Your cart is currently empty!

On This Day in 1890; William Kemmler – The World’s First Legal Electrocution.

August 6, 1890 saw the dawn of a new age for criminal history. At Auburn Prison in upstate New York there was the execution.of one William Kemmler, condemned for murdering girlfriend Matilda Ziegler with a hatchet. There was nothing remarkable about Kemmler (an alcoholic vegetable hawker with a vicious temper) or about his crime. There…

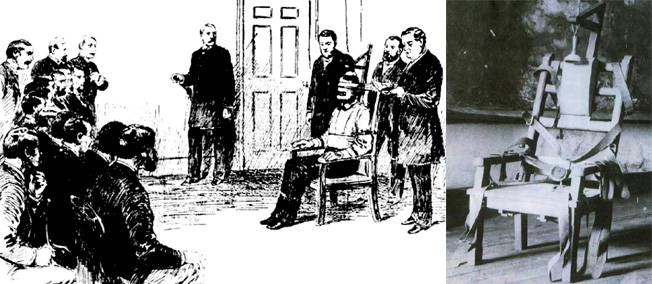

William Kemmler and the world’s first electric chair.

August 6, 1890 saw the dawn of a new age for criminal history. At Auburn Prison in upstate New York there was the execution.of one William Kemmler, condemned for murdering girlfriend Matilda Ziegler with a hatchet. There was nothing remarkable about Kemmler (an alcoholic vegetable hawker with a vicious temper) or about his crime. There wasn’t anything unusual about an execution in New York State, either., hangings being a fairly regular event.

Matilda ‘Tillie’ Ziegler, Kemmler’s girlfriend and victim.

What was unusual was the method. Americans had been hanged, shot, drowned and burned at various times, but none had ever been electrocuted. Even the word ‘electrocute’ was brand new, a buzzword for what enthusiasts had clumsily named ‘electrical execution.’ It had never been done before. After its nightmarish debut, there was much debate about whether it should ever be done again.

Of course, it was. There have been over 4000 electrocutions in American penal history since Kemmler’s. Today ‘Old Sparky’ is (rather ironically) at death’s door, replaced by the gas chamber and lethal injection. It was once by far the most popular means for America’s prisons to perform human pest control.

State after State threw away its gallows and plugged into this new innovation. They did so with varying degrees of enthusiasm. New York loved it. South Dakota used it only once. Other States varied between the enthusiastic Florida and the far less enthusiastic New Mexico. They also turned on to the new idea with varying degrees of competence (often with hideous results for all concerned, especially the condemned).

Hanging can be the least inhumane method of execution if properly performed, so there’s a bitter irony in the reason for Old Sparky’s long tenure. Which was that many American executioners would probably have found it a challenge correctly hanging curtains, let alone humans. Bungled hangings were regular events, with prisoners often beheaded or slowly strangled by bungling hangmen using faulty or unsuitable equipment.

British hangman Albert Pierrepoint was openly scathing of American hangmen and their kit, sarcastically calling the traditional hangman’s knot a ‘cowboy’s coil.’ After one horror show too many at the hanging of Roxalana Druse, New York State Governor David Hill decided to form a ‘Death Commission’ to decide which method would best replace the rope. Enter two very big names, an inventor, a dentist and, of course, William Kemmler.

The idea of electrocution came from a dentist, Alfred Southwick of Buffalo, New York. Southwick had seen a drunk die instantly from accidentally staggering up against an electrical generator. Being a staunch supporter of capital punishment, Southwick decided that the new technology would be perfect for deliberately killing people as well. Being a dentist, he thought a chair with restraining straps was the best way to convey the current to the inmate. He left the actual building of the ‘hot seat’ to Harold Brown, an electrical engineer working for a rather famous name. Enter one Thomas Edison.

Edison had been approached to oversee the creation of the electric chair but, being firmly opposed to capital punishment, had firmly refused to take part. Unfortunately, Edison became locked in the ‘War of the Currents’ with his great rival George Westinghouse. Edison championed direct current (DC) while Westinghouse was marketing an alternating current (AC) system.

Both wanted to corner the rapidly-snowballing market in electricity and related products. Westinghouse’s system was far more efficient at transmitting electricity over long distances, but required far higher voltages to do so, making it potentially far more dangerous to technical staff and consumers.

Edison saw that as an opportunity to bury Westinghouse’s new system and corner the burgeoning electrical market for himself. Putting his personal opposition to executions aside (along with many other principles), Edison made full use of AC being more dangerous to human life.

He started a publicity campaign openly touting Westinghouse’s AC as deadly and his own DC as the safe option. A series of public demonstrations (from which Edison kept himself at arm’s length) involved- electrocuting animals ranging from cats and dogs to a fully-grown elephant. Then he reconsidered his attitude to the death penalty. What better way was there to discredit George Westinghouse by harnessing both his system and his name to death?

Westinghouse had refused to sell the State of New York a generator for executions so Brown, funded by Edison, bought one under a false name, had it delivered to Brazil and then shipped back to Auburn Prison. This infuriated Westinghouse, but not nearly as much as the more personal aspect of Edison’s campaign.

The new method, in the eyes of many Americans, needed a new name. ‘Electrocution’, a combinations of ‘electricity’ and ‘execution’ caught on to replace the clumsy phrase ‘electrical execution.’ Edison quietly tried to introduce another name. If Edison had his way, inmates would be ‘Westinghoused.’

Westinghouse was unsurprisingly outraged. This wasn’t just Edison trying to ruin his business, but trying in a particularly personal and extremely unpleasant way. Before theirs had been a business and corporate rivalry. Now it developed into a full-fledged personal feud. The bitterness between these industrial titans was extreme and William Kemmler was caught right in the middle of it.

With Kemmler, a violent drunkard, securely if not comfortably ensconced on Auburn’s Death Row, Westinghouse, for reasons business and now personal, delayed things as much as possibly by funding Kemmler’s appeals. Edison in turn secured large funding from one of his investors, J.P Morgan no less, to ensure Kemmler’s appeals failed. They did.

William Kemmler was destined to take a prime (and unwilling) place in criminal history; the first inmate ever to do the ‘hot squat.’ At Auburn Prison preparations went ahead. Harold Brown enlisted one Edwin Davis to help perfect the final touches to the ‘electrocution chair.’ Davis was a qualified electrical contractor at Auburn and was also the perfect choice to become the world’s first ‘State Electrician.’

In time Davis would execute around 200 inmates and train two of his proteges, John Hurlburt and Robert Elliott. Both of whom succeeded him as executioners. Between them, these three men would execute over 700 prisoners. Elliott would be credited with perfecting electrocution as an execution method, developing what became known as the ‘Elliott Technique’ or ‘Elliott Method.’ Even today when electric chairs work on an automatic, pre-set programme, it’s based on Elliott’s earlier manual method

For now, though, Davis was in charge. Davis designed and patented the first electrodes which on early chairs were fixed to the inmate’s head and the base of their spine. After much gruesome experimentation and numerous hideous deaths, electrodes were later fixed to an inmate’s head and leg as standard. But that was in the future. For now, nobody really knew what they were about to be doing. On execution day this would become abundantly, horrifically obvious.

August 6, 1890 dawned bright and clear. The chair had been installed, linked to the prison generator (later chairs had their own separate generator) and thoroughly tested. Warden Charles Durston woke Kemmler at 5am, gave him a final breakfast and had him dressed for the occasion. At 6:30am the grim ritual began. Kemmler, his head and spine shaved and with a slit in his shirt-tails, was led into a room in front of 17 witnesses including 3 doctors and numerous reporters. He was asked for his last words which proved grimly ironic in the light of what was about to happen:

“Take it easy and do it properly, I’m in no hurry…”

Kemmler probably would have been in a hurry if he’d known what was coming. The execution team, given that they’d never actually electrocuted anyone before, certainly didn’t do it properly. About the best that could be said for the witnesses was that their misery would be less horrendous than Kemmler’s.

The grim facade of Auburn Prison in upstate New York, the prison is still in use, but New York repealed the death penalty in 1965. The last execution in New York was in August, 1963.

At 6:38am the signal was given and Davis threw the switch. 1000 volts of alternating current seared through Kemmler’s body and nervous system. After 17 seconds the power was shut off. Doctor Charles Spitzka stepped forward fully expecting to certify Kemmler dead.

He wasn’t.

Spitzka initially thought Kemmler was dead and said as much. The chair’s inventor, dentist Alfred Southwick, proudly stood before the witnesses. In front of Kemmler’s smoking body Southwick uttered the immortal words:

“Gentlemen, we live in a higher civilisation from this day.”

So, briefly, did William Kemmler who began breathing and started twisting against the straps while moaning increasingly loudly. Horrified witnesses blanched as Warden Durston and Doctor Spitzka hurriedly discussed what to do. Either the current had been too low or not applied for long enough. The obvious solution, naturally was to double the voltage and increase the duration. Spitzka spoke briefly and sharply:

“Have the current turned on again, quick. No delay!”

The current was turned on quick. It was also set far too high for far too long. For a full minute 2000 volts cooked Kemmler alive. His remaining hair smouldered. His flesh singed. Blood vessels burst under his skin causing him to bleed through his pores. Smoke and a stench of burnt meat filled the room while witnesses tried to get out and pounded on locked doors. Several fainted.and slumped around the floor.

Kemmler did at least die, but in a way that nearly made his both the first and last electrocution in criminal history. Newspapers competed to run the gaudiest, grisliest tales of his suffering, as though it needed to look any worse than it already was. Two of the doctors present, Charles Spitzka and Carlos MacDonald, feuded bitterly and publicly for years afterward over what had gone so dreadfully wrong.

Edison, whose role in the affair was now public knowledge to his lasting discomfort, refused to comment or to even speak to reporters. His great rival George Westinghouse, asked for his opinion of the execution, was far more forthcoming and brutally frank:

“They would have done better using an ax…”

Of course, the chair, its components and the overall method survived even into the early 21st century. Over time and by trial and error the process was steadily refined, though never really perfected. Davis’s apprentices Hurlburt and Elliott would develop the process and kill hundreds doing so, Although Hurlburt did commit suicide shortly after resigning as the euphemistically-titled ‘State Electrician.’

All of New York’s executioners had to be qualified electricians, paid $150 per prisoner with an extra $50 for any additional prisoner during multiple executions. Good money if you could stomach the work generally and the occasional botch in particular.

Tennessee’s electric chair at the Riverbend Maximum Security Institution

There’s a grim postscript to this story. Until recently Old Sparky had fallen into disfavour and disuse. No States retained it as their primary method, most having changed to lethal injection as their first choice. The current refusal by drug companies to supply American prisons with the drugs for lethal injection has led to experimentation with different drug combinations and, in turn, botched lethal injections such as Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma and Joseph Wood in Arizona. Wood took over two hours to die in a process that should have taken minutes.

Which is why the State of Tennessee, previously discarding their electric chair for lethal injection, have reinstated electrocution and dusted off their ‘hot seat.’ South Carolina is considering doing the same. Alabama and Oklahoma, meanwhile, are considering something new and as yet untried. The gas chamber too has been discarded, but it might make a comeback using nitrogen gas instead of cyanide. Oklahoma was also the first state to adopt lethal injection, although Texas was the first to actually use it.

It would seem the wheel is going to turn full circle. Like William Kemmler on this day in 1890, somebody is likely to take their own place in the chronicles of crime, albeit as the first to suffer death in a nitrogen (not cyanide) gas chamber. Unlike William Kemmler and some 4000 other inmates, Old Sparky might also be rising from the grave.

Kemmler’s tale can be found, among many others, in my first book ‘Criminal Curiosities’ available on Amazon Kindle:

8 responses to “On This Day in 1890; William Kemmler – The World’s First Legal Electrocution.”

-

Zzzzzzzzzzzzzz!

-

[…] Vermont had eight executions in the twentieth century while New York had 663 out of 605 between William Kemmler on August 6 1890 and Eddie Lee Mays on August 15 1963.. While Vermont executed eight convicts in […]

-

[…] August 6, 1890 Auburn Prison in upstate New York made history. William Kemmler, drunkard, vegetable-seller and killer, became the first prisoner to die in the electric chair. […]

-

[…] fact New York’s so-called ‘Death Commission‘ that originally recommended the electric chair as a replacement for the gallows specifically […]

-

[…] used on William Kemmler at Auburn Prison on August 6, 1890, New York originally had three chairs at Auburn, Dannemora and […]

-

[…] the problems with William Kemmler and Gee Jon that bodes ill for whoever might become an unwilling part of penal history. New York […]

-

[…] 1912 was the twenty-second anniversary of the world’s first judicial electrocution, that of William Kemmler at Auburn Prison in 1890. South Carolina’s first was William Reed, an African-American […]

-

Reblogged this on Crimescribe.

Leave a Reply to CrimeScribeCancel reply