Your cart is currently empty!

The Strange Case Of Leroy Henry

The strange case of Leroy Henry attracts me for two reasons. One is that I like to look at the unusual. Even if posting on a widely-known and common story then I prefer one with a twist. It helps keep things interesting. Leroy Henry’s case was very interesting. Private Henry was one of the hundreds…

Leroy Henry was condemned only days before the Normandy landings began. His case was a headache Eisenhower didn’t need.

The strange case of Leroy Henry attracts me for two reasons. One is that I like to look at the unusual. Even if posting on a widely-known and common story then I prefer one with a twist. It helps keep things interesting. Leroy Henry’s case was very interesting. Private Henry was one of the hundreds of thousands of Americans who flooded the UK in preparation for Operation Overlord, the liberation of Europe.

He arrived in 1943 and was assigned to the 3914 Quartermaster Gas Supply Company delivering fuel to various US Army units. He was also black and so had to endure both the racial segregation in the Army at the time and no small amount of racial prejudice, particularly from his fellow Americans. He was based in Somerset, near Bristol and it was at Somerset’s Shepton Mallet Prison that he nearly, but not quite, kept an unjustified date with the hangman.

The summer of 1944 was, for obvious reasons, a rather busy time for Americans and their British hosts. Few people knew when or where the forthcoming invasion would happen, but it was no secret that sooner or later it would. Private Henry, like most young soldiers abroad, liked to spend his time off relaxing. A few drinks, a dance or a movie and maybe some time with a woman. There’s nothing unusual about that, or about the fact that he was apparently paying for her time.

But Leroy Henry was an African-American in a segregated US Army from a country with a long-established history of open racism. Keeping people like him in what many whites considered their place was standard practice and many whites were unfussy about how it was done. In the South lynchings still occurred, though less frequently than before. African-American defendants stood a far higher chance of conviction in the courts, especially if the alleged victim was white. If convicted of a capital crime they were much more likely to die.

Leroy Henry was African-American, came from Missouri (not the most racist state in the Union, but no sinecure either) and faced trial for the alleged rape of a 33-year old British woman. A white 33-year old British woman. Rape in the US Army was and remains a capital crime under Section 120 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). Defendants at Henry’s time would be tried for their lives under the US Army Articles of War of June 4, 1920. A black defendant, institutionally racist Army and white alleged victim meant his case didn’t look promising for the defence. It wasn’t.

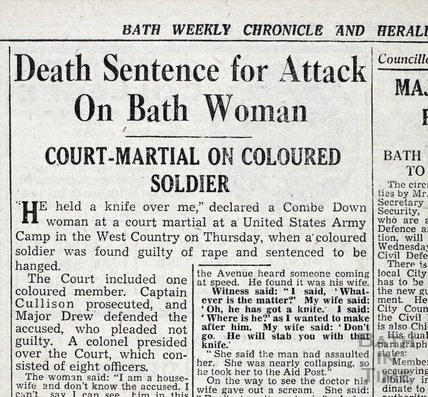

Henry was court-martialed at a US Army camp near Warminster. Under the Visiting Forces Act, Parliament had agreed that the US military could handle its own criminal cases unless they handed a case over to the British police and judiciary. They seldom did and Henry’s case wasn’t. The court-martial was presided over by a Colonel, prosecuted by a Captain Cullison and Henry was defended by a Major Drew. The jury consisted of eight officers, seven white and one black.

Henry’s alleged victim claimed he had appeared at her home in Combe Down late one night. He was lost and asking for directions to the city of Bristol. She also claimed her husband was present and that he had no objections when she offered to go out with Henry and personally direct him. Having left the house she alleged that Henry had assaulted her, threatened her with a knife, thrown her over a wall and then raped her.

There were, however, some serious doubts about her having made a genuine allegation. Inquiries revealed that she had been at least a part-time prostitute offering sex to soldiers for money, food and goods often entirely unavailable due to strict wartime rationing. That in itself doesn’t prove perjury in the slightest, but more doubts were to follow.

Chief among them being that, while medical examination revealed sexual activity, it found no trace whatsoever of physical injury, signs of a struggle or indeed any evidence of mistreatment. Inquiries also revealed that Leroy Henry and his alleged victim were known to each other and had been for some time.

Henry, not surprisingly, gave a different version of events. He admitted sleeping with the alleged victim, but claimed he had agreed to pay her for doing so. According to Henry he had been prepared to pay her £1 (worth far more then than today) but she had demanded twice that. According to Henry, he told her he didn’t have £2 and was prepared to pay half, at, she flew into a rage and threatened to report him for raping her.

So the jury had two different stories. One came from a black defendant without any supporting eyewitnesses who may or may not have been lying to save himself. The other came from a white woman whose character would have been considered dubious by the standards of the time and who claimed to have suffered a violent attack with no physical injuries. The jury chose to believe the alleged victim.

Private Leroy Henry was found guilty and condemned to death by hanging. The sentence was to be carried out using a standard British gallows operated by British executioners. Henry was shipped to Shepton Mallet (a British civilian prison loaned to the US Army for the duration).

147 US servicemen were executed for crimes committed during the Second World War, 70 of whom died in Europe. All were convicted of rape and/or murder. All were either hanged or shot, shooting being preferred for purely military offences (desertion or mutiny) with the exception of the US Army’s sole execution for desertion during World War II, Private Eddie Slovik.

Having been convicted of a capital crime involving a civilian, Leroy Henry would hang unless a Board of Review rejected the sentence or a General commuted it. Under the circumstances neither a sympathetic Board of Review or equally sympathetic General were especially likely.

The then-new gallows chamber at Shepton Mallet Prison. Leroy Henry was lucky to avoid his date with the hangman.

Shepton Mallet had become the US Army’s princpal military prison for the ‘European Theater of Operations’ (ETO). It wasn’t the only place in Europe where American soldiers were condemned and executed, but it was one of the more regular spots for either a firing squad or a hanging.

At Shepton Mallet firing squads were conducted at 8am. There were two prisoners shot at dawn, Alex Miranda and Benjamin Pyegate. Sixteen were hanged in the newly-constructed gallows room built to British specifications and operated by British hangmen. Under English law only executioners on the Prison Commissioners’ ‘Official List’ could perform hangings in British prisons, although the Visiting Forces Act did permit the US military to pass death sentences. Although the US military did have its own hangmen they couldn’t be employed. British hangmen being unfamiliar with American gallows, they requested their usual design be installed to make their job easier. An extension was duly built, attached to end of one of the cell-blocks. Hangings were usually performed at 1am.

Of those hanged, nine had been convicted of murder, six of rape and three of both. Six of them were executed standing side-by-side in three double hangings, a British gallows being designed to hang two inmates at once if needed. The average age of those executed was twenty-one years old. No officers were executed, only seventeen Privates and one Corporal. By far the majority of those executed were African-American or Hispanic. Few of them were white.

The principal executioner was Thomas Pierrepoint, assisted by his nephew Albert, Herbert Morris, Steve Wade and Alexander Riley. Albert did perform three himself, but Thomas pulled the lever most often.

Lodged in the specially-built ‘Condemned Cell’ at Shepton Mallet, things looked very bleak indeed, at least until the intervention of a local tradesman, a local dignitary and 33,000 local people. Jack Allen was the local baker who started the petition. Appalled by the quality of incriminating evidence (more the striking lack thereof) he began collecting signatures.

This wasn’t unusual in cases involving British condemned inmates and was seldom successful. The most important factor deciding clemency for British prisoners was the trial judge’s private recommendation, but Leroy Henry was an American convicted by a military court. Britain also hadn’t hanged anyone for rape in over a century. In Leroy Henry’s case public campaigning was successful especially when in the nearby spa town of Bath, Alderman and local Magistrate Sam Day added his voice and signature. What had resembled ‘Jim Crow Justice’ now became a political and diplomatic football.

Campaigning proceeded quickly and snowballed equally fast. Faced with a petition of 33,000 names, wide local outcry, highly-connected locals and finally the national press, General (and future President) Dwight D Eisenhower swiftly brought matters to a head. Not only did he refuse to confirm the death sentence, he also threw out the entire case. Private Leroy Henry was now free to return to his unit without a stain on his record. He did so.

It’s unusual that so high-ranking a figure would personally involve himself in a routine court-martial, or that he took such decisive action. It’s especially indicative of the pressure placed on him behind the scenes as Henry was condemned only a few days before June 6, 1944. For obvious reasons this was an extra headache on top of the D Day landings that Eisenhower really didn’t need.

8 responses to “The Strange Case Of Leroy Henry”

-

[…] post. Mr. Walsh’s home page has a trove of articles about historical executions, including another American serviceman hanged at Shepton Mallet. […]

-

I saw a documentary on this case several years ago. Apparently the black lawyers who defended Leroy Henry were so impressed with the way Britons responded to this injustice that after the war they joined the Civil Rights Movement. I was looking for their names when I came across your review. I haven’t found them yet.

-

Praise be God to all the British Civilians who ensured the innocence of Private Leroy Henry. Halleujah and Amen 🤗

Thank You. -

What happened to Leroy, and did he ever talk of his experience?

-

I don’t have anything other than his being returned to his unit, unfortunately. I wouldn’t be surprised if he kept as low a profile as possible.

-

-

[…] by former politician Michael Portillo, the episode covered Shepton Mallet Prison and the case of Leroy Henry. Shepton Mallet should be familiar to readers of Crimescribe, as should Leroy Henry who I’ve […]

-

a play was written about this and was performed at the Bristol Old Vic about 20 years ago

-

[…] details of the Leroy Henry case can be found on the website of Robert Walsh, a freelance writer based in […]

Leave a Reply to Leroy Henry, Shepton Mallet and the curious case of George Edward Smith. – Crime ScribeCancel reply