Your cart is currently empty!

Professor Ross Marvin – Murder At The North Pole..?

Well, we’ll problably never know and that’s what makes this case so interesting. A distinguished Professor, two Inuit helpers, the first successful expedition to the North Pole and Admiral Robert Peary, one of America’s most famous explorers. Throw in the frozen wasteland of the Arctic Circle and that the murder (if it was a murder)…

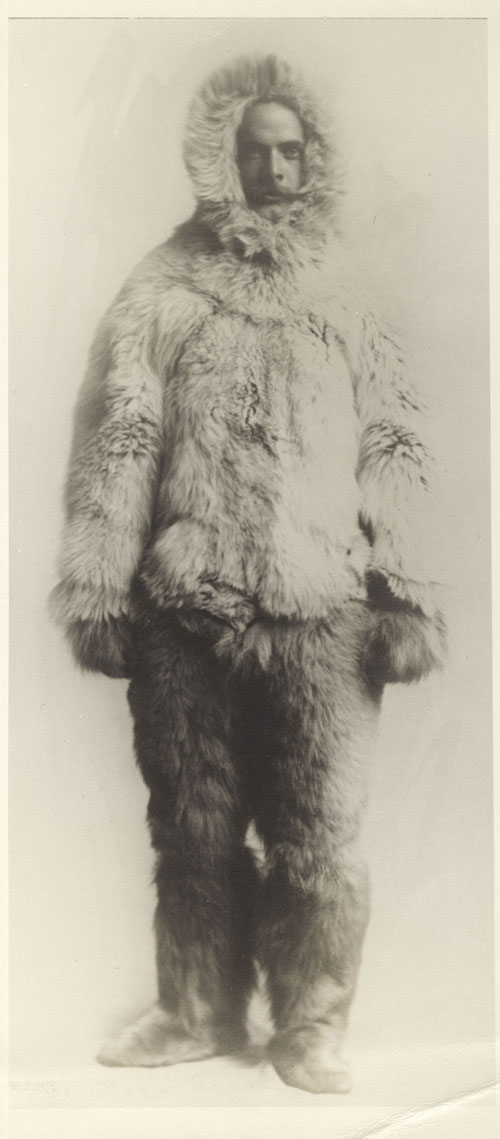

Ross Marvin, one of history’s more unusual murder victims..?

Well, we’ll problably never know and that’s what makes this case so interesting. A distinguished Professor, two Inuit helpers, the first successful expedition to the North Pole and Admiral Robert Peary, one of America’s most famous explorers. Throw in the frozen wasteland of the Arctic Circle and that the murder (if it was a murder) occurred in an area not within any legal jurisdiction and you end up with more questions than answers. What really happened? Did Marvin go insane under the strains of Polar exploration? Did his Inuit helpers have to kill him to save themselves? Was it a murder or simply self-defence?

Our tale begins in 1908, when Admiral Peary led his eighth attempt to reach the North Pole. In late-1908 the party left for Greenland with Peary in command and Marvin acting as his personal secretary and in charge of training the team in basic survival techniques such as sledge maintenance and repair and how best to build shelters. Marvin was a resolute, determined and brave soul, physically fit and highly educated with degrees in physics and meteorology as well as being a qualified civil engineer. He was the type who actively sought out challenging, hazardous environments. Peary,himself no shrinking violet, took a liking to Marvin immediately and also saw his valuable skills.

Admiral Peary, leader of the 1908 Polar expedition.

Peary broke his team up into seven small parties. In total there would be 28 sledges pulled by 148 huskies and the party would be accompanied by 19 Inuit helpers. Two of these would find themselves taking a very rare place in criminal history. Six groups were to support Peary’s team in their attempt to reach the North Pole. They would travel by different routes, each dropping off supply caches as they went for Peary’s team to collect as they moved towards their destination. Between September, 1908 and February, 1909 they trained hard for the mission and departed as soon as conditions made an attempt feasible. Marvin and two Inuits, Kudlooktoo and Inukitsoq, made up the sixth of the seven groups which departed. Inukitsoq and Kudlooktoo would return. Marvin would never be seen or heard of again.

But what exactly happened? Peary’s team reached the North Pole on April 6, 1090 and sent a message on their return from the Pole dated September 6, 1909:

‘Stars and Stripes nailed to the North Pole – Peary.’

Initially, the two Inuit helpers arrived at the rendezvous site where Peary’s men were celebrating their success. Peary’s sense of achievement and glory was thoroughly ruined by their report that Marvin had fallen through a patch of thin ice and, unable to rescue him, they had to leave him where he was and return to the rendezvous without him. As Peary put it:

“It killed all joy I had felt. It was indeed a bitter blow to our success.”

The expedition erected a memorial to their fallen member, reading:

‘In memory of Ross Marvin of Cornell University. Aged 34. Drowned April 10, 1909, fifty-five miles off Cape Columbia, returning from 86 degrees 38 minutes northern latitude.’

It would be seventeen years before the truth (or a well-concocted lie) would come out. Danish missionary Jens Olsen was preaching at Karnah in 1926 and his prayer meetings were well-attended. One of them saw Inuksutoq and Kudlooktoo attend and, when Olsen asked if anybody in the crowd wanted to confess their sins, Kudlooktoo stunned all concerned by standing up and saying:

“Ross Marvin did not die because he drowned, but because I shot him.”

According to the two Inuits, Marvin’s personality had become progressively more irrational and disturbed as the expedition wore on. He became increasingly foul-tempered, aggressive, verbally abusive and his behaviour deteriorated to the point where he emptied Inukutsoq’s possessions from the sled and attempted to leave him out on the Arctic tundra with no way to get back to the start point which would have meant certain death. One of them stated:

“It was not at all our good Marvin. He was a different man from the one we had come to know.”

Having tried to ditch one of his helpers, Marvin proceeded on with Kudlooktoo in tow and they were caught up by Inukutsoq and they stopped to rest. Marvin also refused to allow Kudlooktoo to share his igloo, which would almost certainly have been fatal., before telling him that he would also not have any food. During questioning by Danish explorer Knud Rasmussen, Kudlooktoo said he’d asked for his rifle to shoot a seal and instead shot his employer before turning the gun on his fellow Inuit and threatening him with summary execution if he informed anybody of what Kudlooktoo had done. Both men, fearing ‘white man’s justice’, had managed to keep silent for seventeen years before one of them felt a need to unburden himself.

What actually happened is unclear. We only have the word of the two survivors as to why Marvin was killed. On the other hand, it isn’t unknown for explorers to lose their minds when confronted with extreme hardship and discomfort for extended periods. What confused things even more was that, at the time, the area wasn’t part of any legal jurisdiction. In the absence of any nationality, the area was effectively exempt from the rule of law until it was finally claimed by Denmark in 1921, some years after the killing happened. With no legal system in place at the time, there could be no trial which left the Inuits, regardless of whether they committed a cold-blooded murder or acted in self-defence, free to continue their lives without any further action being taken.

A Professor, a distinguished explorer and Admiral, two Inuits, the North Pole and a killing, certainly one of the most curious (and frustratingly odd) events in criminal history.

Leave a Reply