Your cart is currently empty!

Aum Shinryko: Japan’s largest execution since World War II?

Japan, one of only two members of the G7 to retain capital punishment, the other is the US, has never liked publicity regarding its death penalty. Just as the British used to do until abolition, it’s shrouded in secrecy. Even the condemned don’t know until shortly beforehand that their time has come. The public don’t…

Japan, one of only two members of the G7 to retain capital punishment, the other is the US, has never liked publicity regarding its death penalty. Just as the British used to do until abolition, it’s shrouded in secrecy.

Even the condemned don’t know until shortly beforehand that their time has come. The public don’t know until after they’ve died and an official announcement is made. Until then, the condemned, the execution process and especially those who carry it out are hidden away, out of sight if not of mind.

Today’s mass execution has changed all that.

This morning Japan performed what is probably its largest mass execution since the war crimes trials after World War II. Seven members of the Aum Shinryko cult responsible for the Tokyo subway attack on March 20, 1995 were escorted from their cells one by one and dropped through the trapdoor at a Tokyo prison.

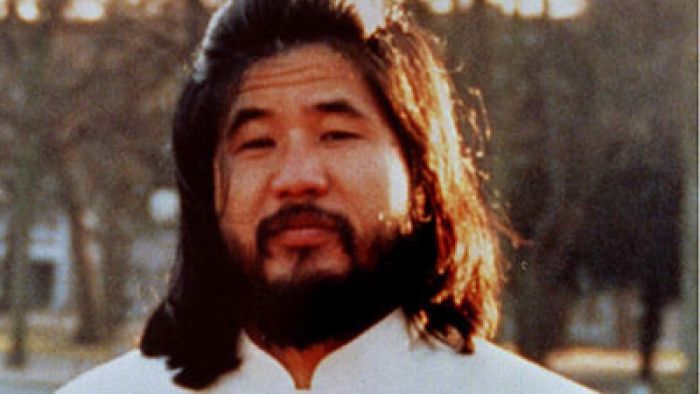

One after another cult leader Shoko Asihara, Yoshihiro Inoue, Tomomitsu Niimi, Tomomasa Nakagawa, Kiyohie Hayakawa, Seiichi Endo and Masachi Tsuchiya were taken from their cells to the trapdoor, strapped, hooded, noosed and dropped. Three prison officials pushed three buttons, only one of which released the trapdoor. Six more cult members are still awaiting the same fate.

Many, Japanese or not, would say it was justified. They’d littered Tokyo’s subway with packages of nerve agent Sarin, killing 13 people and injuring thousands. It wasn’t their first gas attack on their fellow citizens, they’d attempted a similar Sarin attack before and would try it with cyanide gas later. Even after today’s hanging of seven of them another six still remain on death row. All told, not prisoners likely to attract much, if any sympathy.

Japan has long tried to keep its executions as secret as possible. Unlike the US where such criminals would attract more publicity than the biggest celebrities (at least around their executions), the Japanese like to keep it as discreet as possible. With a case like this, though, discretion is impossible. The attack was too notorious, the resulting executions were simply too big to hide.

Until recently Japan’s condemned were given no warning at all. They’d simply be roused if they were asleep, told it was time to go and within hours they’d be dead. Even Britain’s condemned knew their date and time beforehand. But Japan’s stance has softened a little in recent years. In 2010 Keiko Chiba, then Minister of Justice and an opponent of capital punishment, decided to stimulate debate by granting the media their first access to the death chamber itself. Traditionally, it’s also the Justice Minister’s responsibility to sign the death warrant formally beginning the execution process.

As in the US, capital justice moves slowly. Technically a prisoner should be hanged within six months of sentencing. In practice, prisoners have remained on death row for decades between sentencing and execution while appeals are heard, sometimes granted and often dismissed. Once the Justice Minister puts pen to paper, however, it moves far more quickly.

For the remaining six cultists and the hundred or so other condemned inmates, every day could be their last. They just don’t know which day it will be.

Leave a Reply