Your cart is currently empty!

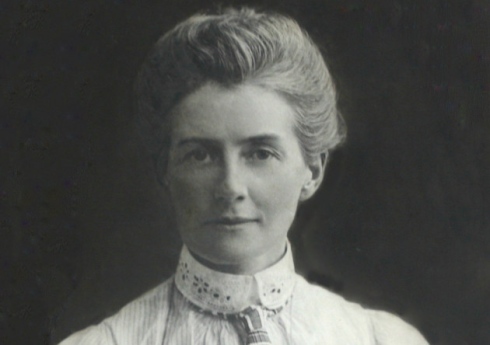

Edith Cavell – Hand-wringing propaganda is not enough. Nor does it do her any service.

“I am glad to die for my country.” – The last words of Edith Cavell. Edith Cavell was shot by a German firing squad at the Tir National rifle range near Brussels on October 12, 1915, having been convicted by a German military court of aiding the enemy by helping Allied soldiers and escaped prisoners…

“I am glad to die for my country.” – The last words of Edith Cavell.

Edith Cavell was shot by a German firing squad at the Tir National rifle range near Brussels on October 12, 1915, having been convicted by a German military court of aiding the enemy by helping Allied soldiers and escaped prisoners through Belgium into neutral Holland. Her death brought international condemnation for Germany, aided to the maximum by British propaganda seeking to take full advantage of her death. But, despite their publicly-stated desire to see her reprieved, how much could the British have done to save her? Did they do all they could? And, as a martyr to the British cause, was Edith Cavell worth more to them dead than alive?

The British propaganda machine certainly exploited her execution to the absolute maximum. Published accounts of her death range from the mildly-exaggerated to the blatantly dishonest and don’t tend to coincide with the eyewitness accounts of those whose grim task it was to actually watch her die. One then-popular account states that she completely lost her nerve at her execution and, far from facing her death in the stereotypically heroic fashion, fainted. Having fainted, according to this rather creative version of events, the officer in charge simply walked over to her prone figure and calmly shot her in the head with his service pistol.

Looking at it from a propaganda perspective, Edith Cavell was worth more to the British dead than alive. Having already been captured her work helping escaping Allied soldiers was over so her purpose as an active agent was already served. Even if she had been reprieved which, with bitter irony, would have aided the German cause far more than that of the British, she would certainly have spent the rest of the war in prison and thus of no further value to the British. After being shot, on the other hand, she became a far more damaging British weapon than running an escape line. She became a martyr instead.

The facts of the case were fairly straightforward. Cavell admitted under questioning that she’d helped over 200 Allied fugitives escape through Belgium into neutral Holland. She was proved to have given them shelter and supplied them with food, money and false identity papers to help them across the border. In short, she admitted committing capital crimes under German military law at the time, and it was under German military law that she was tried, convicted and condemned.

Whether or not she at any time involved herself with active espionage as well is debatable. Noted espionage expert Nigel West is positive that she did and that she did so knowing the risks if she was caught. M.R.D Foot, a distinguished military historian and former intelligence officer who also served with the SAS during the Normandy campaign, is absolutely positive that Cavell was originally engaged by the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) to assist with a spy ring, but turned her back on espionage to instead assist Allied fugitives. Beyond West and Foot’s accounts, however, there’s so far no evidence that she engaged in active espionage. According to archive evidence studied by former MI5 Director Dame Stella Rimington, Cavell knew at least something about information being passed back to England via her network.

It would have made no difference anyway as she was never tried for espionage, but for aiding the enemy and neither Cavell nor the British ever denied that she did do so.

Another, rather distasteful, speculation concerns her brief time under a death sentence. The British don’t seem to have done all that much to save her. but what could they have done? That she was guilty is undoubted and the Germans were hardly likely to grant any clemency request coming from the British, especially as the British shot eleven prisoners during the First World War convicted of espionage on behalf of the Germans. It does seem as though, in the absence of any meaningful options to stop her execution, British propagandists made the best use possible of an execution their superiors could do little or nothing to prevent.

Cavell herself seems to have made much less fuss about her death than propagandists did. According to Chaplain Gahan (who made a final visit hours before her execution) she was calm, rational and accepted her fate with great dignity and fortitude (far from the image of the prostrate victim callously finished off with an officer’s service pistol as she lay catatonic on the Tir National rifle range). She went to her death composed and calm, not collapsed on the ground before her executioners. She even refused a blindfold, which hardly suggests she was unable to face her final ordeal.

There isn’t any evidence to suggest that Edith Cavell’s death was actively connived at by the British authorities. The evidence for her actively involving herself in espionage is equally debatable. But what can’t be denied is that she knew what she was doing, she knew the likely outcome if she were caught and yet she chose to do it anyway and take the risk. She gambled her life for her principles, and lost. What’s also undeniable is that, not having prevented her death, British propagandists made as big a meal of it as they possibly could. Granted, that isn’t the same as doing less than they could have to secure clemency, but it’s still thoroughly distasteful and opportunistic on a grand scale.

The German authorities, themselves conflicted about executing her, finally decided to make an example of her via the firing squad. Like the British authorities after the 1916 Easter Rising, they did make an example of Edith Cavell. Unfortunately for both governments it was seen by many as an example of their own cruelty and callousness and they couldn’t have handed their opponents a bigger propaganda victory. Instead of setting examples to avoid, they set examples to follow.

What we’d nowadays call sexism also played its part. The Germans were keen to show that being female wasn’t an ‘get out of jail free’ card for condemned prisoners. British propagandists were equally keen to exploit her gender. whining bitterly about how barbarous it was to execute a woman. Bitter irony when you consider that British women were routinely hanged for murder at the time. False reports of her collapse before the firing squad, the suggestion that she should be reprieved simply on account of her gender and the general idea that shooting a woman for aiding the enemy was an atrocity while no similar degree of attention would have been lavished on a man condemned for exactly the same acts do her memory no favours.

Was she the proverbial ‘Weak and feeble woman’? No.

Did she know what she was doing and the penalty if she were caught? Yes.

Was she also at any point actively spying as well as helping Allied fugitives into neutral territory (and then on to Britain to continue fighting the Germans)? Maybe.

Edith Cavell was a brave person who made freely the choice to risk her life. She did so knowingly. She faced her end as bravely as any man, not as some hysterical banshee unable to face the consequences of her actions. German authorities at the time may have done themselves a disservice by not commuting her sentence, but British propagandists have done far worse to her memory and her place in history.

One response to “Edith Cavell – Hand-wringing propaganda is not enough. Nor does it do her any service.”

-

Reblogged this on Crime Scribe.

Leave a Reply