Your cart is currently empty!

On this Day in 1925; The Biter (nearly) Bitten at Sing Sing.

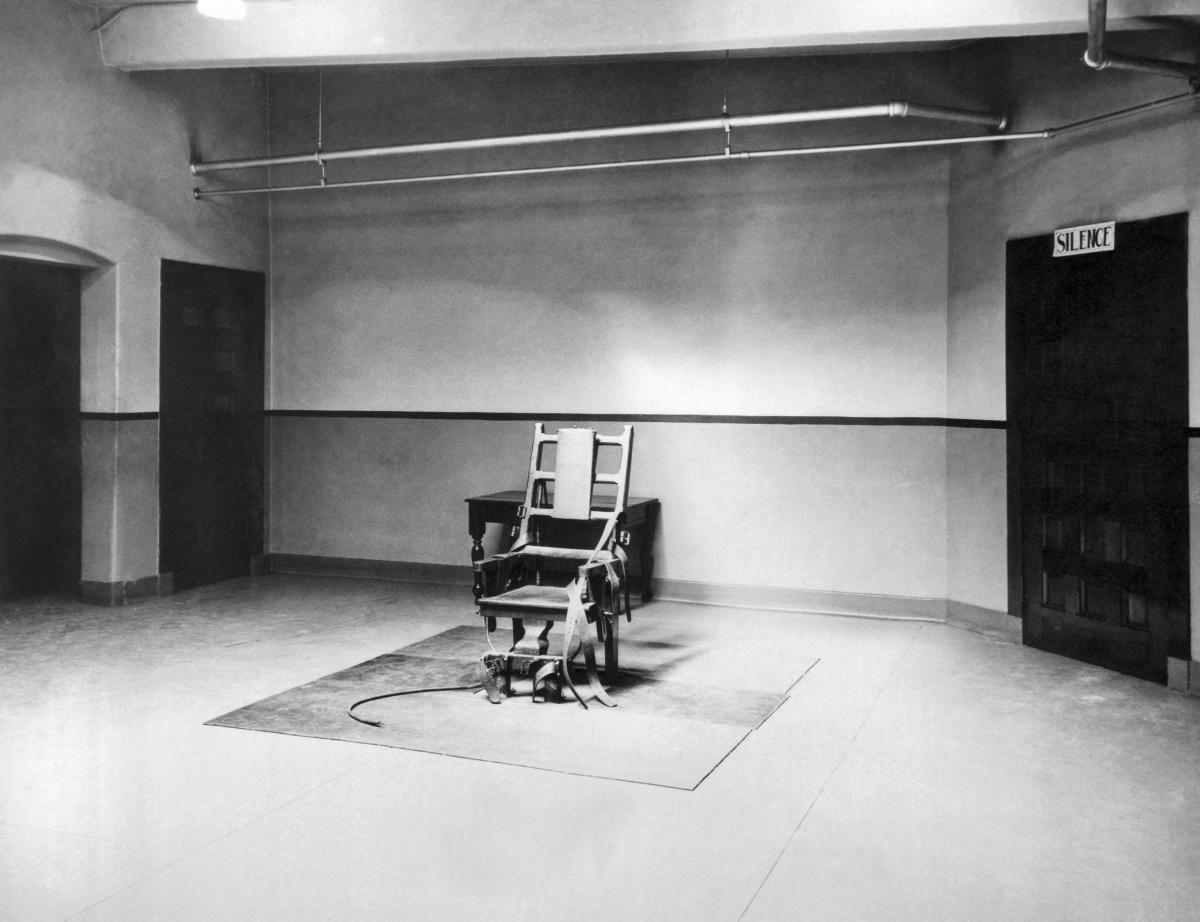

When heroin-loving gangsters Morris ‘Whitey’ Diamond and his brother Joey teamed up with John Farina for an armed robbery and murder, they surely knew they had a fair chance of joining him in Sing Sing’s Death House and Old Sparky as well. The 1920’s and 30’s were halcyon days for New York’s ‘State Electrician’ and…

When heroin-loving gangsters Morris ‘Whitey’ Diamond and his brother Joey teamed up with John Farina for an armed robbery and murder, they surely knew they had a fair chance of joining him in Sing Sing’s Death House and Old Sparky as well. The 1920’s and 30’s were halcyon days for New York’s ‘State Electrician’ and his infamous contraption, after all.

What they would never live to know (and executioner John Hurlburt came to know all too well) was that Hurlburt very nearly joined them in Sing Sing’s morgue. Hurlburt’s story is no great secret (you can find my account of it here) but less is reported of the night he found himself almost as dead as any of his 140 ‘customers.’

The Diamonds and Farina found themselves awaiting death for an armed robbery committed in 1924. They stole over $43,000 from bank messenger William Barlow and guard William McLaughlin. In the process they shot Barlow (a retired NYPD officer) three times in the back. McLaughlin (a US Army veteran) managed to fire a few shots before dying.

It might have gone better if the Diamonds hadn’t been using heroin before the job. It might have gone better still if Whitey hadn’t left a blood-stained finger print in the getaway car, hadn’t left a false licence plate where it was easily found and hadn’t falsely registered it under the name ‘Joe Samuels.’ It probably didn’t help that the address on the false registration was also where Whitey habitually collected his mail.

Further bad news came via bank clerk Antony Pantano, the gang’s inside man. For a lowly clerk, his colleagues thought, he had an unusual interest in the bank’s security \arrangements, especially those involving cash deliveries and collections. When their colleagues were ambushed and left dying in the street, they immediately pointed the finger at Pantano.

Grilled by NYPD officers furious at Barlow’s murder and no doubt wanting to avoid a seat in Old Sparky, Pantano cracked. He named the Diamonds and Farina as the shooters and Nicky ‘Cheeks’ Luciano and George Desaro as driving the two getaway cars. Luciano, no relation, takes no great role in the story. Desaro was later arrested in his native Italy, which agreed to prosecute him and gave him 30 years for his role. He was luckier than Farina and the Diamonds, but not Pantano.

Pantano also found himself going ‘up the river’ to await ‘Black Thursday,’ but his sentence was commuted. Those of the Diamonds and Farina, however, weren’t. New York’s courts had an unwritten rule of never interfering in the cases of condemned cop killers and that Barlow had been retired made no difference. The Whitey, Joey and Farina would die on the same night, April 30, 1925, one after another.

New York’s death warrants only specified a particular week for a prisoner’s electrocution. With that in mind, executions were traditionally conducted on Thursdays (barring last-minute legal appeals, stays of execution, temporary reprieves or commutations.

As Pantano left the Death House for Sing Sing’s general population, it must have occurred to him that he’d had a very narrow escape. During its tenure, Sing Sing’s Old Sparky (New York once had three of them) claimed 614 of the State’s 695 electrocutions. For every three inmates who walked in, two were wheeled out.

New York wasn’t a State noted for its generosity to the condemned. Pantano’s information and his being a first offender had undoubtedly saved him. As career criminals the Diamond brothers and Farina knew the rules of the game. They must also have known they’d gambled their lives, and lost. John Hurlburt pencilled a lucrative date in his diary, as much as he’d come to hate the work.

Hurlburt’s contract with New York was the same as his predecessor Edwin Davis. For single executions he was paid $150 and travel expenses. For doubles or more, which weren’t unusual, he got $150 for the first inmate and an extra per head thereafter. He would leave Sing Sing with $250 for his night’s work, more than some people earned in a year. Hurlburt, however, was cracking up.

Hurlburt had taken over from Davis when Davis retired in 1912, Davis having trained both Hurlburt and another assistant, Robert Greene Elliott. Initially a believer in capital punishment, he now found himself doing the job only for the money. With his wife Mattie chronically-ill he had no other way to pay the medical bills.

In the months before his date with Farina and the Diamonds he’d become withdrawn, sullen, temperamental, aggressive and depressed. Tantrums were regular, Hurlburt throwing items of equipment around the death chamber and cursing at guards while preparing for an execution.

This time, hours before he was due to earn his fee, Hurlburt suffered a nervous collapse. Prison officials were facing a crisis. Under New York law only a State Electrician could perform an electrocution and Hurlburt was the only one they had. No electrician, no electrocution. After much soft-soaping, gentle persuasion and cajoling, Hurlburt recovered enough to do the job, but only just.

At 11pm, Morris was first in line. He walked in, sat down and died. As his body was wheeled away in came his brother Joey. When Joey had been pronounced dead John Farina rounded out Hurlburt’s triple-hitter. Hurlburt, a broken man by then, promptly suffered another nervous collapse. He spent the next week in hospital before recovering enough to leave. Unfortunately for Hurlburt, who desperately needed relaxing, calm and above all safe surroundings, he was taken to the nearest available medical facility;

The infirmary at Sing Sing Prison.

Luckily for Hurlburt, he’d been a firm adherent to Edwin Davis’s approach to anonymity. The press had his name, but they never got a picture or any other personal details. His desire for anonymity and the safety thereof was about to save his life.

Some people just aren’t popular in prisons. Informers, ex-cops, ex-guards and sex offenders usually top the list of people considered fair game. Anyone wanting to make them suffer and possibly kill them has virtually free rein to do so if they can get away with it. Seldom, however, will you find anyone convicts hate more than an executioner.

Hurlburt must have been terrified. He couldn’t have avoided the fact (and fear) that, if anyone blew his cover, Hurlburt would be a dead man. He’d immediately be headed for the same morgue as the 140 or so inmates on whom he’d inflicted the ‘hot seat.’ If they even thought he might have been involved with Old Sparky, they’d kill him.

All in all, not what the doctor ordered. With the Diamonds and Farina dead, Hurlburt himself didn’t last much longer. He performed only two more executions, John Durkin on August 27 and Julius Miller on September 19, then resigned only hours before he was due to executed John Slattery and Ambrose Miller. on January 16, 1926. Slattery and Miller were delighted, their executions were postponed and subsequent legal action saw them commuted. Their accomplices Luigi Rapito and Emil Klatt were less fortunate.

By their date on January 29 New York had appointed the other of Davis’s two proteges, the legendary ‘Agent of Death’ Robert Greene Elliott. Another accomplice, Frank Daley, followed them on June 24. Daley played it tough until the bitter end, cursing Slattery and Ross for implicating him until the switch was thrown.

As it turned out Hurlburt, in failing health himself, his nerves broken and grieving after Mattie’s death in September, 1928, wasn’t long in joining them. On the afternoon of February 22, 1929 he walked into the basement of his home near Auburn Prison where he’d worked as both electrician and performed his very first executions. In his hand was the revolver he always carried when visiting a prison.

He didn’t walk out.

5 responses to “On this Day in 1925; The Biter (nearly) Bitten at Sing Sing.”

-

[…] Surrounded by convicts, some of whose friends and relatives had died at his hand, Hurlburt was under no illusions about what would happen if his fellow-patients knew the man they called the ‘burner’ was within stabbing distance. If recognised he would never have left the prison alive and probably died very unpleasantly. Not for nothing did the prison’s general population crow whenever a reprieve or commutation was granted, remarking cheerfully that “The burner is out of a fee.” […]

-

Hi Robert! I came across this post while researching family history. I’d love to get in contact ask about some of the sources for the details you’ve included here about Morris and Joseph Diamond.

-

Ah the Diaond brothers. I’ll dig through my files and send you what I can find.

-

That would be so great! Thank you.

-

-

-

Hello Robert,

I would like to know any further information you may have of the Diamond Brother. Morris was my paternal grandfather and Joe was my great uncle. The execution of their brothers became a family secret . It was kept until before my father died. I also have no information of my maternal grandmother who died before the robbery.

I recently came across a very old picture of the brothers standing in front of a car. It is a very sad memory not only for my family but for all they harmed.

I have read the NYTimes court coverage and was very close to my great Aunt Sally who fought bravely for her brothers. I believe my father was present in court during the trial.

I would appreciate any assistance you may have.

Thank you in advance for your assistance.

Jo DavidsonMy daughter Meghan Donnelly was also grateful for your article.

Leave a Reply