Your cart is currently empty!

Mathieu Orfila – ‘Father Of Toxicology.’

Meet Professor Mathieu Orfila, the ‘Father of Toxicology.’ He was born on April 24, 1787 on the island of Minorca and died on March 12, 1853 in Paris. He was a graduate of both Barcelona and Valencia in toxicology and chemistry and is one of the most influential, respected and overlooked figures in criminal…

Meet Professor Mathieu Orfila, the ‘Father of Toxicology.’ He was born on April 24, 1787 on the island of Minorca and died on March 12, 1853 in Paris. He was a graduate of both Barcelona and Valencia in toxicology and chemistry and is one of the most influential, respected and overlooked figures in criminal history. His ‘Treatise on Poisons’ is still regarded as one of the classic texts in criminal forensics and crime detection and his work resulted in the end of France’s infamous ‘Age of Poisons’ and, paradoxically for man devoted to saving lives, the public execution of many a murderer.

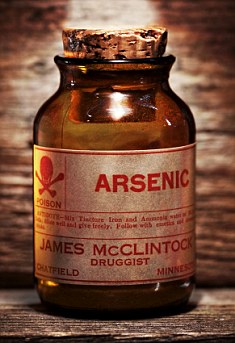

The ‘Age of Poisons’ was a poisoning epidemic within France. Toxicology and forensics were in their earliest infancy, disease was common and many poisons shared common symptoms with many poisons. Arsenic was the poisoner’s favourite, resembling the symptoms of many common diseases like gastro-enteritis, general food poisoning, dysentery and a host of others. It became so popular with murderers that it became known as the ‘Prince of Poisons’ and, in France it was delightully nicknamed ‘Poudre d’inheritance.’ ‘Inheritance powder.’

Orfila chanced upon the woefully inadequate toxicology then in use entirely by accident. In April, 1813 he was delivering a lecture on arsenic poisoning to his students and demonstrating a supposedly-infallible test to discover arsenic. The test failed despite having been properly performed and Orfila, like any academic shown up in front students, was both outraged and embarrassed. But it also made him curious. If the standard tests for so common a poison were useless, then what about tests for other poisons? After all, arsenic was the ‘Prince of Poisons’ but there were plenty of pretenders to the throne like cyanide, antimony, morphine and a whole host of others. He started running through all the commonly-used tests, checking them for accuracy and finding that a great many of them were useless even when performed perfectly well according to the instructions. He realised that, in terms of criminal detection, that most of the standard toxicology tests were useless, that many people were getting away with murder and that a fair few innocent ones were either awaiting the guillotine or had already had the ultimate haircut courtesy of what French folk called ‘The National Razor.’ Something was very, very wrong and Orfila decided he was the man to fix the problem.

He spent many months testing the tests themselves, discarding those that obviously didn’t work and improving many of those that did. The result was his famous ‘Treatise on Poisons’ published in two volumes in 1813. The ‘Treatise’ was so highly regarded that it still in publication in 1853 when Orfila died and by then had been translated into English, German, Italian and Spanish and sold well all over Europe. It was both scientifically ground-breaking and a benchmark in the beginnings of modern toxicology and forensic science. In short, it was a triumph.

Being a distinguished academic who knew the right people and had socialised with the right crowd, Orfila was able to use his contacts to push publicity and book sales. He knew scientists, politicians and lawyers at the highest level, published a second short textbook on criminal and accidental poisoning aimed firmly at laymen as much as professionals (you didn’t need to be a lawyer, detective, doctor or magistrate to understand it and, if need be, use the advice therein) and was showered with awards. In 1815 he was elected ‘Membre Correspondant’ of the Paris Academy of Science. He was awarded the ceremonial title of ‘Royal Physician’ and in 1819 was appointed Professor of Legal Medicine at the Paris Faculty. His ‘Treatise’ was also being translated into English, German, Italian, Spanish, Dutch and Portuguese and sales had skyrocketed. But it wasn’t so much his ‘Treatise’ and his social life that made his name. It was the case of Marie LaFarge in 1840, accused of poisoning her husband.

Marie was known to have bought arsenic (supposedly for rodent control), her husband had several unexplained illnesses before he died, Marie was a beneficiary when he died, had been seen putting a then-unidentified white powder in her husband’s food, white powder residue had been found in several dishes and glasses containing food consumed by her husband and prepared by Marie and, while Marie claimed to have bought the arsenic to control rats, the poison paste supposedly containing arsenic was found untouched. Analysis revealed it to contain no arsenic, but lots of flour and water and there was no evidence of there even being a rodent problem. What police and prosecutors didn’t have was proof of arsenic being in the victim’s body but, with so much circumstantial evidence available, Marie was arrested and held for trial. A conviction would mean, at best, life imprisonment. A less merciful judge might sentence her to life with hard labour (meaning a permanent stay at the French penal colonies in New Caledonia) or, most likely, she would be condemned and spend a few short weeks in the local prison awaiting her date with the ‘Man from Paris’ and his ‘National Razor.’ Things looked, very, very bleak.

The local magistrate asked the victim’s doctors, Monsieur’s De Lespinasse, Bardon and Massenat, to perform the then-new ‘Marsh Test for arsenic. The test, designed by English chemist William Marsh, was as ground-breaking as Orfila’s ‘Treatise’ and, provided it was performed 100% according to the instructions, was as near to infallible as could be. It’s still in use today, such is its reliability. The doctors knew almost nothing about the test but, rather than admit their ignorance, performed the test and submitted their results to the magistrate. According to them there was no arsenic found in Monsieur LaFarge’s stomach contents.The defence leapt on this as proof of innocence and tried to discredit the testimony of Anna Brun who had seen Marie taking white powder from a small box and putting it in her husband’s food. Having scored this extremely useful point they should have had the sense to leave well alone. They didn’t, and it would come back to haunt them and especially their client.

It was her lead counsel, Monsieur Paillet, who served the cause of justice by completely burying his own client. He insisted, in the interest of his client and to absolutely prove her innocence, that Orfila himself perform the test. As Europe’s pre-eminent toxicologist he could prove absolutely whether or not arsenic was involved. He did, and Maire LaFarge paid the price. Originally the judge decided that Orfila’s presence wasn’t required and that an affidavit from Orfila would suffice, which Orfila duly provided. The affidavit stated that the tests were so badly performed that the results were meaningless as evidence in a criminal trial which, without Monsieur Paillet’s overconfidence, should have resulted in an easy acquittal. The test itself, in Orfila’s absence, would be performed by two local chemists, Monsieur Dubois and his son, aided by Monsieur Dupuyfren, a respected chemist from Limoges. They performed the Marsh Test on the stomach contents (but not the food items retained as evidence by the prosecutor) and all agreed they had found no arsenic. Great for the defence and devastating for the prosecution. Or so it seemed at the time.

The prosecutor was a learned man who’d studied Orfila’s ‘Treatise’ extensively and knew he had only one card left to play. Arsenic can leave stomach contents over time, but lasts far longer in food items and crockery. These hadn’t yet been tested. Nor had the small malachite box that Anna Brun had testified to seeing Marie LaFarge use for storing white powder she regularly added to her late husband’s food, although the stomach contents had..It would prove to be his ace in the hole. When the defence had originally requested Orfila himself conduct the tests, the prosecutor had opposed them and the judges had backed him. Now he requested the exact opposite. Seeing as the box, food items and crockery hadn’t been tested, he argued, they now should be. And, seeing as the defence had originally requested Orfila himself do the testing, surely they’d have no objection to the prosecutor doing the same. The defence, having painted themselves into a corner and put their client at serious risk of the guillotine, had no choice but to agree.

Orfila arrived, took the food items, plates and glasses and performed the Marsh Test exactly as described in the manual. The result was entirely accurate and utterly destroyed Marie’s claims of innocence. Orfila reported, having tested everything he’d been asked to, that the food items, crockery and malachite box contained between them enough arsenic to kill dozens of people. Combined with Marie being a major beneficiary of her husband’s death, Anna Brun’s eyewitness testimony of her putting white powder in her husband’s food, his several unexplained illnesses, the fake rat poison paste that contained no arsenic and the house seemingly untouched by any actual rats, the verdict was inevitable. Marie was guilty.

The judges did show her some small mercy. She managed to avoid the guillotine, receiving instead a sentence of hard labour for life. King Louis-Phillippe also showed some mercy, albeit not much. He commuted her sentence, removing the hard labour but still leaving her imprisoned for life. She was released in June, 1852 by Ny Napoleon III (ironically the same year in which Napoleon III opened the infamous penal colonies in French Guiana now notorious as ‘Devil’s Island’). She settled in the town of Ussat, dying of tuberculosis on November 11, 1852.

Mathieu Orfila, nemesis of Marie LaFarge and so many other poisoners, died only four months later.

One response to “Mathieu Orfila – ‘Father Of Toxicology.’”

-

Who wrote this

Leave a Reply