Your cart is currently empty!

On This Day in 1964 – The Last Executions In Britain.

As regular readers are aware, I cover true crime here and the death penalty is a regular feature. Being an abolitionist, it’s with some small satisfaction that we’re going to look at Britain’s last executions. To the minute, if you happen to be reading this at 8am. On August 13, 1964 Gwynne Evans and Peter…

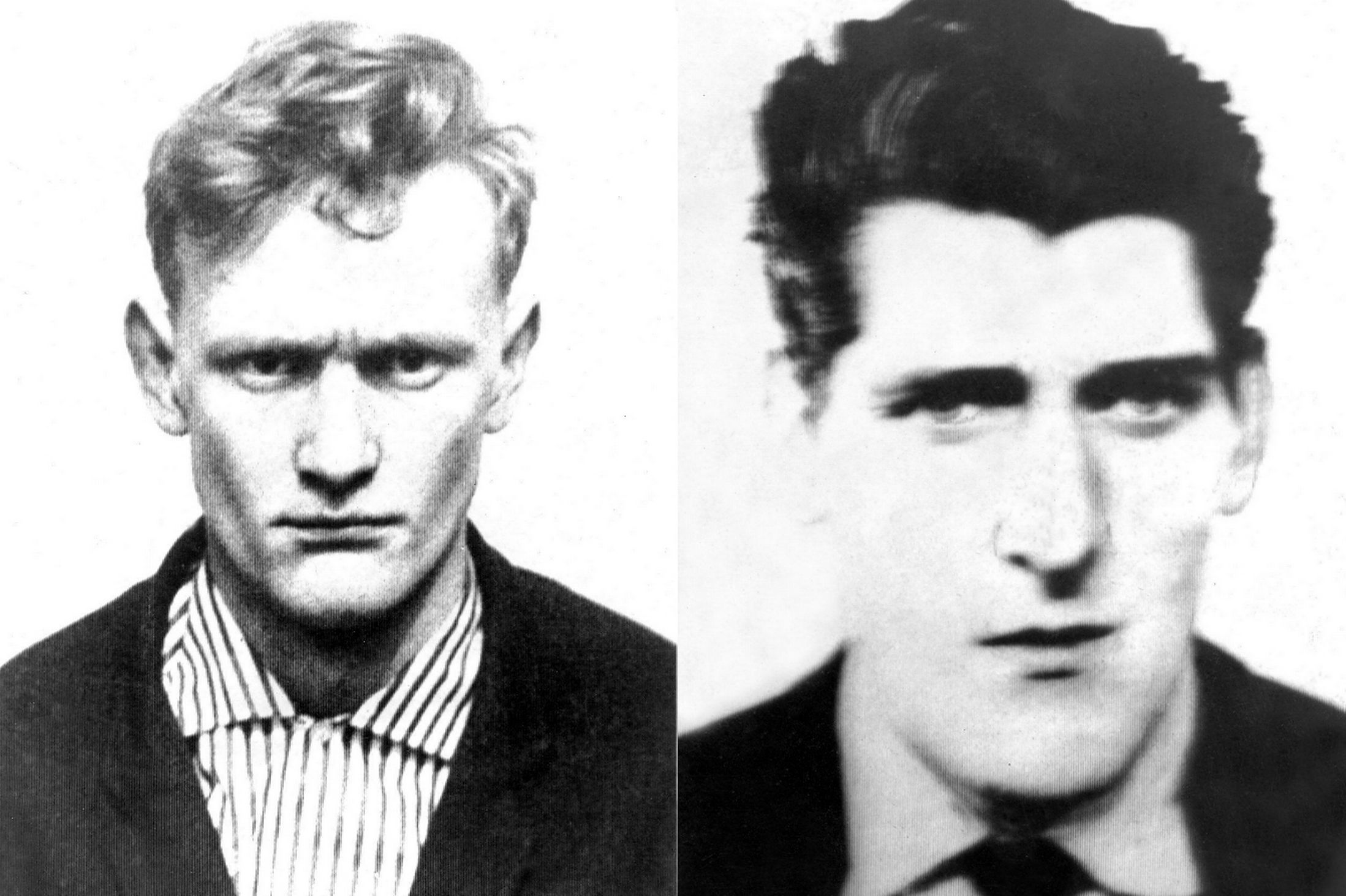

Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans, the last British inmates to hang.

As regular readers are aware, I cover true crime here and the death penalty is a regular feature. Being an abolitionist, it’s with some small satisfaction that we’re going to look at Britain’s last executions. To the minute, if you happen to be reading this at 8am. On August 13, 1964 Gwynne Evans and Peter Allen took their unwilling place in British penal history as the last-ever inmates to suffer the ‘dread sentence’, be taken to one of Her Majesty’s Prisons and keep their date with the hangman.

Well, hangmen, actually. Evans paid his debt to society at HMP Strangeways at the hands of Harry Allen (grandfather of comedienne Fiona Allen) assisted by Harry Robinson. Allen paid his at HMP Walton at the hands of Scottish hangman Robert Leslie Stewart (known as ‘Jock’ or ‘The Edinburgh Hangman’) assisted by Royston Rickard.

Their crime was unremarkable (not that any murder is a trivial matter) and their executions were equally standard affairs except for the fact that they were the last in British penal history. Judges would continue to don the dreaded ‘Black Cap’ and pass the ‘dread sentence’ until 1969 (the 1970’s in Northern Ireland). The death penalty was retained for several crimes other than murder until 1998 and its final repeal under the European Human Rights Act. But the noose and scaffold had already been consigned to history and the occasional prison museum.

Never again would the prison bell toll or the black flag be hoisted just after eight or nine in the morning. No longer would crowds gather outside a prison’s gates in protest at what was happening inside.. No more would a prison warder have to brave an angry crowd to post the official announcement on a prison gate. After centuries of State-sanctioned killing ranging from the deliberately-barbaric to the scientifically-precise, ‘Jack Ketch’ had finally put away his noose and passed into history.

Not that this was any consolation whatsoever to Evans and Allen. As far as they were concerned it made no difference at all and nor did it to anyone else. They still had to sit in their Condemned Cells at Walton and Strangeways, guarded 24 hours a day by prison warders and hoping every day for a reprieve that never came. Prison staff and the hangmen still had to report for duty as instructed and ensure that everything was prepared properly down to the finest detail.

The Appeal Court judges and Home Secretary still had to discuss, debate and ponder their decision, knowing all the time that if they refused clemency then these two deaths would be as much their responsibility as that of the executioners themselves. The families and friends of the condemned had no easier time than the condemned themselves. Allen and Evans would die, but their friends and families would still have to live with that afterwards.

Their crime was brutal, their guilt undeniable. Given the evidence against them there was almost no chance of their being acquitted. To manage that would require lawyers possessed of both boundless talent and equal optimism. If they did ever stand a chance of avoiding the gallows then it was far more likely to be through a reprieve than an acquittal. Barring a reprieve or a legal blunder serious enough to impress the Court of Criminal Appeal, their race was run. They probably knew it.

Evans and Allen were both typical, garden-variety condemned inmates. Under-educated, lower IQ’s than usual, failed to hold down any job for very long and with a string of petty criminal convictions between them. Fraud, theft, deception, the usual type of relatively low-level crimes that see a person in and out of trouble on a semi-regular basis, but nothing to suggest that either was capable of brutal, cold-blooded murder. Then again, a great many brutal, cold-blooded murderers have been described as not being ‘the type’ even though there’s no ‘type’ to watch out for. It would make the lives of honest people and detectives so much easier if there were.

Aside from not seeming the type, Allen and Evans weren’t exactly criminal masterminds either. After beating and stabbing to death Alan West in his home during a bungled robbery on July 7, 1964, Evans in particular left a trail of evidence that Hansel and Gretal would have been proud of. He left a medallion at the crime scene with his name inscribed on it. When he was dumping the stolen car used in the crime Evans dumped it at a local builder’s yard. He’d made himself so conspicuous (and, to a neighbour, highly suspicious) that it wasn’t long before he found himself in custody. Being found in possession of the victim’s gold watch probably didn’t help his case either.

Once under questioning Evans excelled himself even further. Initially he denied being involved. On realising he’d left a smoking gun with his name on it at the scene he decided to bury Peter Allen. To save himself from a charge of capital murder he’d put all the blame on his accomplice. Evans denied having a knife during the robbery and clearly blamed Allen for stabbing West to death. His ploy might have worked a great deal better but for one small problem; Evans’s own big mouth.

Being keen to bury his crime partner and possibly save himself, Evans talked loud and often. A little too loud and often as it turned out. Evans was loudly denying his having had or used a knife to murder Alan West. It was then that police pointed out to him that they hadn’t actually mentioned a knife, nor had they released that information to the press.

Bottom right: Harry Allen and Robert Leslie Stewart, their executioners.

Allen was now also in custody and being questioned. Both killers were under lock and key within 48 hours of committing their crime, a pretty fast resolution to a murder investigation. By modern American standards, their road from trial to execution would certainly seem faster still. One of the principle complaints of America’s pro-execution lobby is that the appeals process takes far too long. There are too many levels of court, too many technicalities, too many bleeding-heart pro-bono lawyers, too many soft judges and State Governors who refuse to allow what a judge and jury have already decided to hand down.

While it’s still groused about in the US, it was never the case in Britain. A condemned inmate was granted a minimum of only 3 Sundays between sentencing and execution. That didn’t mean an execution always happened 3 weeks after a sentence due to appeals, finding new evidence, court schedules, sanity hearings and so on, but 3 Sundays was all you could expect as of right. Miles Giffard, hanged at Bristol in 1953, spent only 18 days between sentencing and execution.

After sentencing the judge would send a private report including their opinion on whether a prisoner should be reprieved. Their reports weren’t always heeded, but they had more influence than any other factor in deciding whether prisoners lived or died.

Avenues for appeal were both smaller in number and moved a great deal faster than their American counterparts. After sentencing the first stop was the Court of Criminal Appeal. Appeals against conviction and sentencing were heard by a panel of 3 judges, often including the Lord Chief Justice unless he’d presided at your trial. If they rejected the appeal the next stop was the Home Secretary (nowadays the Minister of Justice). If the Home Secretary refused clemency the case file would be annotated with a single phrase;

‘The Law must take its course.’

Prisoners could still appeal to the King or Queen, but this was effectively pointless. By one of the many unwritten rules so beloved of British officialdom, the Monarch didn’t grant appeals except on the private advice of the Home Secretary. A Home Secretary (also a Member of Parliament so an elected official) might want to obey or defy public opinion by granting a reprieve while risking their job if they were seen to do so.

The Monarch, on the other hand, not having to consider their approval rating, could grant an appeal thereby saving a prisoner without causing problems for the elected officials concerned. But, regardless of whether a prisoner appealed directly to a Monarch, without a Home Secretary’s advice there would be no reprieve. Nobody involved felt merciful towards Evans and Allen.

Their trial began at Manchester Assizes on June 23, 1964 with Mr. Justice Ashworth presiding. Leading for the prosecution was was Joseph Cantley, QC (Queen’s Counsel, a senior lawyer) while Allen was defended by lawyers F.J. Nance and R.G. Hamilton. Evans was represented by Griffith Guthrie-Jones, QC. It didn’t take very long. Even the best of defenders couldn’t have won a verdict of not guilty. With Evans’s many and varied blunders he was effectively doomed from the start. Allen’s wife was the star prosecution witness, testifying that she’d seen Evans dispose of the knife and that Allen had made incriminating remarks in her presence

Not surprisingly both were convicted. As their murder was committed during a robbery it qualified as capital murder under the 1957 Homicide Act. This Act, brought in after the 1955 execution of Ruth Ellis, drastically altered capital punishment in Britain. It clearly defined the difference between capital and non-capital murder, dispensing with a mandatory death sentence and allowing judges, prosecutors and juries some discretion.

Before the 1957 Homicide Act jurors in particular were quite limited in their options. They could acquit a defendant, find them guilty but insane (avoiding a death sentence), guilty with a recommendation for mercy or simply guilty as charged. For non-capital murder life imprisonment was the sentence. If convicted of capital murder the sentence remained death.

The Act also enshrined diminished responsibility into English law for the first time, largely a response to the Ellis case. This wasn’t done to limit the number of executions per year, but to ease the minds of jurors in particular that a death sentence, when imposed, had been the correct decision. In practice, a jury’s recommendation for mercy carried far less weight than the trial judge’s confidential report.

With Evans and Allen convicted of capital murder Justice Ashworth then took his own place in British penal history, becoming the last British judge in a British courtroom to don the dreaded ‘Black Cap’ (a square of black silk placed atop a judge’s wig as a gesture of mourning for the newly-condemned and recite the modified death sentence. Incidentally the Black Cap remains part of a judge’s ceremonial regalia even today.

Previously, the judge would have recited a long, drawn-out set script which usually did little to help a prisoner keep their composure. It was this:

“Prisoner at the Bar, you have been convicted of the crime of wilful murder. The sentence of this Court is that you be taken from this place to a lawful prison, and thence to a place of execution where you shall be hanged by the neck until you are dead. And that your body be afterwards cut down and buried within the precincts of the prison in which you were last confined before execution. And may the Lord have mercy upon your soul. Remove the prisoner…”

Ashworth’s version was edited for brevity and out of compassion for the prisoners hearing it:

‘”Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans, you have been convicted of murder and shall suffer the sentence prescribed by law.”

Shorter, certainly. Any sweeter? Probably not. Their one mandatory appeal was heard by Lord Chief Justice Parker, Justice Winn and Justice Widgery on July 20, 1964. It was denied the next day. The executioners were engaged and a date set. Evans and Allen would die at HMP Strangeways and HMP Walton respectively. Harry Allen and Harry Robinson would execute Evans, Robert Leslie Stewart and Royston Rickard would execute Allen. Both men dying at the same time meant that no one hangman could ever claim to Britain’s last executioner.

Their final destination: The standard British gallows, never to be used again.

At 8am on August 13, 1964 Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans, quickly and without incident, passed through the gallows trapdoors and into penal history. With them went the hangmen themselves, never to be called upon again. So also went centuries of State-sanctioned killings ranging from the deliberately-barbaric to the scientifically-precise. Britain’s hangmen had reached the end of their rope.

Execution for murder was finally abolished in 1969 after a five-year moratorium on hangings. It remained for several civilian and military crimes until 1998 when it was finally outlawed under the European Human Rights Act of that year. Of assistant executioners Royston Rickard and Harry Robinson we know almost nothing. Perhaps they preferred to slip into anonymity as did Robert Leslie Stewart who emigrated to South Africa.

Harry Allen found obscurity a little more difficult to achieve. He had to move at least once to escape the publicity of being incorrectly-labelled ‘Britain’s Last Hangman’ and died in 1992, one month after his friend, colleague and mentor Albert Pierrepoint.

3 responses to “On This Day in 1964 – The Last Executions In Britain.”

-

Just to point out that death sentences were still pronounced in Britain as late as November 1965 (before suspension and – four years later – final abolition of the death penalty in Britain) and that – in the Isle of Man – a judge could still sentence a murderer to death as late as 1992 (although the Isle of Man last executed a murderer in 1872). Oh and Allen and Evans were not the last to be executed on ‘British soil’ as it were – two executions were to take place in Bermuda in 1977.

-

There should still be hangings in this country,.. it’s the only true deterrent for murder,… And it’s not barbaric,… It’s justice,..

-

it’s an eye for an eye.

Leave a Reply