Your cart is currently empty!

Trial Watchers – A Strange Breed.

“Prisoner at the Bar, the sentence of this court is that you be taken from this place to a lawful prison and thence to a place of execution where you shall be hanged by the neck until you are dead. And that afterwards your body shall be cut down and buried within the precincts of…

“Prisoner at the Bar, the sentence of this court is that you be taken from this place to a lawful prison and thence to a place of execution where you shall be hanged by the neck until you are dead. And that afterwards your body shall be cut down and buried within the precincts of the prison in which you were last confined before execution. And may the Lord have mercy upon your soul…”

“Remove the prisoner…”

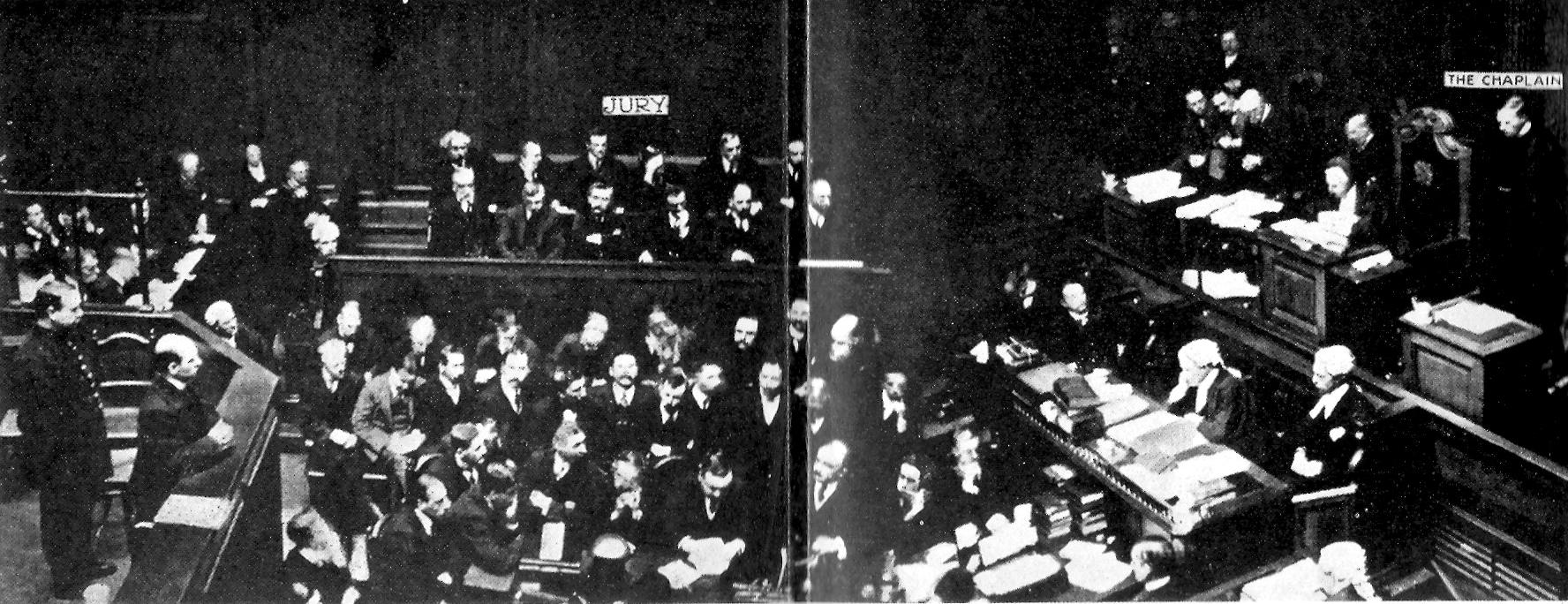

Frederick Seddon heard this sentence in 1912 and was hanged a few weeks later. Doubtless, he wasn’t happy to hear it. The trial judge, Mr. Justice Bucknill, was a kindly man by the standards of British judges. He had no relish for passing death sentences, unlike some of his colleagues, and as soon as he’d finished he removed the ‘Black Cap’ traditionally worn during death sentences as a gesture of mourning for the newly-condemned and rushed from the court in tears.

Seddon hadn’t come to hear it. His lawyer didn’t want to hear it and the judge didn’t want to pass it, but there was a percentage of attendees in the public gallery who probably had come to enjoy a genuine life-or-death drama and possibly in the hope of seeing Seddon condemned to hang. They were the trial watchers.

As a pastime, trial watching is nothing new. You might ask what would make people who have no personal or professional connection with a court case bother turning up and cramming the public gallery, but people have been doing so not for decades or centuries, but for millenia. In ancient Rome the Forum was the administrative heart of Roman life where issues were debated, rulings made and laws passed. It also contained the law courts where, in the absence of universally-applied criminal trials there were many private prosecutions. Lawyers held celebrity status in Rome and the public turned out in droves to watch trials, especially those involving unusually gruesome crimes or well-known public figures, as though they were attending the theatre. In a sense, they were, although its performers had faced worse than a bad review if they lost their case. At a time when finely-crafted public executions were the norm, using methods expressly designed to be as hideous as possible, the defendants were in grave danger. A prosecutor losing a case would likely find his forehead branded with the letter K, short for ‘Kalumniator’ or ‘false accuser.’ A defender losing a case might face the same punishment as his client. All in all, the law courts were a great show to attend unless you happened to be performing in it.. If you came merely to watch then you got real drama, not actors playing from a script. You got a taste of tension as the trial was in progress, even more tension as the citizens delivered their verdict and there was always a good chance of seeing either an ecstatic defendant walking free or being clapped in irons and led off to await a gruesome death. And then you could go and watch that as well, if you had the stomach for it. Many Romans usually did.

But it didn’t end there. Trials usually being public affairs, the highest profile cases always attracted increased attendance and still do. The worse the crime or the more famous the defendant, the bigger the crowds flocking into the public gallery. O.J. Simpson, Amanda Knox and Phil Spector all spring to mind.Mafia boss John Gotti may have been the archetypal celebrity gangster, but he wasn’t the only celebrity attending his numerous trials as Hollywood stars Anthony Quinn, Mickey Rourke and Jon Voight all turned up to watch. Some reporters more or less ignored the criminal aspect in favour of endless column inches on which stars had turned up, what they were wearing and why they were there. Gotti himself was the subject of almost daily reports regarding his clothes and hairstyle.

Look through the true crime section in any public library or bookstore or online sotre and you’ll find books devoted to famous trials such as the ‘Notable American Trials’ and ‘Notable British Trials’ collections. Go online and websites like http://www.wildabouttrial.com/ and http://www.websleuths.com/forums/forum.php carry live trial coverage and debate as their most popular content. You don’t have to make an effort to get to court to watch the show, you can do it from your own PC, laptop or mobile device. And many, many people do.

. In the US trial watching has always been a popular pastime. In Britain it still happens, the celebrity of the defendant or witness and/or the gruesome nature of the crime being the yardsticks to measure likely attendance. But, which doesn’t say much for human nature, trial watching in person started losing its popularity after the abolition of the death penalty. After the last British hangings in August 1964 as five-year moratorium was agreed and in 1969 capital punishment for murder was abolished. Curiously, trial watching began to diminish as well.

Nowadays you could put some of that decline down to modern media, especially the internet, making it possible to follow a criminal trial from the comfort of your own home and (reporting restrictions and contempt of court notwithstanding) voice your own opinion from your own armchair. In that they’re not so different from their pre-internet predecessors. The 1920’s through to the 1950’s were what some people think of as the ‘classic’ era of British murders and crime in general, a kind of ‘Golden Age.’ Almost anybody could sit in the public gallery at a murder trial and if it was a high-profile case then there was seldom standing room. At the trials of notorious killers like ‘Doctor’ Crippen, George Smith of ‘Brides in the Bath’ infamy, Herbert Rowse Armstrong (the only British lawyer hanged for murder) and so on. Scheming husbands, jealous lovers, obsessed wistresses, ambitious business partners and suchlike all turned up as defendants, one of the distinguishing features of murder being that it can be committed by almost anybody and for almost any reason. A trial watcher in those days could have the drama of the capital case, they could see the lawyers duel with each other, the witnesses grilled, the defendants under constant strain and experience the heightening tension as the jury delivered their verdict.and, if they were lucky (and in those days they often were) the prisoner was guilty, the judge donned his ‘Black Cap’ and they got to watch them condemned to death as well. It was a vicarious thrill experienced from a safe distance.

People lined up in their hundreds to watch the action and discuss the cases as they unfolded. Even the least-educated, lowest-born trial watcher knew the names of the famous judges and their habitual demeanour. If Justice Avory or Hilbery were presiding then you knew the they would be icily severe, brooking no kind of breach of protocol or levity in their courtroom. Justice Mackinnon or Justice Bucknill, on the other hand, might be inclined to be less hard-nosed. Justice Darling might interject with tart remarks on a regular basis while Justice Shearman might decide (as he so often did) to marry his ironclad Edwardian morality with his judicial duties and sit on the bench glowering mercilessly at anything and anybody that looked they even might be of slightly loose morals. Which, as much as the rather weak and entirely circumstantial evidence, helps explain the highly dubious conviction and execution of Edith Thompson over whose trial Shearman presided. The famous lawyers such as Sir Edward Marshall Hall or Norman Birkett had their admirers and detractors as well. When a well-known defender like Hall was against an equally well-known prosecutor like Hewart or Goddard the anticipated legal battle was touted more like a heavyweight boxing match than a life-or-death criminal trial., The famous detectives of the time, Bob Fabian, Jack Capstick, Fred Cherrill, Ernest Millen, Leonard Burt and others, were public figures whose cases were followed fervently by crime buffs. And the legendary pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury, who made his name convicting Crippen and George Smith (both of whom were hanged) was as much a celebrity as any judge if not more so. Spilsbury carried enough weight simply by turning up that one of his more bitter critics acidly remarked that he could solve a case in days from start to finish, needing only the briefest assistance from the public hangman. High-profile murder trial in those days were as much a theatre of justice as formal criminal proceedings.

Even Britain’s executioners like the Billington family, John Ellis and the Pierrepoint family (especially Albert) attracted a certain fame and notoriety when arriving at a prison to do a job and leaving afterward. Albert Pierrepoint became so well-known that even after he resigned in 1956 (in a dispute over fees, not a matter of conscience) he spent the rest of his life signing into hotels under an assumed name. It seemed as though, British trial watches, now long denied the atavistic thrill of watching somebody tried for the life (and possibly going to watch in the hope of seeing their favourite judge don the dreaded ‘Black Cap’ and recite what was once called ‘the dread sentence’, seemed to lose interest as though trials had a little less spice to them.

It was probably the arrival of the internet that caused a certain resurgence in British trial watching. Looking at the various websites and news coverage, radio programmes, Tv documentaries and so on, it doesn’t look as though we’ve lost our taste for it. If anything, the web has made it possible to make this a global pastime. If I wanted to sit here in Truro and watch a capital murder trial in, say, Florida or Texas, then I could do that.It wouldn’t be the same as being there in person, having attended trials before now I’d certainly notice the difference, but the general principles remain the same.

All of which makes me wonder whether, despite the world having moved on a little in many ways since Roman prosecutors being branded and British judges having long abandoned the ‘Black Cap’ and the ‘dread sentence’, just how much have human beings really changed..?

Leave a Reply