just to make sure. Elliott, America’s most experienced ‘electrocutioner,’ is perhaps its most skilled, but it wasn’t always so. In fact, Elliott’s debut almost proved as lethal to one of the attending physicians as to the condemned man himself.

The man in question was 22-year-old Albert Koepping, condemned for the murder of former acquaintance John Martine at Martine’s Port Jervis home on 19 February 1903. Koepping always claimed self-defence. Having been evicted from the Martine home Koepping returned for his belongings and, he claimed, took a pistol in case Martine attacked him. According to Koepping Martine did exactly that and Koepping had no choice but to shoot him four times.

It was the line Koepping maintained right up to his execution, not that it held any water with the jury, trial judge, appellate judges or New York Governor Benjamin Odell. Nor did it matter to State Electrician Davis who saw it as just another execution. It didn’t mean anything to Elliott, either. Making a successful debut was far more important to him than whoever was sitting in Old Sparky at the time.

As it turned out Albert Koepping didn’t die alone. Oscar Borgstrom had murdered his wife in Port Kiscoe on Easter Monday the previous year. His stepdaughter witnessed the murder and Bergstrom was rushed through possibly the fastest murder trial in New York history. He was tried convicted and condemned to die in only five hours, spending more time at Sing Sing’s notorious Death House than he had awaiting trial.

For the morning of 13 June 1904 Warden Johnson decided the running order. Koepping would die first, at Elliott’s hand under Davis’s supervision. Bergstrom would be executed by Davis with Elliott doing his usual duties as assistant. A double execution was standard practice at Sing Sing and the only difference between this and any other was Elliott taking far greater involvement than usual.

The number thirteen is often regarded as unlucky due to its long association with executions. According to legend there are always thirteen steps to the top of a scaffold and the hangman’s knot always has thirteen turns of the rope. Neither happens to be true, but thirteen was nobody’s lucky number except Elliott’s and perhaps one of the attending doctors.

Counting Koepping and Bergstrom there were thirteen condemned inmates in the Death House that day. They both died on the thirteenth of June. Bergstrom had murdered his wife on the thirteenth of the month and. Thirteen minutes after Koepping received his first jolt Bergstrom received his own. The thirteenth letter of the alphabet is, of course, the letter M for murder, the number appears in numerous gang tattoos today.

Koepping, still claiming innocence, went first. Claiming innocence to the last he was quickly seated, strapped and capped. For the first time in his career it would be Elliott, not Davis, who threw the switch. Elliott’s memoir Agent of Death (released in 1940 the year after Elliott’s own death) takes up the story:

‘’Now,’ whispered Davis. I threw the switch, and the condemned man stiffened under the straps. In aa few seconds, Davis said, ‘Cut it down.’ I reduced the amount of current, and the body slumped. Finally, after the necessary number of shocks, it was decided that justice had been done. I went over and unfastened the head electrode. What had once been a living man was removed from the chair, and wheeled into the autopsy room. I had killed him.’

Elliott neglected to mention that he had almost killed a doctor as well during Oscar Bergstrom’s execution. Brought in only minutes after Koepping had been wheeled into the adjoining autopsy room, the strongly-built and muscular Bergstrom needed a third jolt to ensure his death. According to a report in the Kingston Daily Freeman, Elliott had been about to administer another jolt when Davis took a firm grip on his hand to stop him throwing the switch again. The reason, according to the Freeman reporter, was this:

‘A faint pulsation could be detected and a third shock was advised. The hand of the assistant electrician was upon the lever about to turn on the current a third time when Electrician Davis grasped him by the arm. One of the doctors had his ear to the stethoscope which was pressed over the man’s heart. The doctor was warned in time to prevent what might have been a serious incident.’

It made no difference. Koepping and Bergstrom were dead. The doctor survived unscathed. Davis continued as State Electrician until his retirement in 1914 after 240 executions including seven in one day. John Hurlburt took over until his own resignation in 1926 and then, with no other viable applicant for the job, Elliott replaced him in 1926 and conducted another 387 executions in six different states. Elliott was replaced in 1939 by Joseph Francel, his last execution was that of Arthur Perry on 24 August 1939.

Robert Greene Elliott died of heart problems on 10 October 1939. His career and that of all New York’s five State Electricians, appears in my forthcoming book ‘Murders, Mysteries and Misdemeanors in New York,’ out on November 25.

3 responses to “A Deadly Debut, Robert Elliott’s First Execution.”

-

[…] was hardly surprising. Elliott was a consummate professional and had electrocuted his first man, Albert Koepping and Oscar Borgstrom, under Davis’s supervision in 1904. By 1927 he was a […]

-

[…] official debut but not his first throw of the switch. On June 13 1904 he had executed Oscar Borgstrom and Albert Koepping at Auburn under Davis’s supervision. Elliott’s career ended with his 387th execution, […]

-

[…] 1890 and 1963, officially titled ‘State Electricians.’ Between them Edwin Davis, John Hurlburt, Robert Elliott, Joseph Francel and Dow Hover executed 614 inmates in New York alone. Potential applicants had to […]

Leave a Reply